Mary Florence Potts facts for kids

Mary Florence Potts (born Webber; November 1, 1850 – June 24, 1922) was an American businesswoman and inventor. She created special clothes irons with handles that could be removed. These irons were shown at big events like the 1876 Philadelphia World's Fair and the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. Her inventions became very popular in North America and Europe during the 20th century. They were known as the most popular heavy metal irons ever made.

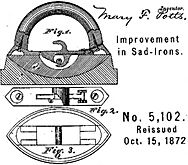

Mary Potts received her first patent for an improved clothes iron when she was just 19. A year later, she patented an even better version. This new design had a wooden handle that could be taken off. The American Machine Company produced and sold her irons as a four-piece set. Her products were sold by famous companies like Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck and Company. These irons continued to be made until 1951.

Contents

Who Was Mary Florence Potts?

Early Life and Family

Mary Florence Potts was born in Ottumwa, Iowa, on November 1, 1850. Her parents were Jacob Hanec Webber and Anna Nancy McGinley, both from Pennsylvania. When she was 17, on June 7, 1868, she married Joseph Hunt Potts in Ottumwa, Iowa. Joseph was 17 years older than her.

Their first child, a son named Oscero, was born in 1869. In 1873, Mary and her family moved from Iowa to Philadelphia. They had a daughter, Leona, born in Philadelphia in 1874. By 1890, the family had moved to Camden, New Jersey. There, her husband and Oscero worked as chemists.

Later Life and Business

Mary's husband passed away in 1901. By 1910, she became a co-owner of the Potts Manufacturing Company with her son, Oscero. This company made optical goods, like lenses. Mary Florence Potts died in Baltimore on June 24, 1922. She was buried at the New Camden Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey.

How Did Mary Potts Improve the Clothes Iron?

Mary Potts is famous for making big improvements to the sadiron. The word "sad" in "sadiron" meant heavy or solid. She started working on these improvements when she was only 19.

The First Patent: A Cooler Handle

In 1870, Mary received her first patent for a unique clothes iron. Her design focused on making ironing easier and more comfortable. Old irons had metal handles that got very hot. Mary replaced these with a cool wooden handle that was much nicer to hold.

Her iron also had a special shape, pointed at both ends. This allowed it to move smoothly in both directions. Instead of solid metal, her iron was hollow. The bottom was thick, but the sides were thin. The hollow part could be filled with materials that didn't transfer heat well, like cement or clay. Since her father was a plasterer, she even tried filling some with a type of plaster of Paris. These materials stopped heat from rising to the user's hand, unlike the old solid metal irons.

The Detachable Handle: A Game Changer

Old metal irons from the 1800s weighed about 5 to 10 pounds. They had to be heated on a stove. They got so hot that people often used a thick cloth mitt or rag to avoid burning their hands. A big problem was that ironing had to stop when the iron cooled down, as it needed to be reheated.

Mary Potts found a clever way to solve this problem. In 1871, she patented a new invention (United States patent #113,448). This design featured a wooden handle that could be detached. It came with three different-sized iron bases. The great thing about Potts's 1871 system was that you could switch out a cooled iron base for a hot one. This meant you could keep ironing without waiting! The different sizes were for different ironing tasks.

The most important part of Potts's iron was its rounded, detachable wooden handle. You could put the iron base on a hot stove to heat it up, but remove the handle. This kept the handle cool and prevented burned fingers. The design of the handle and bases was standard, so they could easily be connected to various sizes of hot bases.

Selling the Innovation

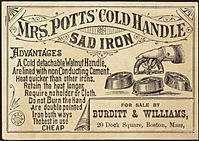

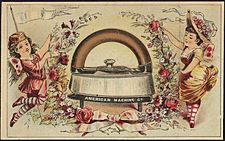

Mary Potts called herself an "inventress," which was a term used back then. At first, she sold her irons herself. Later, the American Machine Company in Philadelphia started making them. The company sold the irons in a kit. This kit included one wooden handle and three iron bases. Since the handle only worked with Potts's bases, it helped sell more irons. The kit also came with a trivet, which is a stand for placing a hot iron on when you're not using it.

In 1894, the Montgomery Ward catalog offered the Potts iron kit for 90 cents. By 1896, it sold for 70 cents. In 1908, you could buy it from the Sears & Roebuck catalog for 78 cents. These special irons were made until 1951.

What Was Mary Potts's Legacy?

Mary Potts's double-pointed clothes iron became a common household item. It was widely used in the 20th century across North America and Europe. Her patented irons were the most popular heavy metal irons ever made.

Her "cold-handled sadiron" was shown at the 1876 Philadelphia World's Fair. Mary traveled all over the United States, giving talks to promote her invention. Her style of irons became so popular that by 1891, special machines were built to make thousands of the wooden handles every day. Her innovative iron was also a favorite at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. The Potts iron system was used worldwide throughout the 20th century, especially in places without electricity.

Mary Potts's idea of a removable handle in 1871 influenced other inventions. For example, Gillette used a similar concept in 1901 for their razors. They created removable and disposable blades that could be swapped for sharper ones. This was like Potts's idea of swapping a cooled iron base for a preheated one. This concept even came before the idea of portable hand tools with removable battery packs that could be swapped for charged ones in the 20th century.