Mungo Park (explorer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mungo Park

|

|

|---|---|

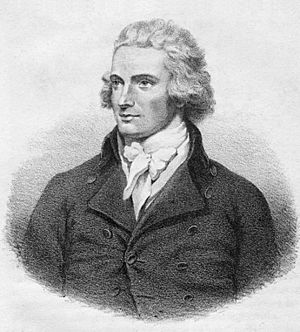

Posthumous portrait (1859) by unknown artist

|

|

| Born | 11 September 1771 Selkirkshire, Scotland

|

| Died | 1806 (aged 35) Bussa, Nigeria

|

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Known for | Exploration of West Africa |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Exploration Surgery |

Mungo Park (born September 11, 1771 – died 1806) was a Scottish explorer. He is famous for his journeys into West Africa. Around 1796, he explored the upper part of the Niger River. He then wrote a very popular book called Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa. In this book, he thought the Niger and Congo rivers were connected, but later explorers found out they were separate.

Mungo Park died during his second trip to Africa. He had traveled about two-thirds of the way down the Niger River. The African Association helped start the "age of African exploration," and Mungo Park was their first successful explorer. He set an example for others who followed. He was the first Westerner to record travels in the central part of the Niger. His book helped people in Europe learn about a large, unexplored continent. This also influenced future European explorers and their plans to set up colonies in Africa.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Mungo Park was born in Selkirkshire, Scotland, on a farm called Foulshiels. He was the seventh of thirteen children. Even though his family were tenant farmers, they were quite well-off. This allowed Mungo to get a good education.

He first studied at home, then went to Selkirk grammar school. When he was 14, he became an apprentice to Thomas Anderson, a surgeon in Selkirk. During this time, Mungo became friends with Anderson's son, Alexander. He also met Anderson's daughter, Allison, who later became his wife.

In October 1788, Park started studying medicine and botany at the University of Edinburgh. He spent a year learning about natural history from Professor John Walker. After finishing his studies, he explored the Scottish Highlands. He did fieldwork on plants with his brother-in-law, James Dickson, who was a botanist.

In 1792, Park finished his medical studies. With help from Joseph Banks, he got a job as an assistant surgeon. He worked on a ship called the Worcester, which belonged to the East India Company. In February 1793, the Worcester sailed to Benkulen in Sumatra.

When he returned in 1794, Park gave a talk to the Linnean Society of London. He described eight new types of fish he found in Sumatra. He also gave Joseph Banks many rare plants from Sumatra.

Exploring the Interior of Africa

First Journey to the Niger River

On September 26, 1794, Mungo Park offered his help to the African Association. This group was looking for someone to find the path of the Niger River. Major Daniel Houghton had tried before but died in the Sahara desert. Sir Joseph Banks supported Park, and he was chosen for the mission.

On May 22, 1795, Park left England on a ship called the Endeavour. It was going to Gambia to trade for beeswax and ivory.

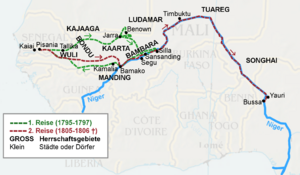

On June 21, 1795, he reached the Gambia River. He traveled about 200 miles (320 km) upriver to a British trading post called Pisania. On December 2, he began his journey into the unknown interior of Africa. He had two local guides with him. He chose a route that went through the upper Senegal basin and the dry region of Kaarta.

His journey was very difficult. In Ludamar, a Moorish chief held him prisoner for four months. On July 1, 1796, he escaped. He was alone with only his horse and a small compass. On July 21, he finally reached the Niger River at Ségou. He was the first European to do so. He followed the river downstream for about 80 miles (130 km) to Silla. He had to turn back there because he didn't have enough supplies to go further.

On his way back, which started on July 29, he took a route further south. He stayed close to the Niger River as far as Bamako. This way, he mapped about 300 miles (480 km) of the river's course. In Kamalia, he became very sick. A kind man took him in, and Mungo lived in his house for seven months. Finally, he reached Pisania again on June 10, 1797. He returned to Scotland on December 22, traveling through Antigua.

People had thought he was dead, so his return with news of the Niger River caused great excitement. His detailed story was published in 1799 as Travels in the Interior of Africa.

His book became a best-seller. It described what he saw, what he went through, and the people he met. His careful descriptions set a new standard for travel writers. They also gave Europeans a look into the human side and complexity of Africa. Park showed them a huge continent that Europeans had not yet explored. After his death, European interest in Africa grew. Park's travels also greatly influenced European plans for colonies in Africa during the 1800s.

Between Journeys

After his first journey, Mungo Park settled at Foulshiels. In August 1799, he married Allison, the daughter of his old teacher, Thomas Anderson. He thought about moving to New South Wales for a job, but it didn't happen. In October 1801, Park moved to Peebles, where he worked as a doctor.

Second Journey to the Niger River

In late 1803, the government asked Mungo Park to lead another trip to the Niger. Park was tired of his quiet life in Peebles, so he accepted. The trip was delayed, and during this time, he practiced his Arabic. His teacher, Sidi Ambak Bubi, was from Mogador (now Essaouira in Morocco).

In May 1804, Park went back to Foulshiels. There, he met Walter Scott, a famous writer who lived nearby. They quickly became friends. In September, Park was called to London to prepare for the new expedition. He left Scott with a hopeful saying: "Freits (omens) follow those that look to them."

By this time, Park believed that the Niger and the Congo rivers were connected. He wrote before leaving Britain: "My hopes of returning by the Congo are not altogether fanciful."

On January 31, 1805, he sailed from Portsmouth for Gambia. He was given the rank of captain to lead the government expedition. Alexander Anderson, his brother-in-law, was his second-in-command. George Scott, another Scottish friend, was the mapmaker. The group also included four or five skilled workers. At Gorée (which was controlled by the British then), Park was joined by Lieutenant Martyn, 35 soldiers, and two sailors.

The expedition started late, right into the rainy season. They didn't reach the Niger until mid-August. By then, only eleven Europeans were still alive. The others had died from fever or dysentery. From Bamako, they traveled to Ségou by canoe. The local ruler, Mansong Diarra, gave them permission to continue. At Sansanding, a little below Ségou, Park got ready for his journey down the unknown part of the river.

With the help of one soldier, Park turned two canoes into one good boat. It was about 40 feet (12 m) long and 6 feet (1.8 m) wide. He named it H.M. schooner Joliba, which was the local name for the Niger River. On November 19, he set sail downstream with the remaining members of his group.

Anderson had died at Sansanding on October 28. Park had lost a very helpful person. Those who went on the Joliba were Park, Martyn, three European soldiers (one was unwell), a guide, and three enslaved people. Before leaving, Park gave letters to Isaaco, a Mandingo guide who had been with him. These letters were to be sent back to Britain from Gambia.

Muslim traders along the Niger did not believe Park was exploring just for knowledge. They thought he was looking for European trading routes and saw him as a threat to their business. They tried to convince Mansong Diarra to kill Park. When Mansong didn't, they tried to influence tribes further down the river. Park understood these dangers. He decided to stay in the middle of the wide river (2 to 3 miles or 3.2 to 4.8 km wide) and attack anyone who came too close. This way, he also avoided paying fees to pass through each kingdom. This made local rulers angry, and they would send messages ahead to warn other tribes about him. Park's approach of using force and avoiding talks with locals made the Europeans seem like enemies. Park was traveling through areas with hostile tribes, partly because of his own actions.

Park wrote to his wife that he planned not to stop or land anywhere until he reached the coast. He expected to arrive around the end of January 1806.

These were the last messages received from Park. Nothing more was heard until news of a disaster reached Gambia.

Death of Mungo Park

Eventually, the British government hired Isaaco to go to the Niger to find out what happened to Park. In Sansanding, Isaaco found Amadi Fatouma, the guide who had gone downstream with Park. Amadi's story was later confirmed by other explorers, Hugh Clapperton and Richard Lander.

Amadi Fatouma said that Park's canoe went down the river to Sibby without problems. After Sibby, three local canoes chased them, but Park's group fought them off with firearms. Similar events happened at Cabbara and Toomboucouton. At Gouroumo, seven canoes chased them. One person in their group died from sickness, leaving "four white men, myself [Amadi], and three slaves." Each person had "15 muskets apiece, well loaded and always ready for action." After passing the king of Goloijigi's home, 60 canoes came after them. They "fought them off after killing many natives." Further on, they met an army from the Poule nation and stayed on the opposite bank to avoid a fight. After a close call with a hippopotamus, they continued past Caffo (where 3 canoes chased them) to an island where Isaaco was captured. Park rescued him, and 20 canoes chased them. This time, they only asked Amadi for small gifts, which Park gave them. At Gourmon, they traded for food and were warned about an ambush ahead. They passed the army, which was "all Moors," and entered Haoussa. They finally arrived at Yauri (which Amadi called Yaour), where Amadi landed. During this long journey of about 1,000 miles (1,600 km), Park had plenty of supplies and stuck to his plan of staying away from the local people. Below Djenné, they passed Timbuktu. At other places, locals came out in canoes and attacked their boat. These attacks were all stopped because Park and his group had many firearms and ammunition, and the locals had none. The boat also avoided many dangers from navigating an unknown river with rapids. Park had built Joliba so it only needed about 1 foot (30 cm) of water.

In Haoussa, Amadi traded with the local chief. Amadi reported that Park gave him five silver rings, some gunpowder, and flints as a gift for the village chief. The next day, Amadi visited the king, who accused Amadi of not giving the chief a present. Amadi was "put in irons." The king then sent an army to Boussa, where the river narrows between high rocks. At the Bussa rapids, not far below Yauri, the boat got stuck on a rock. On the bank, hostile locals gathered. They attacked the group with bows, arrows, and spears. Their situation was hopeless. Park, Martyn, and the two remaining soldiers jumped into the river and drowned. The only survivor was one of the enslaved people. After three months in chains, Amadi was freed and spoke with the surviving enslaved person. From him, Amadi learned the story of the final moments.

What Happened Next

Amadi paid a Peulh man to get Park's sword belt. Amadi then returned to Sansanding and then to Segou. After that, Amadi went to Dacha and told the king what had happened. The king sent an army past "Tombouctou" (Timbuktu) to Sacha. But they decided that Haoussa was too far for a revenge trip. Instead, they went to Massina, a small "Paul" Peulh country. There, they took all the cattle and returned home. Amadi seemed to be part of this trip: "We came altogether back to Sego" (Segou). Amadi then returned to Sansanding through Sego. Eventually, the Peulh man got the sword belt. After an eight-month journey, he met Amadi and gave him the belt. Isaaco met Amadi in Sego, got the sword belt, and returned to Senegal.

Isaaco, and later Richard Lander, found some of Park's belongings, but his journal was never found. In 1827, Park's second son, Thomas, landed on the Guinea coast. He planned to go to Bussa, thinking his father might be held prisoner there. But after going a short distance inland, he died of fever. Park's wife, Allison, received £4,000 from the African Association because of Mungo Park's death. She died in 1840. Mungo Park's body is believed to be buried along the banks of the Niger River in Jebba, Nigeria.

With Park's death, the mystery of the Niger River remained unsolved. Park's idea that the Niger and Congo were the same river became a common belief after he died. However, even when Park was alive, a German geographer named Reichard suggested that the Niger delta was the river's mouth. But his idea was not widely accepted because the delta had so many small streams that it didn't look like it came from a big river. In 1821, James McQueen published a book after 25 years of research. In it, he correctly described the entire course of the Niger. But like Reichard, his ideas didn't get much attention. Several expeditions failed. The mystery was finally solved 25 years after Park's death, in 1830. Richard Lander and his brother were the first Europeans to follow the Niger River from its beginning to the ocean.

Mungo Park's son, Mungo Park (1800-1823), died in India at age 22 while working for the government. He was buried in Trichinopoly.

Awards and Mentions

The Royal Scottish Geographical Society gives out the Mungo Park Medal every year to honor Park.

Mungo Park in Books and Music

- Around 1836, Richard Adams Locke wrote a made-up story called Lost Manuscript of Mungo Park. In it, Park explores the inside of the hollow Earth.

- Mungo Park is mentioned in Herman Melville's 1851 novel Moby-Dick (Chapter 5: Breakfast).

- Mungo Park is one of the two main characters in T. C. Boyle's 1981 historical novel Water Music.

- Tom Fremantle's 2005 travel book The Road to Timbuktu: Down the Niger on the Trail of Mungo Park tells Mungo Park's life story and retraces his journeys.

- Nigerian singer Burna Boy mentions Park in his song "Monsters You Made" from his 2020 album Twice as Tall.

Works by Mungo Park

- Park, Mungo (1797). "Descriptions of eight new fishes from Sumatra. Read 4 November 1794". Transactions of the Linnean Society 3: 33–38. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1797.tb00553.x. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/753896.

- — (1799). Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa: Performed Under the Direction and Patronage of the African Association, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797. London: W. Bulmer and Company. https://archive.org/details/travelsininteri00park/page/n9.

- — (1815). The Journal of a Mission to the Interior of Africa, in the Year 1805: Together with other documents, official and private, relating to the same mission : to which is prefixed an account of the life of Mr. Park: https://archive.org/details/journalofmission00park. London: John Murray. https://archive.org/details/journalofmission00park.

- — (1903). Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa: Performed in the Years 1795, 1796 & 1797, with an Account of a Subsequent Mission to That Country in 1805. London: George Newnes. https://archive.org/details/travelsininterio00park_1.

- — (1816a). Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa: Performed in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797. 1. London: John Murray. https://archive.org/details/travelsininteri02parkgoog.

- — (1816b). Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa: Performed in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797. 2. London: John Murray. https://books.google.com/books?id=89INAAAAQAAJ.

See also

In Spanish: Mungo Park para niños

In Spanish: Mungo Park para niños

- Physician writer