Rodrigues solitaire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rodrigues solitaire |

|

|---|---|

|

|

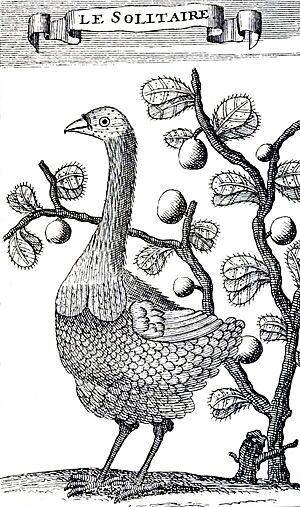

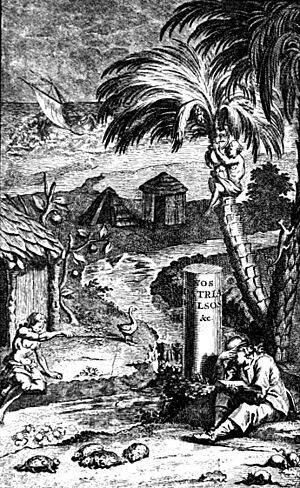

| 1708 drawing by François Leguat, the only known illustration of this species by someone who observed it alive | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Columbiformes |

| Family: | Columbidae |

| Subfamily: | †Raphinae |

| Genus: | †Pezophaps Strickland, 1848 |

| Species: |

†P. solitaria

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Pezophaps solitaria (Gmelin, 1789)

|

|

|

|

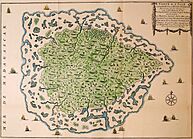

| Location of Rodrigues | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

Didus solitarius Gmelin, 1789

Pezophaps solitarius Strickland, 1848 Didus nazarenus Bartlett, 1851 Pezophaps minor Strickland, 1852 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria) was a large, flightless bird that lived only on the island of Rodrigues. This island is located east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The Rodrigues solitaire was related to pigeons and doves. Its closest relative was the dodo, which also lived on a nearby island called Mauritius. Today, their closest living relative is the Nicobar pigeon.

Rodrigues solitaires were as big as swans. Males were much larger than females. Males could be up to 90 cm (35 inches) tall and weigh 28 kg (62 pounds). Females were smaller, about 70 cm (28 inches) tall and weighing 17 kg (37 pounds). Their feathers were grey and brown, with females being lighter in color. They had a slightly hooked beak and long neck and legs. Both male and female solitaires were very territorial. They had large bony knobs on their wings. These knobs were used for fighting. The Rodrigues solitaire laid only one egg. Both parents took turns sitting on the egg. They ate fruits and seeds, using special gizzard stones to help digest their food.

People first wrote about the Rodrigues solitaire in the 1600s. François Leguat, a French explorer, described it in detail in the late 1600s. The bird was hunted by humans and by animals brought to the island. It became extinct by the late 1700s. For a long time, people only knew about this bird from old writings and drawings. Then, in 1786, some subfossil bones were found. Since then, thousands more bones have been discovered. The Rodrigues solitaire is the only extinct bird that had a constellation named after it, called Turdus Solitarius.

Contents

Naming the Rodrigues Solitaire

The French explorer François Leguat was the first to call this bird the "solitaire." This name means "solitary" because the bird was often seen alone. In 1789, the German scientist Johann Friedrich Gmelin gave the bird its first scientific name, Didus solitarius. He thought it was a type of dodo.

In 1786, some Rodrigues solitaire bones were found in a cave. They were covered in rock formations called stalagmites. These bones were sent to a French scientist named Georges Cuvier. For some reason, he thought they were from Mauritius. This caused some confusion until more bones from Rodrigues were found.

Hugh Edwin Strickland and Alexander Gordon Melville, two English naturalists, suggested in 1848 that the Rodrigues solitaire and the dodo were related. They studied the bones of both birds. Strickland noticed that both birds had similar leg bones, like those of pigeons. He also noted that the Rodrigues solitaire laid only one egg, ate fruits, and took care of its young. These facts supported the idea that they were related. Strickland gave the bird its own genus name, Pezophaps. This name comes from ancient Greek words meaning "pedestrian" (walking) and "pigeon."

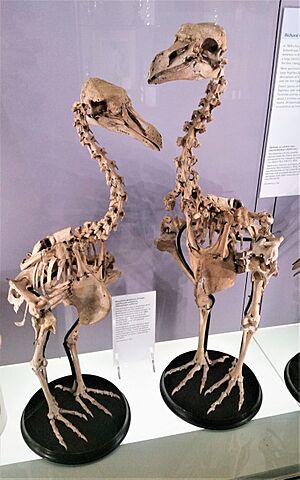

More bones were found in the 1860s and 1870s. English scientists Alfred Newton and Edward Newton studied these bones. They learned a lot about the bird's skeleton. They found that the solitaire was somewhat between a dodo and a regular pigeon. But it had a unique bony knob on its wing. Thousands of bones were found, and scientists even put together full skeletons from different bones.

For many years, the dodo and Rodrigues solitaire were placed in their own separate family. This was because scientists weren't sure how they fit with other pigeons. But later, studies of their bones and DNA analysis showed they were indeed part of the Columbidae family (pigeons and doves). They are now in their own special group called Raphinae.

How the Solitaire Evolved

In 2002, scientists studied the DNA of the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire for the first time. This study confirmed that they were closely related. It also showed they belonged to the pigeon family. The study found that the Nicobar pigeon from Southeast Asia is their closest living relative. After that come the crowned pigeons from New Guinea. The tooth-billed pigeon from Samoa is also a relative. These birds usually live on the ground on islands.

The ancestors of the Rodrigues solitaire and the dodo likely separated a long time ago. The islands where they lived, like Rodrigues and Mauritius, are less than 10 million years old. This means their ancestors could probably fly for a while after they split off. The Nicobar pigeon's ancestors could fly and lived on islands. This suggests that the ancestors of the Rodrigues solitaire and dodo flew from South Asia to the Mascarene Islands.

There were no large mammals on these islands to compete for food. This allowed the solitaire and dodo to grow to very large sizes. They also lost the ability to fly because there were no predators on the islands.

What the Rodrigues Solitaire Looked Like

The Rodrigues solitaire had a slightly hooked beak. Its neck and legs were long. One person who saw it alive said it was the size of a swan. Its head was flat on top, with two bony ridges. A black band was on its head, just behind its beak. The bird's feathers were grey and brown. Females were lighter in color than males.

Males were much bigger than females. They could be 75.7 to 90 cm (30 to 35 inches) tall and weigh up to 28 kg (62 pounds). Females were 63.8 to 70 cm (25 to 28 inches) tall and weighed about 17 kg (37 pounds). Their weight might have changed a lot depending on the season. They were fatter in cool seasons and slimmer in hot seasons.

Both male and female solitaires had a large, bony knob on each wrist. These knobs looked like cauliflower and could have two or three parts. They were about half the length of the wrist bone. Males had larger knobs than females. Some birds did not have these knobs at all, which might mean they were young or didn't have their own territory. In real life, these knobs would have been covered in tough skin. This would have made them look even bigger. Other birds also have similar bony growths on their wings, which they use as weapons.

The Rodrigues solitaire shared some features with the dodo, like its large size. Both birds had thick bones in their pelvis to support their weight. Their wings were small and underdeveloped, showing they couldn't fly. However, their skulls, bodies, and legs changed a lot as they grew.

Old Descriptions of the Bird

We know what the Rodrigues solitaire looked like mostly from a few old descriptions. There are no actual soft body parts left. François Leguat wrote a lot about the bird in his memoirs. He was very impressed by it. He said the males were grey-brown with feet and a beak like a turkey's. He noted they had almost no tail. Their wings were too small for flying. They used their wings to make a rattling noise that could be heard far away. He also mentioned the bony knob on their wings. Leguat said the birds were very fat from March to September and tasted very good.

Leguat also described the female Rodrigues solitaire. He said they were "wonderfully beautiful," some light-colored and some brown. He noted they were very careful to keep their feathers neat. He also mentioned two raised areas on their chest.

Another description came from Julien Tafforet in 1726. He said the solitaire was a large bird, weighing about 40 to 50 pounds. He described their big head with a "frontlet" like black velvet. He also mentioned their short, sharp beak and the "bullet" at the end of their wing. Tafforet confirmed that they did not fly.

Behavior and Life on Rodrigues

Observations from the past show that Rodrigues solitaires were very territorial. They likely fought by hitting each other with their wings. The bony knobs on their wrists helped them do this. Scientists have found broken wing bones, which also suggests they fought. In all birds that have these kinds of knobs or spurs, they are used as weapons.

Besides fighting, both male and female solitaires used their wings to communicate. They could make low-frequency sounds to talk to their mates or warn other birds. This sound could be heard from about 180 meters (200 yards) away. This might have been the size of their territory.

Scientists once thought the bony knobs might be from injuries or a disease. But a 2013 study disagreed. It suggested the knobs grew in response to fighting or hormones. Males who had held a territory for a long time likely had very large knobs. Their mates would also have smaller knobs.

Because of their large size, Rodrigues solitaires probably grew slowly. Some scientists think males could live up to 28 years and females up to 17 years. The birds likely lived mostly in the island's forests.

Many other animals on Rodrigues also became extinct after humans arrived. The island's natural environment was greatly damaged. Forests once covered the whole island. But very little remains today due to trees being cut down. The Rodrigues solitaire lived alongside other extinct birds. These included the Rodrigues rail, parrot, and starling. Extinct reptiles like giant tortoises also lived there.

What the Solitaire Ate

Leguat said the Rodrigues solitaire ate dates. Tafforet mentioned seeds and leaves. It's thought they might have eaten fruits from latan palm trees. We don't know how the young birds were fed. But related pigeons make a special "crop milk" for their babies. The raised areas on the female's chest might have been where this milk was made. If so, the female might have stayed to feed the young. The male would then collect food and bring it back to her.

Several old accounts say the Rodrigues solitaire used gizzard stones. Dodos also did this, which suggests they ate similar foods. Leguat described these stones as brown and about the size of a hen's egg. He said they were rough, flat on one side, and very hard. He believed the birds were born with these stones. But it's more likely that adult birds fed the stones to their young. These stones were even used by people to sharpen knives.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Leguat gave the most detailed account of how the Rodrigues solitaire reproduced. He said they built their nests in clean places. They used palm leaves to make a nest about 45 cm (1.5 feet) high. They only laid one egg, which was much bigger than a goose egg. Both the male and female took turns sitting on the egg. The young bird hatched after seven weeks.

While raising their young, the parents would not let other solitaires come near their nest. If another bird of their species came too close, they would chase it away. The male would call the female, and she would drive away other females. The female would leave other males for the male to chase away. This behavior could last a long time.

After the young bird could take care of itself, the parents would always stay together. They would not separate, even if they mixed with other solitaires. Leguat also observed something unique. A few days after a young bird left the nest, a group of 30 or 40 other young birds would join it. The newly fledged bird, along with its parents, would then go to a quiet place with this group. After that, the old birds would go off alone or in pairs. They would leave the two young birds together, which Leguat called a "marriage."

Tafforet's account also confirms Leguat's descriptions. He added that Rodrigues solitaires would even attack humans who came too close to their chicks. The large size difference between males and females has led some to question if they were truly monogamous. But most other pigeons are monogamous. It's possible that males invited other females into their territories. This might explain why the resident female would act aggressively towards newcomers. The territories likely provided all the food the birds needed. There was probably strong competition for good territories.

Rodrigues Solitaire and Humans

The Dutch first mentioned "dodos" on Rodrigues in 1601. This was likely referring to the Rodrigues solitaire. François Leguat's 1708 book, A New Voyage to the East Indies, was the first to call the bird "solitaire." Leguat was the leader of a group of French refugees. They were stranded on Rodrigues from 1691 to 1693. His book gives the most detailed description of the bird's life and behavior. Leguat's observations are considered some of the first detailed accounts of animal behavior in the wild.

The French refugees liked the taste of the Rodrigues solitaires. They especially enjoyed the young birds. They also used the birds' gizzard stones to sharpen knives. Another detailed description of the bird was found in a document from 1726. It was written by Julien Tafforet, who was also stranded on Rodrigues.

Many old stories say that humans hunted Rodrigues solitaires. Some bones found show signs of being broken by humans. This was likely done to get the bone marrow. In 1735, a French lieutenant described catching and eating two young solitaires. He said they were bigger than turkeys and had a lot of fat. He tried to make a pie, but it was too tough to eat.

Unlike the dodo, no Rodrigues solitaires are known to have been sent to Europe alive.

Why the Solitaire Disappeared

The Rodrigues solitaire likely became extinct between the 1730s and 1760s. The exact date is not known. Its disappearance happened at the same time as a trade in tortoises. Traders would burn plants, hunt solitaires, and bring cats and pigs to the island. These new animals would eat the birds' eggs and chicks.

In 1755, a French engineer tried to find a live solitaire. He was told they still lived in remote parts of the island. He searched for 18 months and offered big rewards, but he couldn't find any. He thought cats were to blame for the birds' decline. But he also suspected that human hunting was the main reason.

When the French astronomer Alexandre Guy Pingré visited Rodrigues in 1761, he didn't see any solitaires. Even though he was told they still existed. To remember his journey, his friend named a constellation after the bird: Turdus Solitarius. The Rodrigues solitaire is the only extinct bird with a constellation named after it. However, mapmakers didn't know what it looked like, so star maps showed other birds.

By the time scientists found bones of the Rodrigues solitaire in 1786, no one living on the island remembered seeing the birds alive. Rodrigues is a small island, only 104 square kilometers (40 square miles). It's unlikely the bird could have survived there without being seen.

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |