Nazario Collection facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Piedras del Padre Nazario |

|

|---|---|

| Material | Serpentinite |

| Size | Varies |

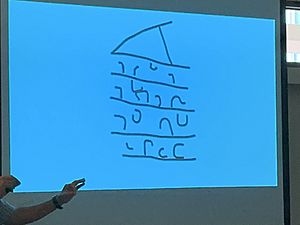

| Writing | 15 to 20 glyphs of unknown origin, separated by lines, with a variance in order and arranged in grids. |

| Created | c. 900 BC – 900 AD |

| Discovered | c. 1870s |

| Present location | Institute of Puerto Rican Culture Museo de Arqueología, Historia y Epigrafía de Guayanilla University of Puerto Rico Smithsonian Institution Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology |

The Nazario Collection is a group of mysterious carved stones. They are also called Father Nazario's Rocks (Spanish: Piedras del Padre Nazario) or Agüeybaná's Library (Spanish: Biblioteca de Agüeybaná). These stones were found in Guayanilla, Puerto Rico.

A Catholic priest, José María Nazario y Cancel, discovered them in the 1800s. The stones are made of local serpentine rock. They have strange carvings, called petroglyphs. For over 130 years, people have wondered if these carvings are linked to ancient civilizations from the Old World (like Europe or Asia).

The stones were hidden underground in a tunnel near Yauco. Father Nazario found so many that he needed help moving them. He brought them to his house to study them. He thought they might be connected to the Ten Lost Tribes from the Bible.

Scientists have debated if the stones are real or fake. Many foreign experts have come to Puerto Rico to study them. An explorer named Alphonse Pinart said they were "undoubtedly authentic." He worried that some people might try to fake stones for money.

After Father Nazario died, most stones went to the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture (ICP). Others are at the University of Puerto Rico and museums in other countries. In the 2010s, archeologist Reniel Rodríguez Ramos led new studies.

Scientists used Radiocarbon dating on soot found on the carvings. This showed the stones are very old, from 900 BC to 900 AD. Geological studies proved the stones and carvings were made in Puerto Rico. High-power microscopes showed the carving technique was different from local native groups. Some carvings look like ancient alphabets from the Canary Islands or Spain. However, a 2019 study found that the way the symbols are arranged is unique. This means they might have been made by a "lost civilization."

Discovering the Ancient Stones

How Father Nazario Found Them

The story of the stones' discovery comes from Catholic priest José María Nazario y Cancel. He was from Sabana Grande but lived in Guayanilla. He had studied ancient languages at the University of Salamanca.

The popular story was told by the priest to historian Adolfo de Hostos. In the late 1870s, Father Nazario was called to a dying woman's bedside. She was a Taíno descendant. She knew Father Nazario liked old artifacts and history.

She decided to tell him where a secret collection of artifacts was hidden. This secret had been passed down in her family for many years. She hoped the priest would protect it. Later, this woman was called "Juana Morales." Some stories said she was the last descendant of Agüeybaná II. He was a famous Taíno leader. These details were not in the first story. There are no records of a "Juana Morales" dying then. But a local Morales family in Barrio Indio has their own stories about the events.

Father Nazario traveled to a river in what is now Barrio Indios. He found a stone slab marking the spot. He dug and found a tunnel. Inside, he found over 800 stones of different sizes. Many looked like human figures. All had strange petroglyphs that didn't match any known native groups in Puerto Rico.

From 1880, the stones were moved to Father Nazario's house in Guayanilla. He kept them with other old pieces he had found. He paid locals to help him move the stones. In 1883, important people like Agustín Stahl visited his house. They talked about starting a Puerto Rico Museum of Natural History.

Early Studies and Questions

Father Nazario called the stones antropoglifitas. This means "human-like carvings." He thought each stone was like a chapter in a big story. He wrote that the stones were found close to Guayanilla. He wondered if they were hidden to protect them during wars between native groups.

The priest was friends with a doctor and writer, Manuel Zeno Gandía. They wrote letters to each other. Father Nazario gave him two stones to keep safe. In 1881, Zeno Gandía went to Spain. He took the stones to Pedro González de Velasco, who started the National Museum of Anthropology.

González de Velasco wanted to keep one stone. They agreed to name it after Nazario and say it was found in Puerto Rico. This caused a small disagreement between Zeno Gandía and the priest. After González de Velasco died, the stone's location became unknown.

The first official mention of the Collection was in 1890 by Alphonse Pinart. He said the discovery was near Yauco. He believed some pieces were "undoubtedly authentic." But he worried that dishonest people might make fake ones for rewards. Pinart also saw similarities between the symbols and ancient alphabets. He took some stones to a museum in Paris. Today, 38 pieces are still there. Nazario later said that other pieces went to Copenhagen and Philadelphia.

In 1893, Nazario wrote about his ideas. He thought the carvings were not from the Taíno or Arawak people. By 1897, he believed they looked like Chaldean or Hebrew languages. He even said he recognized some symbols. Nazario thought the ancient people of Puerto Rico had advanced writing. He wondered if the stones were a kind of ancient national archive.

He tried to translate the symbols using a book about ancient Chaldea. He thought the similarities meant that some of the Ten Lost Tribes traveled from Asia to North America. Then they came to the Caribbean.

Many archeologists did not believe Nazario. They thought he was "imaginative or crazy." They said his ideas meant people came to the New World before Columbus. Some even thought he paid a local jíbaro (countryman) to carve the stones with a machete.

In 1894, Nazario met historian Cayetano Coll y Toste. They talked about deciphering the symbols. But the effort stopped because Nazario would not send the stones to San Juan. During the Spanish–American War, some stones were thrown into a church cistern in Guayanilla. By 1903, Nazario gave talks about the stones, but they did not get much attention.

In 1903, Jesse Walter Fewkes from the Smithsonian Institution visited Puerto Rico. He reportedly offered Nazario $800 for the stones, but Nazario refused. Fewkes wrote that the carvings were "exotic" and not from Native Americans. He thought they might not be ancient.

Fewkes took some pieces with him. He put them in an exhibit with other items of uncertain origin. This made other American archeologists think the stones were fake. They stopped studying them for decades. Local archeologists also lost interest.

In 1905, Nazario showed his writings to a journalist. He talked about his ideas of Old World travelers coming to Puerto Rico. Between 1911 and 1912, Nazario moved to San Juan due to health issues. He had the stones moved there too. In 1908, Nazario wrote that Pinart's visit was in 1880. This helped date the original discovery to the late 1870s. During this time, archeologist Samuel Kirkland Lothrop also visited and took some pieces.

Historian Adolfo de Hostos visited Nazario in San Juan. He heard the now-famous discovery story. Hostos took some pieces. He was not sure if the stones had ancient writing, but he felt they needed more study. When Nazario died in 1919, the stones were separated. About 250 pieces went to a collector and later to the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. The pieces Hostos had went to the University of Puerto Rico. Lothrop's pieces went to the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Public Interest and New Ideas

Bringing the Stones to Light

In 1969, Hostos sent one stone to the British Museum. A scholar named C.B.F. Walker studied it. He said it had features like pieces from 2000 B.C. and might be Sumerian. In the 1980s, Aurelio Tió, a historian, brought attention back to the stones. He said the idea that they were randomly carved with a machete was impossible.

Tió believed that if the stones were real, they would be one of the biggest archeological finds in the Americas. He tried to get major universities and museums to study them again. He wrote over 30 papers about the stones. He also hired a photographer to take high-quality pictures. Linguists from several European countries also got involved. Some thought the stones could be real.

The Phoenician Idea

Some groups, like the Midwestern Epigraphic Society, believed the stones were real. They saw similarities between the symbols and carvings found in Ecuador. Author Barry Fell thought the carvings were not random. He believed they were ancient Greek characters, rearranged to be read in Quechuan, an ancient South American language.

Fell thought ancient Cyprians might have met South Americans. Then they learned Quechuan and wrote it with their alphabet. He believed they later came to Puerto Rico and did the same with the local people. Fell said the Nazario Collection would be the largest discovery related to this culture outside South America. This idea sparked some interest, but conflicting views kept the topic from becoming widely accepted.

Showing the Stones to Everyone

After Aurelio Tió died, others continued to promote the stones. In 2008, interest grew during Guayanilla's 175th anniversary. For the first time, the Collection was publicly displayed. This brought the stones back into the news. The exhibition happened at the Centro Cultural María Arzola.

Guayanilla's government wanted to move the stones there permanently. The next year, they started efforts to create the Museo de Epigrafía Lítica Padre Nazario (Father Nazario Museum of Lithic Epigraphy). This museum would focus on the stones. The museum opened with 19 pieces of the Collection on display.

Modern Scientific Research

Studying the Stones' Makeup

In 2012, Reniel Rodríguez Ramos from the University of Puerto Rico at Utuado began new research. He was worried that most local studies had been done by historians, not archeologists. He found some of the Collection being used for other purposes and the rest in storage at the ICP.

In 2014, Rodríguez took some pieces to the British Museum. He showed them to experts, who agreed that more study was needed. A documentary about the stones also began production.

Most stones show figures in ceremonial poses. They wear headwear and tunics with the carvings. Rodríguez's team also looked at other carvings in the Guánica State Forest. They found some similar headwear in other local artifacts.

Rodríguez could not find the exact place Pinart called "Hanoa, Puerto Rico." So, the team collected samples from the southwestern coast, near Guayanilla and Yauco. They found the stone material was serpentinized peridotite, common in the region.

The research team tried to find as much original information as possible. They found letters between Nazario and Zeno Gandía. Rodríguez concluded that Nazario could not have used the "History of the Nations: Chaldea" book to fake the carvings. This book was published after Pinart's visit.

Scientists from different fields, like geology and physics, helped. They used X-ray diffraction to study the stone's properties. High-power microscopes showed perpendicular scratches, suggesting a specific carving technique. Some pieces show carvings added later.

However, some stones show signs of long-term weathering. This means they were exposed to the elements for a long time. This is not consistent with them being faked in the 1870s and stored indoors. More research is planned with Leiden University.

Carlos Silva from Universidad del Turabo made 3D scans of the pieces. These high-definition images interested philologist Christopher Rollston. Scientists also proposed using thermoluminescence to see when the rocks were last heated. Some pieces have carbon remains that were dated using the C-14 method. This gave a date range of 900 BC to 900 AD.

Confirming Authenticity

In Summer 2019, two independent studies were published. Christopher Rollston concluded that the ancient-looking carvings were not faked by Nazario. He believed they were a form of writing, arranged in lines. But he thought it was a local system, not from across the Atlantic. He said, "these [symbols] are not Mesoamerican writing — they’re not Aztec or Mayan."

Another study on twenty pieces was done at the University of Haifa. It confirmed long-term weathering. It also found that stone tools were used to carve the characters. Traces of gold and red pigment were also found.

New Ideas and Questions

Based on his research, Rodríguez has several ideas. He is studying them without deciding if the stones are real or fake. He thinks some pieces might have been made after the initial discovery. Even if they were all fake, he argues their age makes them archeological artifacts.

Rodríguez noted that religious statues from the Canary Islands have similar postures and faces. These were discovered after Nazario found his stones, so he could not have known about them. Early analysis showed some symbols were similar to the Libyco-Berber alphabet from the Canary Islands.

Rodríguez also found cave paintings near Playa Los Tubos. He sent pictures to a philologist who studies Libyco-Berber characters. She confirmed their nature but lost interest when told they were from Puerto Rico. Rodríguez combined this with studies on how far a drifting boat could travel on the Canary Current. He used this to form a hypothesis he wanted to test.

After the 2019 studies, Rodríguez changed some of his earlier views. He now thinks Nazario's "Ten Lost Tribes" idea is unlikely. The language differences are too great. However, he noted that the way the stones were kept secret was rare, like the Dead Sea Scrolls. He said, "The hands that made these are different from the hands that made [other] artifacts in Puerto Rico."

Rodríguez does not completely rule out ancient inter-continental travel. He stated that these stones "could potentially be the first robust evidence to begin having a discussion about the possibility of pre-nautas (pre-Columbian mariners)." He believes they "question the meta-narrative that Columbus brought writing and history with him." This could push back the known history of Puerto Rico by thousands of years.

Rodríguez is skeptical of Barry Fell's conclusions. He notes that some words Fell translated as Quechuan, like yuca or papaya, are actually from the Arawak language.

|

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |