Franciscus Patricius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Franciscus Patricius

Franjo Petriš Frane Petrić Francesco Patrizi |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Franciscus Patricius from his book Philosophiae de rerum natura, vol. II, published in Ferrara in 1587

|

|

| Born | 25 April 1529 Cres, Republic of Venice (now Croatia)

|

| Died | 6 February 1597 (aged 67) |

| Era | Early modern philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

|

Main interests

|

|

Franciscus Patricius (Croatian: Franjo Petriš or Frane Petrić, Italian: Francesco Patrizi; 25 April 1529 – 6 February 1597) was a philosopher and scientist from the Republic of Venice. He was born on the island of Cres. He is famous for supporting Platonism and disagreeing with Aristotelianism.

His background is sometimes described as Croatian and sometimes Italian. In Croatia, people usually call him Franjo Petriš or Frane Petrić. His family name on Cres was Petris.

Patricius first studied Aristotle's ideas at the University of Padua. But while he was still a student, he became interested in Platonism. He became a strong opponent of Aristotelianism, writing many detailed works against it.

After many years of struggling to find a steady job, he was invited to work for the House of Este in Duchy of Ferrara in 1577. A special teaching position for Platonic philosophy was created just for him at the University of Ferrara. He became a well-known professor there. He also got into arguments about science and literature.

In 1592, he moved to Rome. The Pope helped him get another new teaching position at the Sapienza University of Rome. In his last years, he had a serious conflict with the Roman Inquisition. They banned his main work, Nova de universis philosophia.

Patricius was one of the last great thinkers of the Renaissance. He had a wide education and worked in many scientific fields. He wanted to create new ideas and was very productive in his writing. He questioned old, accepted ideas and suggested new ways of thinking. For example, he wanted to replace the common Aristotelian natural philosophy with his own model. He also had new ideas about history and poetry.

Even though the church banned some of his work, Patricius's ideas about nature were quite influential. Today, experts recognize his important contributions to the modern concept of space and to the theory of history.

Who Was Franciscus Patricius?

Francesco Patricius came from the town of Cres on the island of the same name. This island was part of the Republic of Venice at that time. Francesco was the son of a priest named Stefano di Niccolò di Antonio Patricius. His family was part of the lower nobility.

Francesco said his family originally came from Bosnia. They had to leave their homeland because of the Turkish conquest. An ancestor named Stefanello came to Cres in the late 1400s.

Patricius followed a common practice of scholars at the time. He used a Latin version of his name, Patricius or Patritius. Since he lived and published his works in Italy, the name Francesco Patricius became well known internationally. In Croatia, people prefer the Croatian forms of his name. The addition "da Cherso" (from Cres) helps tell him apart from another famous scholar named Francesco Patricius from Siena.

His Early Life and Studies

Francesco Patricius was born on April 25, 1529, in Cres. He spent his early childhood there. When he was nine, his uncle, who commanded a Venetian warship, took him on a campaign against the Turks. Francesco was almost captured during the Battle of Preveza in 1538. He spent several years at sea.

In 1543, he went to Venice to learn a trade. His uncle wanted him to go to a business school. But Francesco loved humanism, which is the study of ancient Greek and Roman culture. His father understood this and allowed him to study Latin. Later, his father sent him to study Greek at Ingolstadt University in Bavaria. However, he had to leave Bavaria in 1546 because of a war.

In 1547, Patricius went to Padua, which had one of Europe's best universities. His father wanted him to study medicine, but he didn't like it. When his father died in 1551, he stopped studying medicine. He became more interested in humanistic studies.

He attended philosophy lectures but was disappointed. Padua was a center for Aristotle's ideas, which Patricius strongly disliked. He later called himself "self-taught" because he didn't like the teaching style there. A Franciscan scholar introduced him to Platonism, especially the ideas of Marsilio Ficino. Reading Ficino's works, like Theologia Platonica, was very important for Patricius. He started writing and publishing philosophical works even as a student.

His Career and Challenges

In 1554, Patricius returned to Cres because of a family dispute over his uncle's inheritance. He tried to get a church job there but failed. In 1556, he went to Rome, but he couldn't find work there either. Then he moved to Venice. He tried to get a job at the court in Ferrara but was unsuccessful at first. However, he joined a group of scholars in Venice called the Accademia della Fama.

Working in Cyprus

In 1560, Patricius started working for Giorgio Contarini, a wealthy Venetian. He tutored Contarini in philosophy. Soon, Contarini trusted him and sent him to Cyprus. His job was to check on the family's property there. He improved the land, making it more valuable for growing cotton. But the improvements were expensive, and bad harvests reduced income. Contarini's relatives blamed Patricius. He asked to be released from his job in 1567.

Patricius stayed in Cyprus for a while. He worked for the Catholic Archbishop of Nicosia. But in 1568, with the Turks threatening the island, he left with the archbishop and went back to Venice. He later felt that his years in Cyprus were wasted. However, he did use his time there to find and copy many valuable Greek manuscripts.

Struggles to Make a Living

Back in Venice, Patricius returned to his studies. He went to Padua again, giving private lessons. He also connected with the famous philosopher Bernardino Telesio.

His relationship with the archbishop got worse. He then tried to find work with Diego Hurtado de Mendoza y de la Cerda, a Spanish viceroy and book collector. The viceroy invited him to Barcelona and offered him a good salary. Patricius traveled to Spain, but the financial promise was not kept. He had to return home in 1569.

One good thing from his trip was the idea of selling books. Exporting books from Italy to Barcelona seemed profitable. He started a book shipping business, which worked well at first. But Patricius lacked business skills, and the company failed. In 1570, the Turks captured a shipment of his goods in Cyprus, causing him to lose a lot of money. He got into financial trouble and even had a long legal fight with his former employer, Contarini.

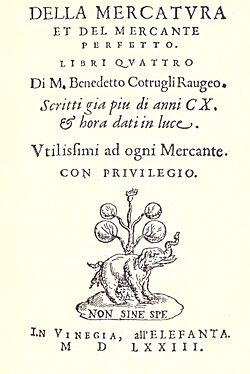

To improve his finances, Patricius got involved in book publishing. In 1571, he helped publish a book about Emblems. But he couldn't meet his agreements because of his money problems. After this, Patricius started his own publishing house, all'Elefanta (meaning "at the Elephant"). He published three books in 1573, but then the business closed.

In 1574, he went to Spain again to sue his old business partners and sell Greek manuscripts. In 1575, he sold 75 ancient books to King Philip II for the royal library. This was a good business deal, but scholars thought of the library as a "book grave" because the books weren't easily available for study. When his legal cases dragged on, Patricius returned home after 13 months.

In 1577, Patricius settled in Modena. He worked for the musician and poet Tarquinia Molza, teaching her Greek.

Professor in Ferrara

In Modena, Patricius finally received the invitation to the court of Ferrara that he had wanted for twenty years. He arrived in Ferrara in late 1577 or early 1578. Duke Alfonso II, D'Este, a great supporter of the arts, welcomed him warmly.

A special teaching position for Platonic philosophy was created for Patricius at the University of Ferrara. He received a good salary, and his financial worries ended. He was highly respected at the court and in the university. He became friends with the Duke and the famous poet Torquato Tasso. During his 14 years in Ferrara, he published many works.

However, Patricius's strong opinions often caused arguments. His criticism of Aristotle led to a written debate with another philosopher. He also got into a literary argument about what makes good poetry.

Professor in Rome and Later Life

Patricius's career reached its peak thanks to Cardinal Ippolito Aldobrandini. The Cardinal invited him to Rome in 1591. In January 1592, Aldobrandini became Pope Clement VIII. The Pope welcomed Patricius warmly when he arrived in Rome in April 1592.

A new teaching position for Platonic philosophy was created for Patricius at the Sapienza University of Rome. He lived in the house of Cinzio Passeri Aldobrandini, the Pope's nephew and a well-known patron of the arts. On May 15, he gave his first lecture on Plato's "Timaios" to a large audience. His salary was the highest at the university, showing the Pope's special favor.

Despite his good relationship with the Pope, Patricius soon faced church censorship. This happened because of his major philosophical work, Nova de universis philosophia, published in Ferrara in 1591. A censor found some statements he thought were against church teachings. For example, Patricius wrote that the Earth rotates, which the censor said went against the Bible.

In October 1592, the church authority for forbidden books, the index congregation, looked into his work. They allowed Patricius to read the censor's report, which was unusual. Patricius wrote a defense letter, saying he would submit but also arguing his points. He tried to explain his ideas and make changes, but it didn't help.

In December 1592, the Congregation decided to list Nova de universis philosophia in the new version of the Index of Forbidden Books. The Jesuit Francisco de Toledo, who was in charge of the censorship, was a strong supporter of Aristotelianism. In July 1594, the Congregation banned the book and ordered all copies destroyed. The book was listed in the updated index in 1596 and in later editions.

Patricius was encouraged to submit a corrected version. He started revising the book, but he died of a fever on February 7, 1597. He was buried in the Roman church Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo, next to Torquato Tasso.

His Important Works

Most of Patricius's writings are in Italian, but some are in Latin. His main Latin works are the Discussiones peripateticae, a long argument against Aristotelianism, and the Nova de universis philosophia, which was his unfinished main work.

Against Aristotle's Ideas

Discussiones peripateticae

Patricius strongly wanted to challenge Aristotelianism. He aimed to disprove not just parts of Aristotle's ideas, but his entire system. He wrote a critical work called Discussiones peripateticae (Peripatetic Examinations). This name refers to the Peripatos, Aristotle's school of philosophy.

He first published a shorter version in 1571. Later, he expanded it into a four-volume work, printed in 1581. This work was a detailed criticism of Aristotle's view of the world.

The first volume includes a biography of Aristotle and a list of his works. It also contains studies to figure out which writings truly belonged to Aristotle. The second volume compares Aristotle's philosophy with older ideas, especially Platonism. Patricius suggested that Aristotle copied or compiled ideas from others. The last two volumes openly criticize Aristotle's ideas, showing them as wrong and a step backward in intellectual history.

Patricius insisted on reading Aristotle's own words directly, not just interpretations by others. He also believed that all of Aristotle's relevant statements should be used, not just one. He saw a decline in philosophy after Aristotle's first students, who still thought independently. Later scholars, like Averroes, made Aristotle's authority absolute, leading to rigid, scholastic Aristotelianism.

New Ideas on Nature and Space

Nova de universis philosophia

Patricius planned his main work, Nova de universis philosophia (New Philosophy of Things in its entirety), to have eight parts. It was meant to explain his complete view of the world. However, he only finished and published the first four parts in 1591. He dedicated the first edition to Pope Gregory XIV, who was his friend since childhood.

In the book's introduction, Patricius suggested that the Pope should change the Catholic school system. He proposed replacing Aristotelianism, which had been dominant, with a better worldview. He listed five models, including his own system, Zoroastrianism, Hermeticism, and Platonism. He said these models were good for religion and acceptable to Catholics, unlike Aristotelianism, which he called godless.

Patricius also criticized the church's use of censorship and the Inquisition to enforce beliefs. He argued that reason and strong arguments were better than force.

The first part of the book, Panaugia (All-Brightness), discusses light as a key force in the universe. The second part, Panarchia (Omnipotence), describes the hierarchical order of the world and its divine source. The third part, Pampsychia (All-souls), presents his idea of a world soul that connects the entire physical cosmos. The fourth part, Pancosmia (All-order), talks about physical cosmology. Patricius believed the universe was infinite.

His Concept of Space

In the 16th century, people usually thought of space as a container that bodies filled. They didn't think of space as something that existed on its own.

Patricius had a new idea about space. He believed space was not a substance or an accident. It was not nothing, but a real "being." He said space was the first thing to exist in the world of the senses. Its existence came before all other physical things. If the world disappeared, space would still exist. He described space as having three dimensions, being able to hold things, and being the same everywhere. He also thought it was like a vacuum, meaning it could be empty.

His Ideas on Cosmology

Aristotelian cosmology said that the material world, enclosed by the sky, was the entire universe. Nothing could exist outside this limited universe, not even time or empty space. Patricius, however, thought that the material world was a limited area surrounded by empty space. He questioned the idea that the material world was spherical. He suggested it might be shaped like a tetrahedron.

He believed the Earth rotated on its axis every day. He didn't think the sky rotated around a fixed Earth because the speed needed would be too great. He also rejected the idea that stars were attached to transparent spheres. Instead, he thought they moved freely in space. He also gave up the idea of Sphere Harmony, which said that the moving spheres created music. However, he still believed in a harmonious structure of the cosmos, like Plato did. When a new star (a supernova) appeared in 1572, he used it to argue that Aristotle's claim that the sky was unchangeable was wrong.

In Patricius's model, the material world is surrounded by an infinitely large, empty space filled with light. This empty space must be bright because there's no matter to create darkness. Space existed before matter was created. He also believed in tiny empty spaces (vacuums) between particles of matter. He saw condensation as proof of these vacuums, as they would be filled during the process.

For Patricius, the creation of the cosmos was not a random act of God, but a necessity. It came from God's nature, which demands creation. God must create. God is the source of everything, which Patricius called un'omnia ("One-Everything").

The first thing created was space. Then came "light," not just physical light, but a principle that creates form and knowledge. From this light came "seeds" of things, which were introduced through "heat" into a "flow" or "moisture." These were not yet material but were the patterns for world things. These four principles—space, light, flowing, and warmth—form the basis of the cosmos. The material world then emerges from them.

This cosmology also meant that nature was not dark or mysterious. It was clear and revealed itself, so humans could understand it.

His View on Time

Patricius criticized Aristotle's definition of time as "the number or measure of movement." He argued that time exists without being measured or counted. He also said Aristotle only considered movement and ignored stillness. Patricius believed that time is simply the duration of a body.

This meant that time was not as important as space. Since time depends on the existence of bodies, and bodies need space, time was secondary to space and bodies.

Ideas on Society and History

The Ideal City

In his early work, La città felice (The happy city), Patricius described an ideal state. He followed Aristotle's ideas but also showed the influence of Platonism.

He believed the goal of human life was to achieve happiness. For Christians, this meant future bliss in heaven. But there also needed to be happiness on Earth, which he linked to practicing virtue. The state, like an ancient polis or Italian city-republic, should create conditions for this happiness. The city's happiness was the sum of its citizens' happiness.

People's basic needs, like good climate, water, and food, had to be met. Then, community life could be improved. Citizens should know each other and interact, perhaps through shared meals. Education and intellectual exchange were important. The city shouldn't be too big. Social inequality should be limited, and public meeting places provided. Patricius also believed that leaders should not hold power for too long, and all citizens should have access to high offices. This would prevent tyranny or rule by a few. Citizens, not hired soldiers, should protect the city.

He thought religious practices and priests were necessary. The religion of the "happy city" was not specifically Christian but involved worshiping "the gods."

Educating children for virtue was a key goal. Children should not be exposed to bad influences. Music and painting education were important for later philosophical study.

Patricius, like Aristotle, believed that only the upper classes, the rulers, had political rights. Farmers, artisans, and traders were too busy working to achieve happiness. Their hard work was necessary for the well-being of the upper class.

Forms of Government

Patricius believed that a balanced republican mixed constitution was the best form of government. This meant combining elements of different types of rule. He thought the Republic of Venice was a good example. In Venice, the Doge represented individual rule, the Senate represented rule by a small elite, and the Grand Council allowed participation from many citizens.

Why Study History?

Patricius was a pioneer in the theory of history. His ten dialogues, Della historia diece dialoghi, published in 1560, discussed the basics of history and how to research it. He believed that studying history was about understanding human efforts to live a "good life" in a social context.

He argued that humans are driven by emotions. Learning to manage these emotions is key to a "good life." This happens through practice in the community. History helps us understand the past of our community. A person who only lives in the present would be controlled by their emotions, like an animal. History helps us learn from the past to deal with social challenges in the present.

Scientific History Research

Patricius believed that historians should only aim to find the historical truth and facts. He thought that judging what happened as good or bad should be done separately, not by the historian. He disagreed with connecting philosophy and history, saying historians should focus on facts and motives, not hidden causes.

He defined the subject of historical research as all documented and remembered processes in the world. He called these "effects," meaning individual concrete realities over time. He said historians should not just collect facts but also find the reasons behind them. This ability to explain historical facts causally made historical research a science.

Patricius believed that history should include everything, not just the actions of kings or generals. He wanted to include natural history, cultural history (intellectual achievements, discoveries, everyday life), and economic history. He said that without understanding a state's economy, its history would be empty. He also called for research into peace, noting that no one had written a history of peace before.

How to Research History

Patricius emphasized clear rules for checking sources. He said not to rely on any authority but to check everything yourself. Even if several authors agree, it might just be a rumor. The best sources were accounts from historians who were involved in the events, but these should be compared with opposing views. He also valued original, unchanged historical records.

He compared a historian's work to peeling an onion, gradually getting to the core of an action. He also used the metaphor of an anatomist, who dissects a body to understand it. The historian must "dissect" an action to find its main actor and reasons.

Patricius even thought it might be possible to write a "history of the future." He believed that if a ruler could accurately predict events, they could record these predictions. This would make a history of the future possible.

Military Ideas

Patricius paid special attention to military matters. He thought it wasn't enough to just report battles. Understanding military organization, structure, weapons, and pay was necessary.

Following Machiavelli, Patricius criticized using foreign hired soldiers. He believed a state should rely on its own citizens and volunteers. He thought it was dangerous to neglect one's own military strength and rely only on alliances or payments for peace. He also believed that fortresses alone could not stop an invasion.

He emphasized the importance of infantry (foot soldiers). He underestimated the power of artillery and early firearms, which made some of his military writings outdated quickly. However, he did recognize the value of guns in naval battles and sieges.

His Ideas on Poetry

Patricius's theory of poetry was different from traditional ideas. He especially disagreed with Aristotle's Poetics. He argued against any rules that limited poetic work, whether in form or content. He opposed the idea that poets should only imitate natural or historical facts.

He believed that poetry could cover anything—divine, human, or natural—as long as it was treated poetically. For him, the only formal definition of poetry was that it had to be in verse.

What Makes Poetry Special?

A key idea in Patricius's poetics was the mirabile, meaning the "wonderful." This is what makes a reader feel astonishment or admiration because it's unusual. He believed the mirabile was the defining quality of poetry.

He saw a connection between humans and poetry. Just as humans connect the spiritual and physical worlds, poetry connects the purely spiritual and the material. The mirabile is like the "spirit" of poetry. It gives the entire poem its quality. This is why verse form is needed, as it's the only form that fits the quality created by the mirabile.

The mirabile not only creates wonder but also helps people learn. It leads them into a world of new and amazing things. Patricius believed that the poet creates a unique reality through their work. The mirabile in poetry comes from a successful mix of the familiar and the unfamiliar. A poet should go beyond what is usually allowed, including the unusual and improbable. By mixing opposites, the poet makes the unbelievable seem believable. This mixing creates the mirabile, turning the text into poetry.

Patricius's broad view of poetry meant he didn't prefer specific role models like Homer or trends like Petrarchism.

He also believed that poetry's goal should not be to just create emotions or deceive. Instead, it should guide the reader's soul through understanding. The mix of familiar and unfamiliar should make the reader want to understand what they don't. This starts a learning process. The mirabile helps poetry teach by encouraging reflection.

Patricius strongly defended the idea of inspiration. He believed that great poets were touched by a higher reality and that their work came from divine inspiration. This inspiration was shown in furore poetico, an ecstatic enthusiasm for poetic creation. He argued against those who said this was just a trick by poets to gain prestige. However, he thought that in his own time, successful poems were products of talent and artistry, not divine inspiration.

His Ideas on Love

Patricius also had new ideas about love, calling it a "new philosophy of love." He built on ancient ideas, especially from Plato. Like Plato, Patricius saw love as a desire for divine beauty, which helps the soul rise to its spiritual home.

He also claimed that love doesn't belong to human nature but comes from outside. He believed that all kinds of love come from self-love, or philautia. This idea was not entirely new, but it was controversial. It was especially provocative to say that Christian love of neighbor and love of God were forms of self-love. In many traditions, self-love was seen as selfish.

However, Patricius didn't mean selfish love. He also included the idea of generosity, where good things are shared. Following Plato, Patricius also gave love a deeper, cosmic meaning. He saw it not just as a human feeling but as a real principle in the universe. On a cosmic level, love connects all parts of the world and ensures that everything continues to exist. It is the foundation of all things.

He believed that God created the universe out of love for himself. God loves things because they are aspects of himself. So, God loves himself in them. Similarly, humans, as images of God, first love themselves. This self-love is necessary for loving others and especially God. For Patricius, every act of love for others is a way of communicating oneself, which means the lover must affirm their own being. Self-love, in this sense, is a manifestation of unity and self-awareness. When an individual's love turns outward, their efforts to preserve themselves extend to the world. Self-love is also the source of all human feelings, thoughts, and actions, including religious ones.

Gallery

See also

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- List of Croats

Editions and translations

Modern editions and translations

- Danilo Aguzzi Barbagli (ed.): Francesco Patricius da Cherso: Della poetica . 3 volumes. Istituto Nazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento, Florence 1969-1971 (also contains the Discorso della diversità de 'furori poetici in the third volume)

- Danilo Aguzzi Barbagli (ed.): Francesco Patricius da Cherso: Lettere ed opuscoli inediti. Istituto Nazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento, Florence 1975 (includes the writings on water management and the dialogue Il Delfino overo Del bacio '. Critical review: Lina Bolzoni:' 'A proposito di una recente edizione di inediti patriziani.' 'In:' 'Rinascimento.' 'Volume 16, 1976, pp. 133–156)

- Lina Bolzoni (ed.): La poesia e le "imagini de 'sognanti" (Una risposta inedita del Patricius al Cremonini). In: Rinascimento. Volume 19, 1979, pp. 171–188 (critical edition of a poetic theory statement by Patricius)

- Lina Bolzoni (ed.): Il "Badoaro" di Francesco Patricius e l'Accademia Veneziana della Fama. In: Giornale storico della letteratura italiana. Volume 18, 1981, pp. 71–101 ( Edition with detailed introduction)

- Silvano Cavazza (ed.): Una lettera inedita di Francesco Patricius da Cherso. In: Centro di Ricerche Storiche - Rovigno: Atti. Volume 9, 1978/1979, pp. 377–396 (Edition a letter from Patricius to the Congregation for the Index with detailed introduction and commentary from the editor)

- Antonio Donato (translator): Italian Renaissance Utopias. Doni, Patricius, and Zuccolo. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham 2019, ISBN: 978-3-030-03610-2, pp. 61–120 (English translation of La città felice )

- Alessandra Fiocca: Francesco Patricius e la questione del Reno nella seconda metà del Cinquecento: tre lettere inedite. In: Patriciusa Castelli (ed.): Francesco Patricius, filosofo platonico nel crepuscolo del Rinascimento. Olschki, Florence 2002, ISBN: 88-222-5156-3, pp. 253–285 (edition of three letters from Patricius from 1580 and 1581 to the Duke of Ferrara)

- Francesco Fiorentino: Bernardino Telesio ossia studi storici su l'idea della natura nel Risorgimento italiano. Volume 2. Successori Le Monnier, Florenz 1874, pp. 375–391 (edition from Patricius's letter to Telesio)

- Sylvie Laurens Aubry (translator): Francesco Patricius: Du baiser. Les Belles Lettres, Paris 2002, ISBN: 2-251-46020-9 (French translation)

- John Charles Nelson (ed.): Francesco Patricius: L'amorosa filosofia . Felice Le Monnier, Florence 1963

- Sandra Plastina (ed.): Tommaso Campanella: La Città del Sole. Francesco Patricius: La città felice. Marietti, Genoa 1996, ISBN: 88-211-6275-3

- Anna Laura Puliafito Bleuel (ed.): Francesco Patricius da Cherso: Nova de universis philosophia. Materiali per un'edizione emendata. Olschki, Florence 1993, ISBN: 88-222-4136-3 (critical edition of Patricius's texts that were created as part of the planned revision of the Nova de universis philosophia )

- Frederick Purnell (ed.): An Addition to Francesco Patricius's Correspondence. In: Rinascimento. Volume 18, 1978, pp. 135–149 (edition of a letter from 1590)

- Thaddä Anselm Rixner, Thaddä Siber (translator): Life and Doctrine of Famous Physicists. Book 4: Franciscus Patritius. Seidel, Sulzbach 1823 ( Translation of excerpts from the Nova de universis philosophia, online)

- Giovanni Rosini (ed.): Parere di Francesco Patricius in difesa di Lodovico Ariosto. In: Giovanni Rosini (ed.): Opere di Torquato Tasso. Volume 10. Capurro, Pisa 1824, p. 159-176

- Hélène Védrine (ed.): Patricius: De spacio physico et mathematico. Vrin, Paris 1996, ISBN: 2-7116-1264-3 (French translation with introduction)

Reprint of early modern issues

- Vladimir Filipović (ed.): Frane Petrić: Deset dijaloga o povijesti. Čakavski Sabor, Pula 1980 ( Della historia diece dialoghi, reprint of the Venice 1560 edition with Croatian translation)

- Zvonko Pandžić (ed.): Franciscus Patricius: Discussiones Peripateticae. Reprint of the four-volume edition Basel 1581 (= Sources and contributions to Croatian cultural history. Volume 9). Böhlau, Cologne u. a. 1999, ISBN: 3-412-13697-2 (with introduction by the editor)

- Anna Laura Puliafito Bleuel (ed.): Francesco Patricius: Della retorica dieci dialoghi. Conte, Lecce 1994, ISBN: 88-85979-04-1 (reprint of the Venice 1562 edition)

16th century editions

- Di M. Francesco Patritio La città felice. Del medesimo Dialogo dell'honore Il Barignano. Del medesimo discorso della diversità de 'furori poetici. Lettura sopra il sonetto del Petrarca La gola e'l sonno e l'ociose piume. Giovanni Griffio, Venice 1553 (online)

- L'Eridano in nuovo verso heroico. Francesco de Rossi da Valenza, Ferrara 1557 (online)

- Le rime di messer Luca Contile, divise in tre parti, con discorsi et argomenti di M. Francesco Patritio et M. Antonio Borghesi. Francesco Sansovino, Venice 1560 (online)

- Della historia diece dialoghi. Andrea Arrivabene, Venice 1560 (online)

- Della retorica dieci dialoghi. Francesco Senese, Venice 1562 (online)

- Discussionum Peripateticarum tomi IV. Pietro Perna, Basel 1581 (online)

- La militia Romana di Polibio, di Tito Livio, e di Dionigi Alicarnaseo. Domenico Mamarelli, Ferrara 1583 (online)

- Apologia contra calumnias Theodori Angelutii eiusque novae sententiae quod metaphysica eadem sint quae physica eversio. Domenico Mamarelli, Ferrara 1584 (online)

- Della nuova Geometria di Franc. Patrici libri XV. Vittorio Baldini, Ferrara 1587 (online)

- Difesa di Francesco Patricius dalle cento accuse dategli dal Signor Iacopo Mazzoni. Vittorio Baldini, Ferrara 1587

- Risposta di Francesco Patricius a due opposizioni fattegli dal Signor Giacopo Mazzoni. Vittorio Baldini, Ferrara 1587

- Philosophiae de rerum natura libri II priores, alter de spacio physico, alter de spacio mathematico. Vittorio Baldini, Ferrara 1587 (online)

- Nova de universis philosophia. Benedetto Mammarelli, Ferrara 1591 (online)

- Paralleli militari. Luigi Zannetti, Rome 1594 (first part of the work; online)

- De paralleli militari. Party II. Guglielmo Facciotto, Rome 1595 (online)

Literature

Overview displays

- Thomas Sören Hoffmann: Philosophy in Italy. An introduction to 20 portraits. Marixverlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN: 978-3-86539-127-8, pp. 293–304

- Paul Oskar Kristeller: Eight philosophers of the Italian Renaissance. Petrarca, Valla, Ficino, Pico, Pomponazzi, Telesio, Patricius, Bruno. VCH, Weinheim 1986, ISBN: 3-527-17505-9, pp. 95–108

- Thomas Leinkauf: Francesco Patricius (1529–1597). In: Paul Richard Blum (ed.): Renaissance philosophers. An introduction. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1999, pp. 173–187

- (in Italian) Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. 1960–2020.

General presentations and studies on several subject areas

- Christiane Haberl: Di scienzia ritratto. Studies on the Italian dialogue literature of the Cinquecento and its epistemological requirements. Ars una, Neuried 2001, ISBN: 3-89391-115-4, pp. 137–214

- Sandra Plastina: Gli alunni di Crono. Mito linguaggio e storia in Francesco Patricius da Cherso (1529-1597). Rubbettino, Soveria Mannelli 1992, ISBN: 88-728-4107-0

- Cesare Vasoli: Francesco Patricius da Cherso. Bulzoni, Rome 1989

Essay collections

- Patriciusa Castelli (ed.): Francesco Patricius, filosofo platonico nel crepuscolo del Rinascimento. Olschki, Florenz 2002, ISBN: 88-222-5156-3

- Tomáš Nejeschleba, Paul Richard Blum (ed.): Francesco Patricius. Philosopher of the Renaissance. Proceedings from The Center for Renaissance Texts Conference [24-26 April 2014]. Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, Olomouc 2014, ISBN: 978-80-244-4428-4 (cz / soubory / publikace / Francesco_Patricius_Conference_Proceedings.pdf online)

Metaphysics and Natural Philosophy

- Luc Deitz: Space, Light, and Soul in Francesco Patricius's Nova de universis philosophia (1591). In: Anthony Grafton, Nancy Siraisi (ed.): Natural particulars. Nature and the Disciplines in Renaissance Europe. MIT Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1999, ISBN: 0-262-07193-2, pp. 139–169

- Kurt Flasch: Battlefields of philosophy. Great controversy from Augustin to Voltaire. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN: 978-3-465-04055-2, pp. 275–291

History and State Theory

- Paola Maria Arcari: Il pensiero politico di Francesco Patricius da Cherso. Zamperini e Lorenzini, Rome 1935

- Franz Lamprecht: On the theory of humanistic historiography. Mensch and history with Francesco Patricius. Artemis, Zurich 1950

Literary Studies

- Lina Bolzoni: L'universo dei poemi possibili. Studi su Francesco Patricius da Cherso. Bulzoni, Rome 1980

- Luc Deitz: Francesco Patricius da Cherso on the Nature of Poetry. In: Luc Deitz u. a. (Ed.): Neo-Latin and the Humanities. Essays in Honor of Charles E. Fantazzi (= Essays and Studies. Volume 32). Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, Toronto 2014, ISBN: 978-0-7727-2158-7, pp. 179–205

- Carolin Hennig: Francesco Patriciuss Della Poetica. Renaissance literary theory between system poetics and metaphysics (= Ars Rhetorica. Volume 25). Lit, Berlin 2016, ISBN: 978-3-643-13279-6

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |