Charles Scott Sherrington facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir

Charles Scott Sherrington

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 43rd President of the Royal Society | |

| In office 1920–1925 |

|

| Preceded by | J. J. Thomson |

| Succeeded by | Ernest Rutherford |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 November 1857 Islington, Middlesex, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Died | 4 March 1952 (aged 94) Eastbourne, Sussex, England, United Kingdom |

| Citizenship | British |

| Alma mater |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Academic advisors | |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Influences |

|

| Influenced |

|

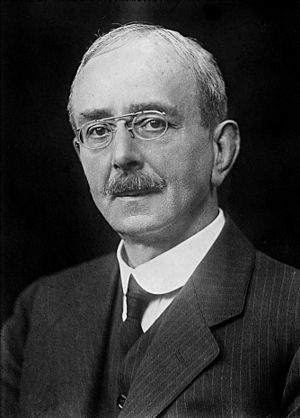

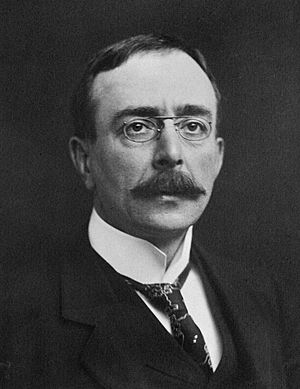

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (27 November 1857 – 4 March 1952) was a very important English scientist. He studied the nervous system, especially how our brains and bodies communicate. This field is called neurophysiology.

Sherrington's experiments helped us understand how our nerves work. He showed that our body's quick reactions, like pulling your hand away from something hot (called a reflex), involve many connected nerve cells, or neurons. He also discovered how signals between neurons can become stronger or weaker.

He even invented the word "synapse" to describe the tiny gap where two neurons connect and pass messages. His famous book, The Integrative Action of the Nervous System (1906), brought all his discoveries together. For this amazing work, he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1932, sharing it with Edgar Adrian.

Besides studying the nervous system, Sherrington also researched other areas like histology (the study of tissues), bacteriology (the study of bacteria), and pathology (the study of diseases). He was also the president of the important Royal Society in the early 1920s.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Learning

Charles Scott Sherrington was born in Islington, London, England, on 27 November 1857. He grew up in a home with Caleb Rose, a respected surgeon in Ipswich. Caleb Rose was a big influence on young Charles. Their home was full of art, books, and interesting collections, which sparked Sherrington's love for learning. He even read a complex book on physiology by Johannes Müller, given to him by Caleb Rose, when he was still young.

Sherrington started at Ipswich School in 1871. There, he was inspired by Thomas Ashe, a famous English poet, who taught him to love classic stories and want to explore the world.

Caleb Rose encouraged Sherrington to study medicine. Sherrington first began his medical training at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. He also studied at St Thomas' Hospital and University of Cambridge. At Cambridge, he chose to focus on physiology, the study of how living things work. He learned from Sir Michael Foster, who was known as the "father of British physiology."

Sherrington was also good at sports! He played football for his school and for Ipswich Town Football Club. He also played rugby for St. Thomas's and was on the rowing team at Oxford. He was a brilliant student at Cambridge, earning top marks in many subjects like botany, anatomy, and physiology. His tutors, Walter Holbrook Gaskell and John Newport Langley, were very interested in how the body's structure relates to its functions.

By 1885, Sherrington had earned his medical degrees from Cambridge.

Important Medical Meeting

In 1881, a big medical meeting called the 7th International Medical Congress took place in London. This is where Sherrington started his work in brain research. During the meeting, there was a big debate. One scientist, Friedrich Goltz, believed that different parts of the brain's outer layer (the cortex) did not have specific jobs. Another scientist, David Ferrier, disagreed, arguing that different brain areas controlled different functions.

A group of scientists, including Sherrington's tutor Langley, was formed to investigate. Sherrington helped examine a dog's brain and later wrote his first scientific paper about their findings in 1884.

Learning from Travels

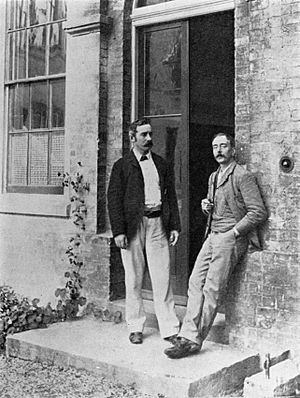

In 1884–1885, Sherrington traveled to Strasbourg to work with Goltz. Sherrington learned a lot from Goltz, saying that he "taught one that in all things only the best is good enough."

Later, in 1885, there was a serious outbreak of cholera in Spain. A Spanish doctor claimed to have a vaccine. Sherrington joined a group of scientists who traveled to Spain to check this claim. They found that the doctor's claim was not true.

Sherrington then went to Berlin to study cholera samples with Rudolf Virchow. Virchow sent him to Robert Koch to learn special techniques. Sherrington ended up staying with Koch for a year, doing research on bacteria. These experiences gave him a strong background in physiology, how living things are shaped, how tissues are structured, and how diseases work. He also visited Italy, where his love for art and rare books grew.

Working Life

In 1891, Sherrington became the superintendent of the Brown Institute in London. This was a research center for studying human and animal bodies and diseases. Here, he studied how nerves connect to the spinal cord and discovered that muscle sensors (muscle spindles) help cause the stretch reflex. The institute allowed him to study many animals, including large apes.

Liverpool University

Sherrington became a full professor at the University of Liverpool in 1895. He stopped his work on diseases and focused on reflexes. He studied animals whose brains had been removed and found that reflexes are not just simple actions of single nerve pathways. Instead, they are complex activities involving the entire body. He also continued his work on "reciprocal innervation," which means that when one muscle group is excited (told to contract), the opposing muscle group is inhibited (told to relax). He explained that stopping an action can be just as active as starting one.

Oxford University

In 1913, Sherrington became a professor at Magdalen College, University of Oxford. He loved teaching bright students there, including Wilder Penfield, who became a famous brain surgeon. Many of his students, like Sir John Eccles, Ragnar Granit, and Howard Florey, went on to win Nobel Prizes themselves.

Sherrington's teaching at Oxford was interrupted by World War I. During the war, he worked long hours in a shell factory to help the war effort. He also used this time to study how people get tired, especially from industrial work. In 1916, he strongly supported allowing women to study medicine at Oxford.

He lived at 9 Chadlington Road in north Oxford for many years. A special plaque was placed on his house in 2022 to honor him.

Later Years

Charles Sherrington retired from Oxford in 1936 and moved back to his childhood town of Ipswich. He built a house there and kept in touch with his former students and other scientists from all over the world. He also continued to enjoy his interests in poetry, history, and philosophy. He was the President of the Ipswich Museum from 1944 until he passed away.

Sherrington remained very sharp mentally until his death at age 94, which was caused by sudden heart failure. Although his body struggled with arthritis in his old age, his mind stayed clear.

Family Life

On 27 August 1891, Sherrington married Ethel Mary Wright. They had one son, Charles E.R. Sherrington, who was born in 1897. During their time at Oxford, they often invited many friends and acquaintances to their home for enjoyable weekend gatherings.

Awards and Recognition

Sherrington received many honors for his important work:

- He became a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1893.

- 1899: Baly Gold Medal from the Royal College of Physicians of London

- 1905: Royal Medal from the Royal Society

- 1922: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire

- 1922–1923: President of the British Science Association

- 1924: Order of Merit

- 1932: Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

By the time he died, Sherrington had received honorary doctorates from twenty-two universities around the world, including Oxford, Paris, Harvard, and Edinburgh.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Charles Scott Sherrington para niños

In Spanish: Charles Scott Sherrington para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |