Newton's parakeet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Newton's parakeet |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Life drawing by Paul Jossigny, 1770s | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittaculidae |

| Genus: | Psittacula |

| Species: |

†P. exsul

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Psittacula exsul (Newton, 1872)

|

|

|

|

| Location of Rodrigues | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Newton's parakeet (Psittacula exsul), also called the Rodrigues parakeet, was a type of parrot that is now extinct. It lived only on the island of Rodrigues in the western Indian Ocean. This bird had some unique features that showed it had lived on Rodrigues for a very long time, adapting to its island home. Its closest living relative is the rose-ringed parakeet.

Newton's parakeet was about 40 cm (16 in) long, similar in size to a rose-ringed parakeet. Most of its feathers were greyish or slate blue, which is unusual for Psittacula parrots, as most of them are green. Male parakeets had brighter colors than females and a reddish beak instead of a black one. However, we don't know exactly what a fully grown male looked like because the only male specimen found is thought to be young. Both males and females had a black collar around their neck, but it was clearer on males. Their legs were grey, and their eyes were yellow. Some old reports from the 1600s said that some of these birds were green, which might mean there were both blue and green birds, but we don't have a clear answer for this. We don't know much about how they lived, but they might have eaten nuts from the bois d'olive tree and leaves. They were very friendly and could even copy human speech.

The first time Newton's parakeet was written about was in 1708 by a French traveler named François Leguat. Only a few other people mentioned it after that. The scientific name "exsul" means "exiled," which refers to Leguat, who was exiled from France. We only have two drawings of the bird from when it was alive, both made in the 1770s from a bird kept as a pet. Scientists officially described the species in 1872. The last known bird was collected in 1875, and only two specimens (one male and one female) exist today. The bird became rare because its forests were cut down and maybe because people hunted it. Scientists believe it was finally wiped out by strong cyclones and storms that hit Rodrigues in the late 1800s. People hoped the bird might still be alive until as late as 1967, but there was no proof.

Contents

Discovering Newton's Parakeet

The first person to write about Newton's parakeet was François Leguat in his book A New Voyage to the East Indies in 1708. Leguat was the leader of a group of French refugees who lived on Rodrigues island from 1691 to 1693. Other people who later wrote about the bird were Julien Tafforet in 1726 and the French mathematician Alexandre Pingré in 1761.

In 1871, George Jenner found a female specimen of the bird on Rodrigues. He sent it to Edward Newton, who then sent it to his brother, the bird expert Alfred Newton. Alfred Newton officially described the species in 1872 and named it Palaeornis exsul. The name "exsul" means "exiled" and refers to Leguat, who was exiled from France when he first wrote about the bird. The female specimen is now kept at the Cambridge University Museum.

Alfred Newton wanted to find a male specimen because he thought it would be more colorful. In 1875, William Vandorous shot a male bird, which was then sent to Edward Newton. This male bird is the last one ever recorded and is also kept at the Cambridge Museum. These two specimens are the only preserved Newton's parakeets we have today.

How Newton's Parakeet Evolved

Scientists believe that the Alexandrine parakeet from South Asia might be the ancestor of all Psittacula parrots found on islands in the Indian Ocean. Newton's parakeet had some unique bone features that show it had been isolated on Rodrigues for a very long time. Its bones also show a close link to the Alexandrine parakeet and the rose-ringed parakeet.

Many birds that lived on the Mascarene islands, like the dodo, came from ancestors in South Asia. The British scientist Julian Hume thinks this might be true for all parrots in the area. During the Pleistocene ice age, sea levels were lower, which made it easier for birds to reach some of these islands. Even though we don't know much about most extinct parrots from the Mascarenes, their bones show they had some things in common, like bigger heads and jaws, and stronger leg bones.

A genetic study in 2015 looked at the DNA from the female Newton's parakeet specimen. It found that Newton's parakeet was closely related to a group of rose-ringed parakeet types from Asia and Africa. It separated from them about 3.82 million years ago. The study also suggested that Newton's parakeet might be an ancestor to the parrots of nearby Mauritius and Réunion.

Here's a family tree showing how these parrots are related:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2019, some scientists suggested that the Psittacula group of parrots should be split into smaller groups. They placed Newton's parakeet in a new group called Alexandrinus, along with its closest relatives, the echo parakeet and the rose-ringed parakeet.

What Newton's Parakeet Looked Like

Newton's parakeet was about 40 cm (16 in) long. The male specimen was mostly greyish-blue with a hint of green, and darker on top. Its head was bluer, with a dark line from its eye to its nose area. It had a wide black collar from its chin to the back of its neck. The underside of its tail was grey, its upper beak was dark reddish-brown, and its lower beak was black. Its legs were grey, and its eyes were yellow. The female looked similar but had a greyer head and a black beak. Her black collar was not as clear as the male's.

The bird looked like other Psittacula parrots, especially with its black collar. But its bluish-grey color made it special, as most other parrots in this group are green.

Possible Color Variations

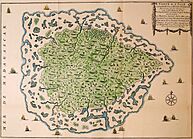

The French scientist Philibert Commerson saw a live Newton's parakeet in the 1770s and described it as "greyish blue." An artist named Paul Philippe Sanguin de Jossigny made two drawings of this bird, which are the only known pictures of Newton's parakeet when it was alive.

Even though the two existing specimens are blue, some old stories from Rodrigues have caused confusion about the bird's color. Leguat wrote:

There are abundance of green and blew Parrets, they are of a midling and equal bigness; when they are young, their Flesh is as good as young Pigeons.

This suggests there might have been both green and blue parrots. Some scientists think the green parrots Leguat mentioned could have been a green version of Newton's parakeet. The feathers of the female specimen actually show both blue and green colors depending on the light.

Scientists have also suggested that some Newton's parakeets might have lacked a pigment called psittacin, which helps make feathers green. If a parrot doesn't have psittacin, its feathers can appear blue. This might explain why the only specimens we have are blue.

Another old account by Tafforet mentioned three kinds of parrots, including one that was "green like the preceding, a little more blue, and above the wings a little red as well as their beak." This might have been a male Newton's parakeet. The related Alexandrine parakeet also has a red patch on its shoulder. The male Newton's parakeet specimen we have might have been too young to have this red patch.

Behavior and Environment

We know very little about how Newton's parakeet behaved, but it was probably similar to other parrots in its group. Leguat said that the parrots on the island ate nuts from the bois d'olive tree. Tafforet also mentioned that parrots ate seeds from the bois de buis shrub. Newton's parakeet might have also eaten leaves, like the echo parakeet does. The fact that it survived for a long time after Rodrigues was heavily deforested suggests it was quite adaptable.

Leguat and his group found the parrots on Rodrigues very tame and easy to catch. They even kept one as a pet and taught it to speak:

Hunting and Fishing were so easie to us, that it took away from the Pleasure. We often delighted ourselves in teaching the Parrots to speak, there being vast numbers of them. We carried one to Maurice Isle [Mauritius], which talk'd French and Flemish.

Scientists have suggested that the echo parakeet from Mauritius could be introduced to Rodrigues to help restore the ecosystem, since it's a close relative of Newton's parakeet. The echo parakeet itself was almost extinct in the 1980s but has since recovered.

Many other animals unique to Rodrigues became extinct after humans arrived. The island's forests were once everywhere but are now mostly gone. Newton's parakeet lived alongside other extinct birds like the Rodrigues solitaire, the Rodrigues parrot, and the Rodrigues rail.

Why Newton's Parakeet Disappeared

Out of about eight parrot species that lived only on the Mascarene islands, only the echo parakeet is still alive. The others likely became extinct because of too much hunting and deforestation (cutting down forests) by humans.

Leguat said that Newton's parakeet was very common when he lived on Rodrigues. It was still common in 1726 when Tafforet visited. But by 1761, when Pingré visited, he noted that the bird was becoming rare. It was still found on small islands near Rodrigues. After this, much of Rodrigues's forests were cut down for farming and raising livestock.

Early visitors often ate Newton's parakeet because they said it tasted good. Since the bird was small, many would have been needed for a single meal. Pingré wrote:

The perruche [Newton's parakeet] seemed to me much more delicate [than the flying-fox]. I would not have missed any game from France if this one had been commoner in Rodrigues; but it begins to become rare. There are even fewer perroquets [Rodrigues parrots], although there were once a big enough quantity according to François Leguat; indeed a little islet south of Rodrigues still retains the name Isle of Parrots [Isle Pierrot].

In 1843, the bird might still have been somewhat common. In 1874, a scientist named Henry H. Slater saw one in southwestern Rodrigues. In 1875, William J. Caldwell saw several. The male bird he collected in 1875 is the last one ever recorded.

A series of strong cyclones hit Rodrigues the next year, in 1876, and might have wiped out the remaining birds. More severe storms hit in 1878 and 1886. Since there were very few forests left by then, there was little cover to protect any birds that remained. So, the male collected in 1875 could have been the very last of its kind.

There were rumors that the bird still existed until the early 1900s, but these were not true. In 1967, an American bird expert, James Greenway, thought a very small group might still be alive on small islands offshore, as these are often the last safe places for endangered birds. However, in 1973, a Mauritian bird expert, France Staub, confirmed that the bird was extinct after visiting Rodrigues.