Ned Christie's War facts for kids

|

|

| Date | 4 May 1887 - 2 November 1892 |

|---|---|

| Location | Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory |

Ned Christie's War is the name given to a long conflict between American lawmen and a respected Cherokee leader named Ned Christie. It started in May 1887. A lawman named Daniel Maples was shot and killed. Ned Christie was accused of this crime. He then ran away to a hidden area in the Cherokee Nation.

For five years, Ned Christie managed to avoid being caught. His friends and family often helped him. But in November 1892, a large group of lawmen finally found him. They attacked his hidden home and killed him.

Contents

The Story of Ned Christie

Who Was Ned Christie?

Before this conflict, Ned Christie was an important person in his community. He was elected to the Cherokee tribal council in 1885. Like his father, Ned was a skilled blacksmith and gunsmith.

Newspapers at the time often called Christie a bandit or outlaw. But there is no proof he committed any crimes before the Maples incident. He was seen as a respected Cherokee leader. He fought to stay alive and protect himself.

The Start of the Conflict

The "war" began in Tahlequah, the capital of the Cherokee Nation. This happened on May 4, 1887. Deputy Daniel Maples was sent to arrest people selling illegal alcohol. Alcohol was not allowed in the Indian Territory. Maples was ambushed and killed outside of town.

A Cherokee man named John Parris was arrested for the murder. He told the police that he saw Ned Christie fire the gun. Ned Christie was in Tahlequah for a council meeting. He said he was innocent.

When Judge Isaac Parker, known as the "Hanging Judge," heard about the killing, he issued an arrest warrant for Christie. He sent a group of lawmen, called a posse, from Fort Smith, Arkansas. This posse was led by Marshal Henry "Heck" Thomas.

Ned Christie did not want to surrender. He knew he might be sentenced to hang in Judge Parker's court. So, he fled to his cabin. It was in a remote wilderness area. This spot was about 15 miles east of Tahlequah. Ned surrounded his home with defenses. He also had people watching for approaching lawmen. This gave him time to prepare or escape.

First Encounters

For almost two years, Ned Christie lived mostly in peace with his friends and family. Marshal Thomas and other lawmen often led posses into the area. But they usually found Ned's house empty. Ned would often sleep at his cabin. But when he heard lawmen were coming, he would hide in the nearby woods.

At this time, the Indian Territory had many outlaws. Newspapers often blamed Christie for various crimes. But he rarely left his hideout. There were some shootouts, but not many people were hurt. All these fights happened at Christie's home.

The first big fight happened on September 26, 1889. Marshal Thomas and his posse finally found Ned's cabin occupied. Ned, his wife, and his son were there. During the gunfight, Ned was badly wounded. His son was shot and killed. One deputy, L.P. Isbel, was also wounded in the shoulder.

Newspaper reports said that the marshals feared Ned's wife had gone for help. They knew Ned had many relatives nearby. They also thought Ned might die in the burning house. So, they took their wounded friend and left. They later learned that Ned was still in the burning building. He was wounded in the head but managed to escape.

Another story says the posse surrounded Ned's shack at dawn. They told him to surrender. But Ned and a friend fired their rifles instead. The marshals then set fire to an outer building. When Ned and his friend ran out for safety, both were wounded by gunfire.

Ned's Fort

Ned eventually built a new home. It was more like a fort than his old cabin. Author Bill O'Neal described it: "After his home and shop were destroyed by a posse in 1889, he [Christie] rebuilt about a mile away on a forbidding cliff that became known as Ned's Fort Mountain. A clear area was made around the two-story fort. The strong walls were two logs thick and lined with oak wood."

It wasn't long before lawmen found this new fort. A newspaper in November 1890 described it. It said Ned Christie was the most famous outlaw in the Territory. Officers learned Ned was about fifteen miles northwest of Tahlequah. They found him with seven other men. These men had built two "fort" houses. They were on a high spot with a good view. From these forts, they could fire at anyone trying to approach. The officers were warned and left quietly. They planned to attack later when they had a better chance.

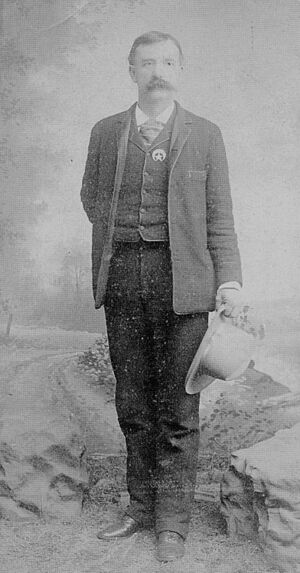

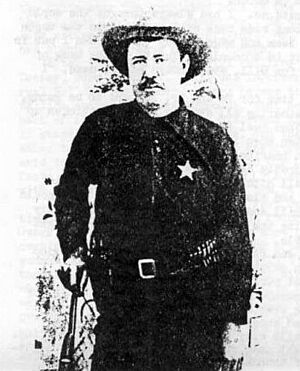

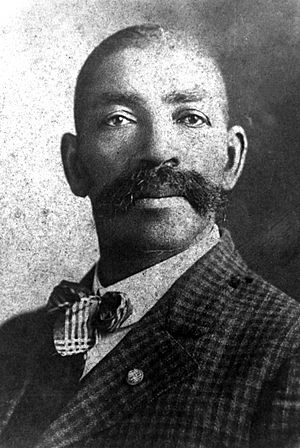

Several shootouts happened between the building of Ned's fort and the end of the conflict in 1892. One important fight happened on November 25, 1890. The government in Washington, D.C. offered a $1,000 reward for Christie, dead or alive. The African-American lawman Bass Reeves took on the challenge. He led an expedition to capture Ned, but it failed.

A newspaper wrote about the attack on November 27, 1890. It said Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves and his posse attacked Ned Christie's home. They burned his stronghold to the ground. They thought Ned had been killed or wounded in the fire. But Christie turned up alive. He was said to be angrier than ever. He vowed revenge on the marshal and his posse.

Some newspapers later reported that Bass Reeves had been killed. Some blamed Ned. Others said it was a trick. Reeves was ambushed over 100 miles from where Christie lived. (In fact, Reeves lived until 1910).

It's not clear if Ned's fort was truly burned down by Reeves. But it was still standing and in use later. On October 11, 1892, another posse attacked the fort. This group included Deputy Marshals Charley Copeland, Milo Creekmore, William Bouden, David Rusk, and D.C. Dye. They were quickly pushed back into the bushes. Two of them were wounded.

The posse then found a wagon. They loaded it with brush to set it on fire. Their plan was to roll the burning wagon towards the house. But the wagon went off course. It rolled into an outbuilding instead. The deputies then decided to use the three sticks of dynamite they had. They threw them one by one. But each stick "bounced harmlessly onto the ground." The posse had to retreat.

The Final Showdown

The final battle to capture or kill Ned Christie began on November 2, 1892. It ended early the next morning. This time, the posse was much larger. It had between sixteen and twenty-five men. They were heavily armed with rifles, dynamite, and a small 3-pounder field gun.

Several men led the posse. These included Deputy Marshals Gideon S. "Cap" White, Gus York, Dick Bruce, Heck Bruner, and Paden Tolbert. Some of these lawmen had been in earlier fights. They knew what to expect.

Christie, Arche Wolfe, and possibly a man named Charley Hare, were inside the fort. They fought off the attackers for over twelve hours. One report says the lawmen fired thirty-eight cannonballs into the fort. They also used over 2,000 rifle rounds. The cannon did not work well. So, the deputies placed dynamite at a certain spot on the wall. They lit the fuse.

The explosion blew a large hole in the wall. It also set the building on fire. Arche Wolfe escaped, but he was caught later. Ned Christie was shot at close range by Deputy Wess Bowman. This happened when Ned charged out of the burning building. Right after that, Sam Maples, the son of the killed Deputy Maples, emptied his revolver into Christie's body.

A newspaper article from The Morning Call described the event. It said Ned Christie was killed on November 4. A posse surrounded his cabin. When one of Christie's friends came out, he was told to surrender. But he fired a shot. Others inside the house also fired. A battle lasted all day without anyone getting hurt. That evening, the officers used dynamite. They blew down part of the cabin and set the rest on fire. While the fire was big, Christie tried to escape. He was told to stop but did not. He was then shot many times. His friend gave himself up. The women of the family were allowed to leave at the start of the fight.

Aftermath

Marshal Tolbert had Christie's body tied to the fort's door. Then, it was loaded into a wagon. It was taken to Fayetteville and then by train to Fort Smith. Along the way, many curious people came to see Christie's body. The door allowed the deputies to prop him up for photographs.

After Fort Smith, Christie's body was sent to Fort Gibson. His family identified him there. He was buried, but his remains were later moved to the Watt Christie Cemetery in Wauhillau, Oklahoma.

Some people believe Ned Christie might have been framed. He was a tribal council member. He was against building railroads through Cherokee land. In 1918, a witness to Daniel Maples' murder came forward. This person cleared Christie's name.

Richard A. "Dick" Humphrey was a former slave. He was adopted into the Cherokee tribe. He was working as a blacksmith in Tahlequah the night Maples was killed. Humphrey told a former deputy marshal and reporter, Fred E. Sutton, what he saw. He said a known badman named Bud Trainor stole Christie's coat. Trainor then used the coat to hide his identity when he murdered Maples. Humphrey had been too afraid to come forward sooner. He feared what Trainor or his friends might do.

Today, Ned Christie is honored with a plaque. It is at the Cherokee Court House in Tahlequah. It says he was "assassinated by U.S. Marshals in 1892." Many of Ned's family members still live in the Cherokee Nation today.

Images for kids