Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition facts for kids

The Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition, also known as the Kabul Mission, was a special trip to Afghanistan by Germany and Turkey during World War I (1915–1916). The main goal was to convince Afghanistan to become fully independent from the British Empire. They also wanted Afghanistan to join the war on the side of Germany and Turkey, and attack British India.

This expedition was part of a bigger plan called the Hindu–German Conspiracy. This plan involved efforts by people from India and Germany to start a revolution in India. The mission was officially led by an Indian prince named Raja Mahendra Pratap. German army officers Oskar Niedermayer and Werner Otto von Hentig were the main leaders. Other people involved included Indian nationalists from the Berlin Committee, like Maulavi Barkatullah. Turkey was represented by Kazim Bey, a close friend of Enver Pasha.

Britain saw this expedition as a serious danger. Britain and its ally, the Russian Empire, tried to stop it in Persia in 1915 but failed. Britain also worked secretly, using spies and diplomacy, to keep Afghanistan neutral. Even the Viceroy Lord Hardinge and King George V got involved to make sure Afghanistan stayed out of the war.

The mission did not succeed in getting Afghanistan, led by Emir Habibullah Khan, to join the war. However, it did cause other important events. In Afghanistan, the expedition led to changes and political problems. These problems ended with the Emir being killed in 1919, which then started the Third Anglo-Afghan War. The expedition also influenced Russia's plan to spread socialist revolution in Asia, aiming to overthrow British rule in India. Another result was the creation of the Rowlatt Committee in India. This committee investigated secret plots against British rule, especially those influenced by Germany and Russia. It also changed how Britain dealt with the Indian independence movement after World War I.

Contents

Why the Expedition Happened

During World War I, Germany and Turkey were fighting against Britain and Russia. Germany wanted to weaken its enemies by causing trouble in their colonies, like British India. Germany had already been in touch with Indian nationalists who wanted to end British rule. These groups used countries like Germany, Turkey, and the United States as bases for their anti-British work.

Germany started supporting these Indian nationalists. This effort was led by Max von Oppenheim, who was an archaeologist and historian. He set up the Intelligence Bureau for the East and formed the Berlin Committee. This committee later became the Indian Independence Committee. The Berlin Committee offered money, weapons, and military advice to Indian revolutionaries who were living outside India. They hoped to start a rebellion in India by secretly sending people and weapons.

In Turkey and Persia, nationalist activities had begun earlier. Germany had built strong relationships with Turkey and Persia since the late 1800s. The German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm, even visited Muslim holy sites in 1898 to show support for Islam. Germany spread propaganda, calling the Kaiser "Haji Wilhelm" and saying he had secretly become a Muslim. They wanted to show him as a savior of Islam.

In 1913, a group called the Young Turks took power in Turkey. Even though they were secular, Turkey still had a lot of influence over the Muslim world. The Turkish Sultan was seen as the Caliph, the leader of all Muslims. This was important because millions of people in British India and Afghanistan were Muslim.

When Turkey joined the war, it worked with Germany to target the British and Russian empires, especially in Muslim areas. The Turkish leader, Enver Pasha, had the Sultan declare a jihad (holy war). He hoped this would cause a huge Muslim revolution, especially in India. However, this call for jihad did not have the big effect they hoped for.

At the start of the war, the Emir of Afghanistan declared that his country would stay neutral. The Emir was worried that the Sultan's call for jihad would cause problems among his own people. Afghanistan was officially under British influence, and the Emir received money from Britain. But in reality, Britain had little control over Afghanistan. The British worried that Afghanistan was the only country that could invade India.

First Attempt to Reach Afghanistan

In August 1914, German officials thought about using the pan-Islamic movement to weaken the British Empire and start a revolution in India. They believed an invasion by Afghanistan could cause a revolution in India.

As the war began, unrest grew in India. Some Indian leaders secretly left the country to ask Germany and Turkey for help. A pan-Islamic group in India planned an uprising in the North-West Frontier Province, with help from Afghanistan and Germany.

Enver Pasha planned an expedition to Afghanistan in 1914. He saw it as a Muslim effort led by Turkey, with some German help. The German team included Oskar Niedermayer and Wilhelm Wassmuss. They planned to travel through Persia with Turkish troops and German advisors to Afghanistan. There, they hoped to gather local tribes for jihad.

The Germans tried to reach Turkey by pretending to be a traveling circus. But their equipment and radios were found and taken by Romanian officials. The expedition was eventually canceled. However, Wassmuss left Constantinople to organize tribes in Persia against British interests. While trying to avoid capture, Wassmuss accidentally lost his codebook. When Britain found it, they could read German messages, including the famous Zimmermann Telegram in 1917.

Second Expedition to Kabul

In 1915, a second expedition was organized. This time, the German Foreign Office and Indian leaders from the Berlin Committee were heavily involved. Germany provided weapons and money for the Indian revolutionary plan. Raja Mahendra Pratap, an Indian prince living in exile, was chosen to lead the expedition.

Who Was Part of the Team?

Mahendra Pratap was a prince from India. He had been involved in Indian politics and had traveled the world. He agreed to lead the expedition if the arrangements were made directly with the Kaiser. He even had a private meeting with the Kaiser.

Key German members were Niedermayer and Werner Otto von Hentig. Von Hentig was a Prussian military officer who spoke Persian. Niedermayer was an artillery officer who had traveled in Persia and India before the war. He was in charge of the military side of the expedition as it traveled through the dangerous Persian desert. The team also included German officers Günter Voigt and Kurt Wagner.

Other Indians from the Berlin Committee joined Pratap. These included Champakaraman Pillai and the Islamic scholar Maulavi Barkatullah. Barkatullah had worked with Indian revolutionary groups for a long time. He had even met Nasrullah Khan, the brother of the Afghan Emir, Habibullah Khan.

Pratap also chose six Afghan volunteers from a prisoner of war camp. Two more Germans joined: Dr. Karl Becker, who knew about tropical diseases, and Walter Röhr, a young merchant who spoke Turkish and Persian.

How the Mission Was Set Up

Mahendra Pratap was the official leader, and von Hentig was the Kaiser's representative. He was responsible for the German diplomatic talks with the Emir. To pay for the mission, a large sum of money was put into a bank account in Turkey. The expedition also carried gold and gifts for the Emir, like jeweled watches, fancy pens, and cameras.

The German Ambassador to Turkey was supposed to oversee the mission, but he was sick. So, Prince zu Hohenlohe-Langenburg took over.

The Journey to Afghanistan

To avoid British and Russian spies, the group split up and traveled separately to Constantinople. Pratap and von Hentig started their journey in early 1915, traveling through several European cities to reach Constantinople.

Through Persia

They reached Constantinople on April 17 and waited for three weeks. During this time, Pratap and Hentig met with Enver Pasha and the Sultan. A Turkish officer, Lieutenant Kasim Bey, joined the expedition as the Turkish representative. He carried official letters for the Afghan Emir.

The group, now about twenty people, left Constantinople in early May 1915. They traveled by train and then on horseback through the Taurus Mountains to Baghdad. Since Baghdad had many British spies, the group split up again. Pratap and von Hentig's group left on June 1, 1915, heading towards the Persian border.

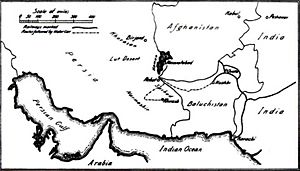

Persia was divided into British and Russian areas, with a neutral zone in the middle. Germany had influence in the central parts of Persia. Local people and religious leaders, who did not like British and Russian influence, supported the mission. The Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, was already getting reports of pro-German feelings among Persian and Afghan tribes. British and Russian forces were actively hunting for the expedition near the Afghan border. The expedition had to be very clever to avoid them in the hot Persian desert.

By early July, the sick members of the group had recovered and rejoined the expedition. They bought camels and water bags. The groups left Isfahan separately on July 3, 1915, to cross the desert. They traveled at night to avoid the extreme heat. Scouts helped them find water and avoid dangerous villages. The group crossed the Persian desert in forty nights. Many people got sick, and some guides tried to leave. On July 23, the group reached Tebbes, where they were welcomed by the town's mayor.

Dodging the British and Russians

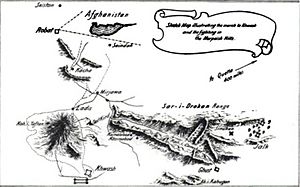

Still 200 miles from Afghanistan, the expedition had to move fast. British and Russian patrols were ahead. By September, the German codebook lost by Wassmuss had been deciphered, making the situation even harder. Niedermayer, now in charge, was a brilliant planner. He sent out three small groups to trick the Russian and British troops, making them think the main group was going in different directions.

Meanwhile, the main group headed towards Birjand, close to the Afghan border. They marched quickly to stay a day ahead of the patrols. Niedermayer learned about the British patrols from nomads. He lost men due to tiredness, leaving the group, or running away. Sometimes, people who ran away would take the group's water and horses.

Birjand was a small town with a Russian consulate, and Niedermayer guessed British forces were also there. He decided to take the northern route, which was very harsh, because his enemies would least expect it. His tricks and false information worked. The British and Russian forces were spread out, looking for what they thought was a large German force. The group now traveled day and night. They covered 255 miles in seven days through the barren desert. On August 19, 1915, the expedition reached the Afghan border. Mahendra Pratap later wrote that only about fifty men were left, less than half of those who started from Isfahan.

Arrival in Afghanistan

After crossing into Afghanistan, the group found fresh water. They marched for two more days and reached Herat. There, they contacted Afghan officials. Von Hentig sent Barkatullah to tell the governor that the expedition had arrived with messages and gifts from the Kaiser for the Emir. The governor sent a grand welcome.

The expedition entered Herat on August 24, welcomed by Turkish troops. They stayed at the Emir's palace. A few days later, the governor officially met them. British agents reported that von Hentig showed the governor the Turkish Sultan's declaration of jihad. He also announced the Kaiser's promise to recognize Afghanistan's independence and offer German help. The Kaiser also promised to give Afghanistan land in Russian Turkestan and India.

The Viceroy of India had already warned the Emir about "German agents." The Emir had promised to arrest the expedition if it reached Afghanistan. However, the expedition members were given freedom in Herat, though they were watched closely. The governor promised to arrange their 400-mile trip to Kabul. On September 7, the group left Herat for Kabul, taking a difficult northern route through the mountains. They spent money and gold to gain popularity with the local people. Finally, on October 2, 1915, the expedition reached Kabul. They were welcomed by the local Turkish community and Afghan troops.

Meetings in Afghanistan

In Kabul, the group stayed as guests at the Emir's palace. But they soon realized they were mostly confined. Guards were around the palace, supposedly for their safety, and armed guides escorted them. For nearly three weeks, Emir Habibullah did not meet them. He used this time to learn about the expedition members and talk with British officials in New Delhi. Meetings only began after Niedermayer and von Hentig threatened to go on a hunger strike.

The Emir's brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, was a religious man. Unlike the Emir, he spoke the local language and was more pro-German. Nasrullah's views were shared by his nephew, Amanullah Khan, the Emir's youngest son. The mission hoped for more support from Nasrullah and Amanullah than from the Emir.

Meeting Emir Habibullah

On October 26, 1915, the Emir finally met them at his palace. He was surprised that such an important task was given to such young men. Von Hentig had to convince the Emir that they were not merchants but brought messages from the Kaiser and the Ottoman Sultan. They wanted to recognize Afghanistan's full independence. The Kaiser's letter, which was typewritten, made the Emir suspicious about its authenticity.

Von Hentig then invited the Emir to join the war on the side of Germany and Turkey. Kasim Bey explained the Ottoman Sultan's declaration of jihad. Barkatullah and Mahendra Pratap urged Habibullah to declare war against the British Empire and help India's Muslims. They suggested that German and Turkish forces could cross Afghanistan towards India, and the Emir could join them. They also pointed out the land gains the Emir could get by joining.

The Emir's reply was smart. He noted Afghanistan's weak position between Russia and Britain. He also mentioned the difficulty of Germany and Turkey sending help to Afghanistan, especially with British and Russian forces in Persia. He was also financially dependent on British money. The mission members could not immediately answer his questions about military and financial help. They only had the authority to ask him to join a holy war, not to promise anything. However, the first meeting was friendly, and the mission hoped for success.

This first meeting was followed by more discussions in October 1915. The message was always the same: join the Central Powers. The expedition members hoped that if Persia joined Germany, it would convince the Emir. Niedermayer argued that Germany would win the war soon. He warned that Afghanistan would be in a bad position if it stayed allied with Britain. The Emir met with the Indian and German delegates separately, promising to think about their ideas but never fully committing. He wanted clear proof that Germany and Turkey could provide military and financial help.

Meetings with Nasrullah

While the Emir hesitated, the mission found more support from his brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, and his younger son, Amanullah Khan. Nasrullah Khan secretly encouraged the mission. Amanullah Khan also gave the group reasons to feel hopeful. However, messages from von Hentig, intercepted by British and Russian spies, reached Emir Habibullah. These messages suggested that von Hentig was ready to cause "internal problems" in Afghanistan if needed to get them to join the war. This worried Habibullah. He started to discourage expedition members from meeting his sons without him present.

During the months the expedition stayed in Kabul, Habibullah avoided committing to the war. He waited to see how the war would turn out. He told the mission he sympathized with Germany and Turkey. He said he would lead an army into India if German and Turkish troops could offer support. When the mission hinted they might leave, he flattered them and invited them to stay.

Meanwhile, expedition members were allowed to move freely in Kabul. They spent money on local goods, which made them popular. Niedermayer even recruited Austrian prisoners of war who had escaped from Russian camps to build a hospital. Kasim Bey met with the local Turkish community, spreading Enver Pasha's message of unity. Habibullah also allowed his newspaper, Siraj al Akhbar, to publish anti-British and pro-German articles. By May 1916, the tone in the paper was so strong that British India started stopping copies meant for India.

New Government and Treaty

In December 1915, the Indian members decided to take a political step. They believed this would convince the Emir to declare jihad, or force his hand. On December 1, 1915, the Provisional Government of India was formed at Habibullah's palace. This was a revolutionary government-in-exile that would take over an independent India. Mahendra Pratap was named president, and Barkatullah was prime minister. They sought support from Russia and China. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, Pratap's government talked with the new Russian government to get their support.

December 1915 also saw progress on the mission's main goal. The Emir told von Hentig he was ready to discuss a treaty of friendship between Afghanistan and Germany. The final draft of the treaty, presented on January 24, 1916, included clauses recognizing Afghan independence and establishing diplomatic relations. It also promised German help against Russia and Britain if Afghanistan joined the war. Germany would provide weapons and money, and maintain a supply route through Persia. The Emir would also be paid £1,000,000. Both von Hentig and Niedermayer signed this document. Niedermayer believed the Emir would start his campaign in April if Germany could provide 20,000 troops and more supplies.

End of the Mission

In the end, Emir Habibullah went back to his hesitant ways. He knew the mission had support within his government and had excited his people. Four days after the treaty was signed, Habibullah called a big meeting. Everyone expected him to declare a holy war. Instead, Habibullah said Afghanistan would remain neutral. He explained that the war's outcome was still unclear, and he wanted national unity. Throughout the spring of 1916, he kept avoiding the mission's requests. He demanded that India rise in revolution before he would start his campaign. It was clear to Habibullah that the treaty would only be valuable if the Kaiser signed it, and if Germany was winning the war.

Meanwhile, Habibullah received worrying British reports that he might be killed or face a coup. His tribesmen were unhappy that he seemed to be too close to the British. His own family and advisors openly doubted his inactivity. Habibullah began removing officials who were close to Nasrullah and Amanullah. He also called back his envoys who had gone to Persia to talk with Germany and Turkey for military aid.

The war also started going badly for Germany and Turkey. The Arab revolt against Turkey and Russia's capture of Erzurum ended hopes of sending Turkish troops to Afghanistan. German influence in Persia also quickly declined. The mission realized that the Emir deeply mistrusted them. A final offer was made by Nasrullah in May 1916 to remove Habibullah from power and lead the tribes against British India. However, von Hentig knew it would not work, and the Germans left Kabul on May 21, 1916. Niedermayer told Wagner to stay in Herat as a contact person. The Indian members also stayed, continuing their efforts for an alliance.

The expedition members knew that once they left the Emir's lands, British and Russian forces, as well as robbers in Persia, would chase them. The group split into several smaller groups, each trying to get back to Germany. Niedermayer headed west through Persia, while von Hentig went over the Pamir Mountains towards Chinese Central Asia. Von Hentig eventually escaped through Chinese Turkestan and the Gobi Desert, reaching Shanghai. From there, he secretly traveled on an American ship to Honolulu. He finally reached Berlin on June 9, 1917. Niedermayer also escaped through Russian Turkestan. He was robbed and left for dead but eventually reached Tehran on July 20, 1916.

Mahendra Pratap tried to get an alliance with Tsar Nicholas II from February 1916, but his messages were ignored. After the Russian Revolution, Pratap's government talked more closely with the new Russian government. In 1918, Mahendra Pratap met Trotsky in Petrograd and urged him to mobilize against British India.

British Counter Efforts

The Seistan Force

The Seistan Force was a group of British Indian Army troops set up in Persia. Their job was to stop Germans from entering Afghanistan and protect British supply routes. A similar Russian force was set up to prevent infiltration into north-west Afghanistan. From March 1916, the force was renamed the Seistan Force. Its task was to "intercept, capture or destroy any German parties attempting to enter Sistan or Afghanistan." They also set up a spy system. After the Russian Revolution, the Seistan Force became the main way for the British to communicate in the region. The force eventually left Persia in November 1920.

Spying Efforts

British efforts against the conspiracy began in Europe. British spies were in Constantinople, Cairo, and Persia. Their main goal was to stop the expedition before it reached Afghanistan. They also wanted to pressure the Emir to stay neutral. British intelligence officers in Persia intercepted messages between the expedition and Prince Reuss in Tehran. These messages included details of meetings with the Emir and requests for weapons and men.

The most important spy success was a message from von Hentig asking for Turkish troops and mentioning the need for "internal problems" in Afghanistan. This message reached Russian intelligence and then the Viceroy, who sent an exaggerated summary to the Emir. He warned the Emir of a possible coup funded by the Germans and a threat to his life. In 1916, British intelligence in India captured letters from the Indian provisional government. These letters, written on silk cloth, were hidden in a messenger's clothing. This event was called the Silk Letter Conspiracy.

Diplomatic Actions

New Delhi warned the Afghan Emir about the approaching expedition even while trying to stop it in Persia. After it entered Afghanistan, the Emir was asked to arrest the members. However, Habibullah played along with the British without fully obeying. He told the Viceroy he would remain neutral. British intelligence later found out that the expedition carried very strong letters from the Kaiser and the Turkish Sultan.

By December 1915, New Delhi felt more pressure was needed. Viceroy Hardinge suggested that a letter from King George might help Habibullah stay neutral. King George V personally sent a handwritten letter to Habibullah, praising his neutrality and promising more money. The letter, which called Habibullah "Your Majesty," was meant to make him feel like an equal partner. It worked: Habibullah sent word that he could not formally acknowledge the letter due to political pressure, but he would remain neutral.

After the draft treaty in January 1916, worries grew in Delhi about trouble from tribes in the North-West Frontier Province. That spring, Indian intelligence heard rumors of letters from Habibullah to his tribal chiefs, urging a holy war. Alarmed, Hardinge called 3,000 tribal chiefs to a big meeting. He showed off aerial bombing displays and increased British payments to the chiefs. These actions helped convince the tribes that Britain's position was strong.

Impact of the Expedition

On Afghanistan

The expedition greatly affected Russian and British influence in Central and South Asia. It almost pushed Afghanistan into the war. The offers and connections made between the mission and Afghan politicians started a process of political change in the country.

Historians say that the expedition was too early in its political goals. However, it planted the ideas of independence and reform in Afghanistan. These ideas gained strength by 1919. Habibullah's neutrality angered many of his family members and advisors. His demand for full independence in foreign policy was rejected in early 1919. Habibullah was killed two weeks later. The Afghan crown first went to Nasrullah Khan, then to Habibullah's younger son, Amanullah Khan. Both had strongly supported the expedition. This change led to the Third Anglo-Afghan War. After some small fights, the Anglo-Afghan Treaty of 1919 was signed, and Britain finally recognized Afghanistan's independence. Germany was one of the first countries to recognize the new Afghan government.

For the next ten years, Amanullah Khan made many social and constitutional changes. These changes were first suggested by the Niedermayer-Hentig expedition. Women in the royal family removed their veils, and schools were opened to women. The education system was reformed with a focus on non-religious subjects, and teachers came from outside Afghanistan. A German school in Kabul even offered a "von Hentig Fellowship" for studying in Germany. Medical services were improved, and hospitals were built. Amanullah Khan also started industrialization and nation-building projects, with a lot of German help. By 1929, Germans were the largest group of Europeans in Afghanistan. German companies like Telefunken and Siemens were very important in Afghanistan. The German airline Deutsche Luft Hansa was the first European airline to fly to Afghanistan.

Soviet Eastern Policy

As part of their anti-British policies, the Soviet Union planned to cause political unrest in British India. In 1919, the Soviet government sent a diplomatic mission. This mission connected with the remaining Austrian and German members of the Niedermayer-Hentig expedition in Herat. It also talked with Indian revolutionaries in Kabul. The mission suggested a military alliance with Amanullah against British India. These talks failed before British Indian intelligence found out about them.

Other plans were explored, including the Kalmyk Project. This was a Soviet plan to launch a surprise attack on the north-west frontier of India through Tibet and other Himalayan states. The goal was to use these places to start a revolution in India. Historians believe this plan might have been influenced by Mahendra Pratap's advice to the Soviet leaders in 1919. He pushed for a joint Soviet-Afghan campaign into India. The plan was to arm the local people in North-East India with modern weapons, disguised as a scientific expedition to Tibet. This project had Lenin's approval.

Pratap, who was very interested in Tibet, tried to spread anti-British propaganda there as early as 1916. He continued his efforts after returning from Moscow in 1919. The planned expedition was eventually canceled. Pratap then tried to pursue his goal alone but was unsuccessful.

British India's Response

The Hindu–German Conspiracy, Pratap's mission in Afghanistan, and the active revolutionary movements in India led to the appointment of a committee in British India in 1918. This committee, chaired by Sydney Rowlatt, investigated German and Russian links to the Indian militant movement. Based on the committee's recommendations, the Rowlatt Act (1919) was put into effect in India.

Many events after the Rowlatt Act were influenced by the conspiracy. British Indian Army troops were returning from war to economic problems in India. News of Indian volunteers fighting for the Turkish Caliphate also reached India. Mahendra Pratap was watched by British agents during his travels. The Third Anglo-Afghan War began in 1919 after Emir Habibullah was killed and Amanullah took power. When Pratap heard about the war, he returned to Kabul using air transport from Germany.

At this time, the pan-Islamic Khilafat Movement began in India. Gandhi, who was not well-known yet, started to become a major leader. His call for protests against the Rowlatt Act led to widespread unrest. The situation, especially in Punjab, quickly got worse. The British feared a bigger rebellion was brewing. The Amritsar massacre, where many people were killed, was a result of the Punjab administration's plan to stop such a conspiracy.

What Happened Later

After 1919, members of the Provisional Government of India and Indian revolutionaries sought Lenin's help for the Indian independence movement. Some of these revolutionaries became involved in the early Indian communist movement. Mahendra Pratap traveled under Afghan nationality for years before returning to India after 1947. He was later elected to the Indian parliament. Barkatullah and C.R. Pillai returned to Germany. Barkatullah later moved back to the United States, where he died in 1927. Pillai was killed in 1934.

Ubaidullah Sindhi went to Soviet Russia, where he stayed for seven months. He studied socialism and was impressed by Communist ideas. He then went to Turkey, where he started a new phase of the Waliullah Movement in 1924. He issued a document for India's independence from Istanbul. Ubaidullah traveled through Islamic holy lands before being allowed to return to India in 1936. He died in 1944.

Both Niedermayer and von Hentig returned to Germany and had successful careers. Niedermayer was honored and asked to lead a third expedition to Afghanistan in 1917, but he declined. He served in the German army before retiring and joining the University of Berlin. He was called back to duty during World War II and died in a Soviet prisoner of war camp in 1948.

Werner von Hentig was honored by the Kaiser himself. He became a diplomat, serving as consul general in several countries. In 1969, Afghan King Mohammed Zahir Shah invited von Hentig as a guest of honor for the fiftieth anniversary of Afghan independence. Von Hentig later wrote his memoirs of the expedition.

Images for kids

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |