McCants Stewart facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

McCants Stewart

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | July 11, 1877 |

| Died | April 14, 1919 (aged 41) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Tuskegee Institute New York University University of Minnesota Law School |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for | Oregon's first African American lawyer |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Mayme Delia Weir |

| Children | Mary Katherine Stewart |

| Parent(s) | T. McCants Stewart Charlotte L. Harris Stewart |

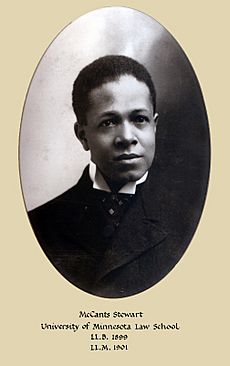

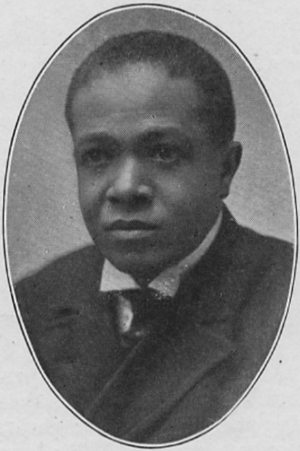

McCants Stewart (July 11, 1877 – April 14, 1919) was an American lawyer. He was born in New York to a well-known attorney. Stewart studied law in Minnesota and later became the first African American lawyer in Oregon.

Even though he worked hard, he didn't find much financial success in Oregon. This led him to move to San Francisco, where he passed away. McCants Stewart lived during a time when "separate but equal" laws were common, meaning Black people were often treated differently. People said his life showed a strong dedication to fairness for all people, especially those who didn't have much power in the northwest.

Contents

McCants Stewart's Life Story

Early Years and Family

McCants Stewart was born in Brooklyn, New York. He was the oldest son of T. McCants Stewart, a famous Black lawyer and civil rights leader. His mother, Charlotte L. Harris Stewart, also went to college. McCants Stewart's father was friends with Booker T. Washington, a well-known educator. His father taught his children important values like working hard and helping themselves.

McCants Stewart's brother, Gilchrist, also became a lawyer. His sister, Carlotta Stewart Lai, helped create Hawaii's public school system. McCants Stewart went to public schools in New York.

Studying at Tuskegee Institute

When he was sixteen, McCants Stewart and his brother went to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1893. This was a Black college that focused on teaching practical skills and self-reliance.

At first, Stewart found it hard to follow the school's strict rules. He sometimes acted out, which made Booker T. Washington unhappy. In July 1894, the school decided to remove him. However, with help from Margaret Murray Washington, he was allowed back in October 1894. Once he returned, he focused on debate, where he became very skilled. He graduated in 1896.

After Tuskegee, Stewart moved to New York and studied law at New York University. He earned a law certificate in 1896 and worked in his father's law office. His father had strict rules for his work, even making him sign a contract.

Life and Law in Minnesota

After a year, Stewart felt tired of the strict rules in his father's office. He moved to Minneapolis, Minnesota, to attend the University of Minnesota Law School. This change helped him become more focused and mature. He did very well in his studies, wrote for the school newspaper, and was active in a literary club. He was also good at debate and was elected secretary of his senior class.

While in law school, Stewart worked as a business manager for two local newspapers, the Twin-City American and the Afro-American Advance. This made him a known person in the Black community.

Fighting Discrimination in Minnesota

During his time in Minnesota, Stewart faced unfair treatment. A restaurant in Minneapolis refused to serve him because he was Black. Other customers saw what happened and gave Stewart their names. He filed a complaint with the Minneapolis City Attorney's Office. This was done under a new state civil rights law passed in 1897.

After an investigation, the city filed the first case under this new law. The restaurant owner was charged with violating Stewart's civil rights. The trial was well-attended. The jury quickly found the owner guilty.

Stewart earned his first law degree (LL.B.) in 1899. He then became a lawyer in the Twin Cities. He continued his studies and in 1901, he became the first African American to receive an advanced law degree (LL.M.) from the University of Minnesota Law School.

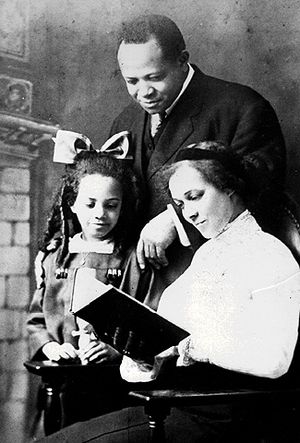

He met his future wife, Mary Delia "Mayme" Weir, in Minneapolis. She was a student at the University of Minnesota. Stewart was known as a great speaker and often gave talks about race issues.

Stewart was active in the Republican Party. In 1902, he was elected Secretary of the Hennepin County Republican Club. However, he started looking for better opportunities out west. By 1904, he decided to move to Portland, Oregon, to practice law. He returned to Minneapolis to marry Mayme on August 22, 1905. Their wedding was a big event in the city's Black community. Their only child, a daughter named Mary Katherine, was born a year later.

Moving to Oregon

McCants Stewart began visiting Oregon in 1903. He was allowed to represent clients in Portland courts even before he passed the state bar exam. He became the first African American to be officially allowed to practice law in Oregon on March 1, 1901.

After opening his office in Portland, Stewart found it hard to earn enough money. The Black population in Oregon was very small, less than 1% of the state's total population until World War II. White people rarely hired Black lawyers, and there weren't many wealthy Black clients either. Stewart also took on Japanese clients. He and his wife did not own property, and he mostly earned money from small legal fees.

Despite financial struggles, Stewart earned the respect of other lawyers. Oregon Supreme Court Justice Henry L. Benson praised his hard work and skill. Stewart was the first African American lawyer to argue a case before the Oregon Supreme Court in 1905. Even though he lost the case, it brought him positive attention.

A Key Civil Rights Victory

The most important moment in his legal career was winning the 1906 civil rights case, Taylor v. Cohn. This case was about Oliver Taylor, a Black train porter, who was told he had to sit in the balcony at a Portland theater. When he found out Black people weren't allowed on the main floor, he refused to use his tickets and sued the owner.

Stewart argued that protecting Black people from unfair treatment was important, even though Oregon didn't have a specific civil rights law at the time. Oregon was more fair than some other western states; its laws didn't separate schools or housing. However, marriage between different races was not allowed.

The state's largest newspaper, The Oregonian, supported the theater owner. It said that Black people should "accept conditions that they cannot change." But Stewart argued that Black people in Oregon had always felt their rights were secure. The first court dismissed the case, but Stewart appealed. The Oregon Supreme Court agreed with Stewart and ruled in favor of Oliver Taylor.

Challenges and Moving On

Winning the case didn't bring Stewart a lot more business, and he continued to struggle financially. He tried investing in companies, but they weren't successful. He also helped start The Advocate, one of Portland's oldest Black newspapers. When his own law office burned down, the newspaper let him use their space.

Stewart faced serious health problems. In 1909, he was in a streetcar accident that badly injured his leg. He had to have his left leg removed below the knee and used a special cork leg. Then, his eyesight started to get worse. These problems made it hard for him, but he kept working to support his family.

In 1911, a Portland Police officer arrested Stewart for simply standing in a restaurant doorway. Stewart believed he had done nothing wrong. The police station refused to charge him. Stewart then filed a complaint against the officer. The complaint was dismissed, but Stewart spoke to the Mayor of Portland and shared his story in The Oregon Journal.

Stewart tried to get a political job, using his many connections in Oregon. He was still a Republican, and members of his party asked for his support. However, because there were so few Black people in Oregon, he didn't get a big political role. He was appointed as a notary public. He also represented Oregon at the 1908 National Negro Fair in Alabama and was appointed to a national committee by President William Howard Taft. In 1916, he tried to change parts of the Oregon constitution that unfairly denied Black people the right to vote and own property, but his effort failed.

Stewart's lack of success in Portland led him to move to San Francisco in 1917. He felt that there simply wasn't enough legal work for him there. He also found it hard to get paid by some clients. His departure meant there were no African American lawyers left in Portland.

Final Years in San Francisco

When Stewart moved to California, he received many letters of praise from important people, including the Governor of Oregon. He arrived in San Francisco feeling hopeful and soon started a law partnership with Oscar Hudson, another respected Black attorney.

A few months later, Stewart had to return to Oregon to finish his last case, Allen v. People's Amusement Co. This case was similar to his earlier victory, Taylor v. Cohn. It involved a Black customer who was not allowed to sit in the white section of a Portland theater. Stewart argued the same points, but this time, the Oregon Supreme Court ruled against him. This meant that after his last case in Oregon, the situation for Black people in public places was no better than when he first arrived.

Back in California, Stewart's hope for San Francisco didn't last long. Even though there were more Black professionals, there wasn't much wealth, and racial separation was even worse than in Portland. His law partnership struggled financially. McCants Stewart passed away on April 14, 1919.

McCants Stewart's Legacy

McCants Stewart achieved several important "firsts" for African Americans. He was the first Black lawyer in Oregon. He was also the first to argue a case and the first to win a case before the Oregon Supreme Court. Additionally, he was the first African American to receive an advanced law degree (LL.M.) from the University of Minnesota Law School.

While Stewart believed in many of Booker T. Washington's ideas about self-reliance, he also actively fought for civil rights for African Americans. This was during a time when unfair treatment was common. Even with his early challenges at Tuskegee, Washington later praised Stewart as a good citizen and a successful graduate.

In 1988, the University of Minnesota Law School created a scholarship in honor of Mary and McCants Stewart. A former dean of the Howard University School of Law said that Stewart "refused to sacrifice his principles" even when facing segregation. The respect he earned from other lawyers and judges shows how smart and strong his character was.

Stewart's daughter, Mary Katherine Stewart-Flippin, later donated her family's important papers to Howard University. These papers included documents from her grandfather, her father, and her husband. She also gave interviews about her family well into the 1980s.

See also

- List of first minority male lawyers and judges in Oregon

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |