Mud March facts for kids

The Mud March happened from January 20 to January 23, 1863. It was an attempt by Union Army Major General Ambrose Burnside to attack Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. After a big loss at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Burnside wanted to prove himself. He planned for his army to march across the Rappahannock River in winter.

He first planned this for December 30, 1862. But he had not told President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln stopped the plan. Three weeks later, with Lincoln's quiet approval, the army marched south. However, heavy winter rains made the roads almost impossible to use. After four days, the attempt failed.

Why the March Happened

On December 15, 1862, Burnside's Union army left the Battle of Fredericksburg. They went back to Falmouth, Virginia. This battle was a big loss for Burnside and a win for Lee. Lee's army lost about 5,300 soldiers defending Fredericksburg. The Union army lost more than twice that number. Burnside lost about 12,600 Union soldiers. These were soldiers killed, injured, or missing.

The Union army's spirits were very low that winter. People in Washington wanted the army to keep moving toward Richmond. This "On to Richmond" plan had failed many times. Newspapers in the North reported that 75,000 Confederate soldiers had left Lee's army. They had gone to help the North Carolina coast. Burnside wanted to attack Lee while his army was weaker.

Burnside personally looked for the best places for his army to cross the Rappahannock River. By January 15, he was still searching for crossing spots. Confederate soldiers watching from afar saw Burnside near Banks Ford. They wondered what he was planning. Burnside finally chose Banks Ford and U.S. Ford. He sent some troops to Muddy Ford to trick the Confederates. This made them think the main crossing would be there. On the morning of January 20, the army began to move.

The March Through Mud

Burnside gave an order to his troops. It said that the time had come to strike a big blow to the rebellion. He wanted to win a major victory for the country. The plan was for five pontoon bridges to be ready by dawn on January 21. These bridges would let two large groups of soldiers cross the river in four hours.

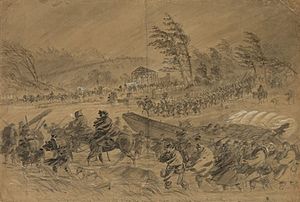

But the night before, it started raining. By the morning of January 21, the roads quickly turned into deep mud. The five pontoon boats and 150 cannons that were supposed to be ready had not arrived. The few pontoon boats that did arrive were not enough to build even one bridge.

- Teams of horses, sometimes double or triple, were hitched to each pontoon wagon.

- In some cases, 150 soldiers tried to help the horses move one boat.

- They could only move a few feet before both horses and men were completely tired.

The rain was part of a big storm that lasted two days. Soldiers and wagons got stuck in mud up to their knees. Burnside kept telling his troops to move forward. But even soldiers carrying only their bags and rifles quickly became exhausted. By this time, Burnside had lost the element of surprise. This gave Lee time to make his defenses stronger. Lee also placed sharpshooters to bother the Union soldiers who managed to get across the river. Confederate soldiers also made fun of Burnside's failure. They put up signs saying "This way to Richmond" and "Burnside's Army Stuck in the Mud"!

The road leading to the river was a complete mess. Wagons, cannons, and men were stuck and could not move. Some mules and horses died right there on the road. They were completely worn out from trying to pull loads they could not move. After three days of this, Burnside decided to try and lift his troops' spirits. He gave them a special drink. This caused some soldiers to argue and fight with each other. Sometimes, whole groups of soldiers were fighting. By the fourth day, January 23, Burnside knew he could not cross the Rappahannock. He finally called off the march.

What Happened Next

Just before the march, Burnside had offered to resign from his job to Lincoln. President Lincoln said no. Burnside, thinking he had Lincoln's support, went back to his command. After the Mud March failed, some of Burnside's top officers criticized him a lot. Burnside then wrote an order to dismiss some generals. He also wrote his resignation again. He then went to Washington.

In a meeting on January 24, Burnside told Lincoln he had to either approve his order or accept his resignation. The President did not approve the order. Instead of letting Burnside resign, he told him to take a break from his duties.

Burnside's order would have fired Generals Joseph Hooker, John Newton, William T. H. Brooks, and John Cochrane. It also would have removed Generals William B. Franklin, William Farrar Smith, and Samuel D. Sturgis from their jobs.

On January 25, 1863, President Lincoln issued a new order. It removed General Burnside from leading the Army of the Potomac. It also removed General Edwin Vose Sumner from his command, as he had asked. General Franklin was also removed. Finally, it gave General Joseph Hooker command of the Army of the Potomac.

That evening, a friend of Burnside's, Henry J. Raymond, met Lincoln. Raymond told the President that Joseph Hooker was not fit to lead the Army. He said there were many things happening in the Army of the Potomac that Lincoln did not know about. He then spoke about General Hooker's very strong comments. Lincoln quietly put his hand on Raymond's shoulder. He said, "This is all true, Hooker does talk badly; but the trouble is stronger with the country to-day than any other man." Raymond then asked what the country would think if they knew this. Lincoln said, "The country would not believe it; they would say it is all a lie." The Army of the Potomac, now led by Hooker, would face the Army of Northern Virginia again in the spring. This next battle was the Battle of Chancellorsville.

Images for kids

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |