Microcosm-macrocosm analogy facts for kids

The microcosm-macrocosm idea is a way of looking at the world. It suggests that there are many similarities between a human being (the microcosm, meaning "small universe") and the entire cosmos (the macrocosm, meaning "great universe"). Because of this idea, people believed that if you understood humans, you could understand the universe, and vice versa.

One cool part of this idea was thinking that the whole universe might be alive. It could even have a mind or a soul, often called the "world soul." This cosmic mind was often seen as divine, like a god. So, people sometimes thought that the human mind or soul was also divine.

Besides thinking about minds and souls, this idea also applied to the human body. For example, the jobs of the seven classical planets were sometimes compared to the jobs of human organs. This included organs like the heart, spleen, liver, and stomach.

This way of thinking is very old. You can find it in many ancient cultures around the world. This includes ancient Mesopotamia, ancient Iran, and ancient China. However, the words "microcosm" and "macrocosm" mostly refer to how this idea grew in ancient Greek philosophy. It then continued through the Middle Ages and the early modern period.

Today, the words microcosm and macrocosm are also used in a simpler way. They can describe any smaller system that represents a larger one. Or, a larger system that is represented by a smaller one.

Contents

History of the Microcosm-Macrocosm Idea

This idea has been around for a very long time. Many thinkers throughout history have explored how humans and the universe might be connected.

Ancient Times

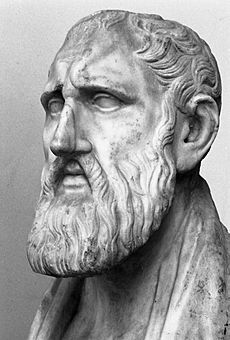

Among ancient Greek and Hellenistic thinkers, several important people believed in the microcosm-macrocosm idea. These included Anaximander (who lived around 610–546 BCE) and Plato (around 428–348 BCE). Also, writers of the Hippocratic Corpus (from the late 400s BCE) and the Stoics (from the 200s BCE) supported it. Later, philosophers who were greatly influenced by Plato and the Stoics also used this idea. These included Philo of Alexandria (around 20 BCE – 50 CE), the authors of the early Greek Hermetica (around 100 BCE – 300 CE), and the Neoplatonists (from the 200s CE).

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, the ideas of Aristotle were very popular. Aristotle believed there was a big difference between the world below the moon (made of four elements) and the world above the moon (made of a fifth element). Even so, many medieval thinkers used the microcosm-macrocosm idea.

Some notable people who adopted it were alchemists like those writing under the name of Jabir ibn Hayyan (around 850–950 CE). Also, the anonymous Shi'ite philosophers known as the Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ ("The Brethren of Purity," around 900–1000 CE) used it. The Andalusian mystic Ibn Arabi (1165–1240) and the German cardinal Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464) also believed in it.

Renaissance Period

The Renaissance saw a renewed interest in Hermeticism and Neoplatonism. Both of these philosophies gave a special place to the microcosm-macrocosm idea. This made the idea much more popular. Some of the most important people who supported this concept during this time include Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486–1535). Others were Francesco Patrizi (1529–1597), Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), and Tommaso Campanella (1568–1639).

The idea was also key to new medical theories from the Swiss physician Paracelsus (1494–1541). His many followers, especially Robert Fludd (1574–1637), also used it.

See also

In Spanish: Microcosmos y macrocosmos para niños

In Spanish: Microcosmos y macrocosmos para niños