Malcolm Cowley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Malcolm Cowley

|

|

|---|---|

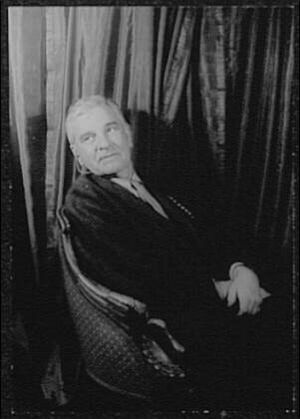

Cowley, photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1963

|

|

| Born | August 24, 1898 Belsano, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | March 27, 1989 (aged 90) New Milford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

|

|

|

Malcolm Cowley (born August 24, 1898 – died March 27, 1989) was an American writer, editor, historian, poet, and literary critic. He is best known for his poetry book Blue Juniata (1929) and his memoir Exile's Return (1934). Cowley was a key figure who wrote about the "Lost Generation" of writers. He was also an important editor and talent scout at Viking Press, helping many famous authors.

Contents

Growing Up and Education

Malcolm Cowley was born on August 24, 1898, in Belsano, Pennsylvania. He grew up in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. His father, William, was a homeopathic doctor.

Cowley went to Shakespeare Street elementary school. In 1915, he graduated from Peabody High School. His friend, Kenneth Burke, also went to school there. Cowley's first published writing appeared in his high school newspaper.

He later attended Harvard University. His studies were paused when he joined the American Field Service during World War I. He drove ambulances and trucks for the French army. He returned to Harvard in 1919 and became editor of The Harvard Advocate. He earned his bachelor's degree in 1920.

Life in Paris: The Lost Generation

In the 1920s, Cowley was one of many American writers and artists who moved to Paris, France. He became well-known for writing about Americans living in Europe. He often spent time with famous writers like Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos. These writers were part of a group known as the "Lost Generation."

In his book Blue Juniata, Cowley described these Americans who traveled abroad after the war. He called them a "wandering, landless, uprooted generation." Hemingway also used the term "lost generation," saying he heard it from Gertrude Stein. This feeling of being "uprooted" made Cowley value artistic freedom. It also shaped his idea of cosmopolitanism, which means being a "citizen of the world," rather than focusing on strong national pride that led to World War I.

Cowley shared his experiences in his memoir, Exile's Return. He wrote that their training made them feel less connected to their home country. It made them feel like "homeless citizens of the world."

While Cowley spent time with many American writers, not everyone admired him back. Hemingway removed a direct mention of Cowley in a later version of his story The Snows of Kilimanjaro. He replaced Cowley's name with a less kind description. John Dos Passos also privately disliked Cowley. However, writers often hid their true feelings to protect their careers, especially after Cowley became an editor at The New Republic.

Despite not selling well at first, Exile's Return was one of the first books to highlight the American expatriate experience. It made Cowley a key voice for the Lost Generation. Literary historian Van Wyck Brooks called it an "irreplaceable literary record" of an important time in American literature.

Early Career and Public Involvement

While in Paris, Cowley was interested in the avant-garde art movement called Dada. Like many thinkers of that time, he was also drawn to Marxism. This idea tried to explain the social and political reasons for the devastating war in Europe. He often traveled between Paris and Greenwich Village in New York. Through these connections, he became close to, but never officially joined, the U.S. Communist Party.

In 1929, Cowley became an associate editor of The New Republic, a magazine with left-leaning views. He helped guide the magazine in a more communist direction. The same year, he translated a French novel from 1913, La Colline Inspirée, by Maurice Barrès. By the early 1930s, Cowley became more involved in radical politics. In 1932, he joined other writers like Edmund Wilson to observe miners' strikes in Kentucky. The mine owners threatened their lives, and one of them was badly beaten. When Exile's Return was first published in 1934, it presented a strong Marxist view of history.

In 1935, Cowley helped create a leftist group called The League of American Writers. Other members included famous writers like Langston Hughes and Lillian Hellman. Cowley became Vice President. Over the next few years, he worked on many campaigns. This included trying to convince the U.S. government to support the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. He resigned from the group in 1940. He was concerned that the organization was too heavily influenced by the Communist Party.

In 1941, as the United States was about to enter World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Cowley's friend, Archibald MacLeish, to lead the Office of Facts and Figures. This office was a early version of the United States Office of War Information. MacLeish hired Cowley as an analyst. This led to anti-communist journalists like Whittaker Chambers publicly criticizing Cowley for his left-wing views.

Cowley soon faced accusations from Congressman Martin Dies and the House Un-American Activities Committee. Dies claimed Cowley belonged to 72 communist groups. This number was likely an exaggeration. MacLeish faced pressure from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to fire Cowley. In January 1942, MacLeish defended Cowley. He told the FBI that they needed to understand that Liberalism was not a crime. Despite this, Cowley resigned two months later. He vowed never to write about politics again.

A Career in Editing and Teaching

In 1944, after stepping away from politics, Cowley began working at Viking Press. He became a literary advisor, editor, and talent scout. He was hired to work on the Portable Library series. This series started in 1943 with books for soldiers. The Portable Library offered cheap paperback reprints. It also highlighted American literature that could be seen as patriotic during wartime. Cowley used this opportunity to promote writers he felt were not getting enough attention.

He first edited The Portable Hemingway (1944). At the time, many thought Ernest Hemingway was a simple writer. Cowley's introduction changed this view. He argued that Hemingway's writing was deep and complex. This new understanding is still common today. Literary critic Mark McGurl says Hemingway's style has become very influential.

The Portable Hemingway sold very well. This allowed Cowley to convince Viking to publish a Portable Faulkner in 1946. William Faulkner was not very well-known at the time. By the 1930s, he was working as a Hollywood screenwriter. His books were in danger of going out of print. Cowley again argued that Faulkner was a very important American writer. He even called him an honorary member of the Lost Generation. Robert Penn Warren called The Portable Faulkner a turning point for Faulkner's fame. Many scholars believe Cowley's essay helped save Faulkner's career. Faulkner won a Nobel Prize in 1949. He later said, "I owe Malcolm Cowley the kind of debt no man could ever repay."

Cowley then published a revised version of Exile's Return in 1951. The new version focused less on Marxist ideas. It emphasized the idea of the "exile's return" as a way to bring a nation together. He wrote about "the old pattern of alienation and reintegration." This time, the book sold much better. Cowley also edited Portable Hawthorne (1948) and a new edition of Leaves of Grass (1959) by Walt Whitman. He also wrote Black Cargoes, A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade (1962) and A Second Flowering (1973).

Starting in the 1950s, Cowley taught creative writing at colleges. Among his students were Larry McMurtry and Ken Kesey. Cowley helped publish Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1962) at Viking. Writing workshops were new at the time. Cowley taught at many universities, including Yale and Stanford. He often moved between teaching and publishing. This allowed him to connect his ideas about being a "citizen of the world" with the academic world.

As a consultant for Viking Press, he pushed for the publication of Jack Kerouac's On the Road. Cowley also helped bring back the fame of F. Scott Fitzgerald. He put together 28 of Fitzgerald's short stories. He also edited a new edition of Tender Is the Night in 1951. His introduction to Sherwood Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio in the early 1960s also helped Anderson's reputation.

Other important works by Cowley include A Second Flowering: Works & Days of the Lost Generation (1973) and And I Worked at the Writer's Trade (1978). And I Worked won a 1980 U.S. National Book Award.

After Cowley's death, The Portable Malcolm Cowley was published in 1990. A reviewer, Michael Rogers, wrote that Cowley was an "unsung hero" of 20th-century American literature. He said Cowley knew everyone and wrote about them with great insight. Rogers also said Cowley's writings on great books were as important as the books themselves.

Cowley remained a kind and supportive person in the world of literature. He wrote to writer Louise Bogan in 1941, saying he didn't want to cause pain to anyone.

Family and Passing

Cowley married artist Peggy Baird; they divorced in 1931. His second wife was Muriel Maurer. They had one son, Robert William Cowley, who is an editor and military historian.

Malcolm Cowley died of a heart attack on March 27, 1989.

Images for kids

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |