Operation Oyster facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Oyster |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second World War | |||||||

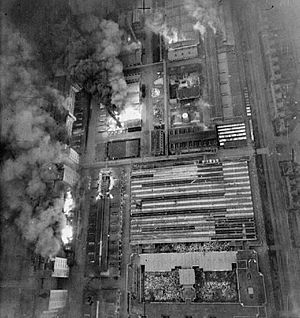

Bostons fly past the burning Philips Emmasingel plant during the Eindhoven raid |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

93 light bombers

|

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 62 aircrew 15 aircraft lost 57 damaged |

1 Fw 190 (against a diversion) 7 killed |

||||||

| Around 150 civilians killed Philips Works suffered significant damage . |

|||||||

Operation Oyster was a daring bombing raid by the Royal Air Force (RAF) during World War II. On December 6, 1942, RAF planes attacked the Philips factories in Eindhoven, Netherlands. Philips was a huge electronics company. They made important parts like vacuum tubes for radio communication. Before the war, Philips was also known for its research in infrared and radar technology. The raid had to happen during the day. This was to make sure the bombs hit their targets accurately. It also helped keep Dutch civilians safe.

Eindhoven was too far for fighter planes to escort the bombers. The large, four-engine night bombers of RAF Bomber Command were too slow and easy to hit during the day. So, No. 2 Group RAF, which had medium day bombers, was chosen for the mission. To help them survive, other raids were planned to trick German defenders. Almost all of 2 Group took part. It was their biggest and most successful operation of the war.

Contents

Why the Raid Happened

Philips: A Key Target

In April 1942, British officials made a list of important targets. These were in countries occupied by Germany. The Philips radio and vacuum tube factory in Eindhoven was the top target. It was seen as important as any target in Germany. Philips was a leader in electronics. It employed many people in Eindhoven. Its main production was at the huge Strijp works. There was also a smaller factory, the Emmasingel works, nearby.

Philips had made big steps in making vacuum tubes before the war. They had some of the best scientists in the world. The British believed Philips made a third of the radio tubes used in German military gear. They also worried Philips was helping Germany with radar technology.

The Philips factories were in the middle of a Dutch city. This meant a large night raid by Bomber Command was not possible. It would cause too many civilian deaths. For accurate bombing, the attack had to be in daylight. Sadly, about 150 civilians lost their lives in the raid.

Eindhoven was about 70 miles (110 km) inland from the coast. This was too far for fighter planes to escort the bombers. Using Lancaster bombers was considered but rejected. They were too easy to hit by German fighters in daylight. de Havilland Mosquito planes were also thought of. But the Philips factories were too big a target for the bombs Mosquitos could carry.

The RAF's 2 Group

No. 2 Group RAF was the only group of day bombers in RAF Bomber Command. It had ten medium bomber squadrons. They were based at airfields in Norfolk, England. This group worked with Fighter Command against the German air force, the Luftwaffe. They flew daylight raids against ships and targets in France. These raids were at medium heights through German fighter defenses.

However, the two large Philips plants in Eindhoven needed a bigger attack. The usual twelve-aircraft formations were not enough. Bomber Command decided to use all ten squadrons of 2 Group. This meant using four types of medium bombers: the Lockheed Ventura, Douglas Boston, North American B-25 Mitchell, and de Havilland Mosquito. These planes had different performances. It was the most ambitious raid ever for 2 Group. The raid was approved on November 9, 1942, and named Operation Oyster.

Getting Ready for the Raid

Practice Flights

The first big practice happened on November 17. Ventura crews quickly learned that flying so low was tricky. The air pushed back from other planes' propellers. This made their planes skid and hard to control. Flying low meant no time to recover from mistakes. Pilots had to be very careful to stay in formation. They focused on the plane in front of them. The lead pilot had to think about all the planes behind him.

Flying low over Holland, pilots and navigators had to watch for obstacles. These included trees, chimneys, and power lines. Another danger was birdstrikes. Birds on the coast were often large. When startled by plane noise, they would fly up. Bird strikes were a big risk for 2 Group.

The first plan was for Venturas to attack first. Then Bostons, Mitchells, and Mosquitos would follow. All planes would fly low until just before the target. Then they would climb to 1,500 feet (460 m) and dive slightly to bomb. The first practice was not good. Planes arrived at different times and from different directions. It was clear they needed more time to form up. Also, the Mitchell crews were not ready for such a tough raid. It was also realized that if Venturas dropped incendiary bombs first, the smoke would hide the target for later planes.

The order of attack was changed. Bostons would attack first, then Mitchells and Mosquitos, with Venturas last. Take-off times were moved earlier to give planes more time to get into formation. A second practice by Venturas was much better. Crews also practiced bombing at low levels (1,000 to 1,500 feet) in different formations. A third practice on November 20 was better. But the Mitchell squadrons (98 and 180) were removed from the raid. Their crews were still too new. This left 8 squadrons for the attack.

The Attack Plan

The plan for the attack was given on November 17, 1942. Training started right away. Wing Commander James Pelly-Fry of 88 Squadron was chosen to lead. He was an experienced pilot. He would fly one of the two low-level lead Bostons to the Emmasingel factory. He would be the first to reach the target.

Normal raids by 2 Group involved 6 to 30 bombers. They flew at medium heights and met fighter escorts. But the Eindhoven raid was different. It would be flown at a very low level from start to finish. Flying low would avoid radar detection. It would also limit exposure to anti-aircraft fire. And it would make it harder for German fighters to attack.

None of the crews had flown such a large mission so close to the ground. The four types of bombers had different ranges and speeds. To overwhelm defenses and limit losses, all planes aimed to be over the target, drop their bombs, and leave in ten minutes. This needed very careful planning. Venturas were the slowest, Bostons and Mitchells were medium speed, and Mosquitos were the fastest. The plan was based on the Venturas' limits, as Eindhoven was near their maximum range.

Planes would fly in pairs, in a step-like formation to the right. Up to six planes could be grouped. More than that made formation flying too hard. The big challenge was getting many planes to arrive at exact times. Large formation flying at tree-top level was new. The attacking force had 48 Venturas (from 21, 464 (Australian), and 487 (New Zealand) Squadrons). There were 36 Bostons (from 88, 107, and 226 Squadrons). And 10 Mosquitos (from 105 and 139 Squadrons).

All planes were to approach, attack, and leave the target at their fastest speed. Twelve Bostons, ten Mosquitos, and thirty-one Venturas would hit the main Strijp Group works. Twenty-four Bostons and seventeen Venturas would attack the Emmasingel radio tube factory. This was half a mile south-east of the main complex.

Boston and Mosquito bombers carried four 500-pound (227 kg) high explosive bombs. These bombs had a very short delay (0.025 seconds). This was to stop them from sliding away before exploding. After dropping bombs, planes would fly home at full speed, skimming the ground.

After the third practice, it was decided that one Boston from each squadron would fly low all the way. This was to draw German anti-aircraft gunners' attention away from the main force. The low-flying Bostons' bombs had an eleven-second delay. This was to prevent the planes from being caught in their own explosions. The Venturas following them carried forty 30-pound (14 kg) incendiary bombs. These were phosphorus, which would stick and burn. They also carried two 250-pound (113 kg) high explosive bombs. These had a 30 or 60-minute delay. This was to make it harder for firefighters and rescue workers.

Mosquitos would follow the Bostons' route. Venturas would fly slightly south before turning to Eindhoven. The three groups aimed to arrive over the target very close together. The attack was planned to finish within 10 minutes. Bostons would drop bombs at 12:30 p.m. Mosquitos would follow at 12:32 p.m. Venturas would drop their bombs and incendiaries at 12:36 p.m.

After bombing, Venturas would turn west. Bostons would fly north for 2 miles (3.2 km) and then turn west. Both groups aimed to reach the coast at the same time. Mosquitos would generally fly north first but could choose their own way back.

Spitfires from No. 12 Group RAF would escort the bombers home from the coast. They would go up to 5 miles (8 km) inland. To protect the bombers even more, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) planned diversionary raids. Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers were sent to the German airbase at Abbeville. A larger group of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses went to Lille, with Spitfire escorts. Eight North American P-51 Mustang fighters would also make ground attacks.

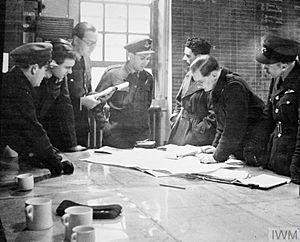

On December 2, crews were briefed on the raid. No one could leave the air bases. Mail was stopped, and phones were guarded. The next morning, December 3, the weather was bad. The raid was delayed. Finally, on Sunday, December 6, the weather over Eindhoven was good.

The Raid Begins

Distracting the Enemy

The day started with the Eighth Air Force launching its diversion raids. Nineteen B-24s were sent to attack the German airfield at Abbeville. An hour later, 66 B-17s took off to bomb the rail yard at Lille. During these operations, the US bombers also flew fake runs over the English Channel. This was to make it look like normal flights.

German air controllers detected the US bomber groups. Luftwaffe fighter planes were sent to stop them. The B-24s heading to Abbeville were called back. But six planes didn't get the message and continued. They were attacked over the target and lost one B-24. But they still bombed the airfield at 11:24 a.m. Thirty-five minutes later, the B-17s met their Spitfire escorts. They arrived over Lille and bombed the rail works at 12:10 p.m. Thirty-seven of the US bombers hit their target well. As they left, 20 to 30 enemy planes attacked them. They lost one B-17.

Flying In Low

From 11:15 to 11:30 a.m., the eight squadrons of 2 Group took off. They flew below 100 feet (30 m) in radio silence. They formed up by plane type and headed for the coast. The Southwold Lighthouse guided the Bostons and Mosquitos. The Venturas flew slightly south, over Orfordness Lighthouse. German radar did not detect them. The planes flew so low over the North Sea that their propellers made waves.

After 45 minutes, the Dutch coast appeared. Landfall was planned at Colijnsplaat. This town is at the mouth of the Oosterschelde estuary. The leading Bostons arrived. German anti-aircraft guns (flak) along the coast were surprised. They fired only a little as the Bostons passed.

The Bostons followed their path up the Oosterschelde estuary. They hugged the north coast for 30 miles (48 km) to Bergen op Zoom. In the estuary, the first big danger appeared: sea birds. The noise of the planes startled them, and they flew into the air. The risk was known, but there were more birds, and they were bigger than expected. As planes flew through them, some birds broke windscreens. Some went into cockpits and hurt aircrew. Others bent fuel pipes and damaged wings. In one plane, two gulls smashed through the nose, hitting the navigator's legs. The wind pulled his maps out. He had to navigate the rest of the way from memory.

Three minutes behind were the Venturas. German gunners were ready for them. Worse, the Venturas missed their landing spot. They arrived a mile south over the island of Walcheren. German flak defenses were strong there. Tracer fire lit up the sky. The sea seemed to churn white below them. A Ventura was hit and crashed into the sea. A moment later, another was hit on the right side of the cockpit. The pilot was hurt but landed the plane in a field.

Some German fighters were returning from a battle over Lille. They found the low-flying bombers. Rudolph Rauhaus in his Focke-Wulf Fw 190 damaged a Ventura. It crash-landed on the Reimerswaal peninsula. Three of the six crew survived and were captured.

As the planes neared the top of the estuary, they saw Woensdrecht Air Base. This was home to German fighters. As they flew past, German Focke-Wulfs took off. They turned towards the bombers. Mosquito pilot Charles Patterson said, "They looked so normal, just like Spitfires taking off in England, that it was hard to realize they were coming up to kill you."

The planes kept low, rising slightly to clear hedges and houses. Pilots and navigators worked together. They pointed out trees, chimneys, power lines, and other things to avoid.

Following the Bostons, the Mosquito pilots saw enemy planes approaching. Squadron Leader D. Parry and Flight Lieutenant W. Blessing turned towards them. They were soon under fire. They sped up, but the Focke-Wulf 190 was as fast as the Mosquito. Parry flew as fast as he could, watching his pursuers. He escaped and rejoined the attack. Blessing was chased for ten minutes. He got away but was too late for the mission. He returned to base with his bombs.

Pelly led the Bostons and Mosquitos towards Turnhout. Flying so fast and low was a navigation challenge. If he was wrong, coming around again would be a disaster. At Turnhout, he turned north-east. This would take his squadron 24 miles (39 km) to Eindhoven. On his maps, Pelly had seen a rail line going into Eindhoven from the south. He desperately looked for it. To his relief, he saw a puff of white smoke in the distance. It was a train! He stayed to the left of the raised railway. As they reached Eindhoven, two huge factory buildings appeared. The 24 Bostons from 88 and 226 Squadrons headed for Emmasingel. The 12 Bostons from 107 Squadron split off left. They followed Squadron Leader R.J. McLachlan to the big buildings at Strijp.

The Attack on Philips

Behind them was the Mosquito group. They were due to arrive at the target two minutes after the Bostons. They had to be careful not to fly too fast and overtake the Bostons. Behind the Mosquitos came the Venturas. They had taken a slightly longer route to Oostmalle to give more time before turning to Eindhoven. They would stay low and drop their incendiary bombs on the factory rooftops.

Pelly-Fry and his wingman led 88 and 226 Squadrons to the Emmasingel works. Their planes came under fire from German anti-aircraft guns and machine-guns on the factory roofs. They fired back with their own machine-guns. Behind them, their squadron mates climbed to 1,500 feet (460 m) for their shallow dive attack. Pelly reached the factory and dropped his bombs. But as he flew over, his plane was hit hard in the right engine and wing. The wing dropped, and he was flying almost vertically. He struggled to get control and slowly leveled his wings. Pelly said the plane felt very heavy. He had trouble turning it left. While the time-delay fuses counted down, he left the area at full power, heading north.

It had been a quiet Sunday afternoon in Eindhoven. No air raid sirens had sounded. The day before was St. Nicholas Day, and families were having lunch. The first sign of trouble was a steady humming sound of engines, growing louder. This was a clear sign of British planes. People started coming outside to see what was happening. Suddenly, loud German anti-aircraft guns fired. British bombers' machine guns answered. Those near the factory quickly ran back inside as bombs began exploding.

The Bostons of 88 and 226 Squadrons had climbed to 1,500 feet. Pilot Jack Peppiatt of 88 Squadron felt very exposed up there. They leveled off, then dropped into a shallow dive. They released their bombs, each plane dropping four 500-pound (227 kg) bombs between 12:30 and 12:33 p.m. The attack happened very quickly. The factory shook, and smoke filled the air.

A similar attack happened at the Strijp works. The Bostons of 107 Squadron bombed it. The Strijp tower clock stopped at 12:32 p.m. It stayed stuck at that time for the rest of the war. With bombs dropped, the Bostons flew low and followed Pelly-Fry, who was heading north. This was the plan for only a couple of miles. Then they were to turn west for the coast. But Pelly-Fry kept heading north. The Bostons followed him.

Behind the Bostons came the Mosquitos. They tried not to overtake them. They were due to arrive just after the Bostons. They also climbed to 1,500 feet. As they climbed, three Focke-Wulfs attacked them. The Mosquito was the only plane in the raid with no defensive weapons. One Mosquito turned to run. German fighters chased it. It flew at full speed and avoided damage. It also pulled the German fighters away from the slower Bostons. The remaining Mosquitos dropped their bombs on the Strijp works. Then they flew low and looked for a way out.

Following both groups were the Venturas. They carried their incendiary bombs for a low-level attack at 12:36 p.m. As they came in, smoke billowed into the air, making it easy to find the target. But flying through the smoke and hitting the target was hard. The smoke hid the buildings and made it tough to avoid obstacles. As Venturas dropped their incendiaries, the fires grew. It became harder to see. Many pilots struggled to get their planes over the buildings.

One Ventura attacking the Strijp complex was hit. It flew into a cloud of smoke. In the darkness, it flew straight into a building and exploded. Fire, smoke, and bombing planes filled the air. Another Ventura was seen getting hit and catching fire. It flew straight through a Dutch house, exploding as it came out. Another plane dropped its incendiaries, but some phosphorus splattered onto its tail, setting it on fire. It crashed and exploded. The Venturas were dropping their bombs but suffered high losses. Pilot Stephen Roche said, "The flak and machine-gun fire were terrific, and once we bombed it was every man to himself." German gunners on rooftops were seen firing their guns even as the buildings they stood on burned or exploded. Several other Venturas were lost. After dropping their bombs, the planes dived to ground level and flew home, skimming the ground.

Pelly-Fry's plane, hit during the bomb run, had its right aileron shot off. This made turning left very hard. As he struggled for control, his plane went north. The Bostons following him went right past their turn point. Soon, they wondered what was happening. They were supposed to fly north for a couple of miles, then turn sharply west for the coast. Instead, they kept going north, towards Rotterdam. The northern route to the coast was longer. Rotterdam was heavily defended. Their Spitfire escorts would be waiting over Colijnsplaat. Eventually, some Bostons turned west. The rest followed north to Rotterdam. Soon, they were dodging the tall cranes of the shipping yards. This was dangerous, but they all made it through.

The Mosquitos followed the Bostons for their bomb run on the Strijp works. Patterson remembered, "In the distance I could see masses of Bostons whizzing about across the trees at low level to port. I came straight down to ground level. Now the Mosquitoes all split up and we all had to come home separately." Mosquito crews were free to choose their own route home to the north on this mission.

The Flight Home

Mosquitos were much faster and had no defensive weapons. It made no sense to tie them to the Bostons and Venturas. After flying north, some turned west. Coming up behind the Bostons, the Mosquitos saw them weaving and sliding. The Bostons were flying low and as fast as possible. German fighters now made it even more dangerous. They were lucky not to have any crashes. Boston pilot Jack Peppiatt said, "After a few minutes settling down it all went up with a bang as Fw 190s appeared. Without doubt the next 20 minutes or so were full of action and not a little confusion. Some 10 or 20 aircraft were screaming along, full throttle in a loose mass. No one wanted to be at the back where the Focke-Wulfs were coming in to attack and wheeling away for another go."

Bostons were soon joined by some Mosquitos. The Mosquitos hoped to gain protection from the Bostons' guns. But they soon thought better of it and sped past them. Luckily, the attacks from behind were limited because of the low altitude. Fighters coming from above had to turn away early. There was no room to dive through the group.

Except for the bomb run, a pilot never flew straight and level over enemy territory. The rear gunner was the pilot's eyes in the back. For a crew to get home, the rear gunner had to see the enemy fighter. As it got close, the gunner would wait. He would call out to the pilot just as the fighter was about to fire. The gunner would fire his machine guns. But accuracy was hard with the plane jerking around. Hitting the enemy was less important than the crew's survival. In the running fight to the coast, pilots slid and weaved. They listened for the cry of "Jink!"

Flak started up again as they reached the coast. It followed them out over the sea. One Boston was hit and crashed. As they pulled away, larger guns joined in. They made huge splashes with their shells. They hoped to knock a plane down with the spray. This scared the crews. Many thought the splashes were their fellow planes falling. But they all managed to get clear.

The Mosquitos spread out on different return routes. Patterson decided it might be safer to avoid the planned route the Bostons were taking. Enemy fighters might have gathered over the west coast to stop them. He headed north for the Zuider Zee. He planned to go west past Den Helder. Fellow Mosquito pilot John O'Grady followed him. O'Grady was a young Canadian pilot who had trained under Patterson. The two planes flew north over the causeway, low and fast, 20 feet (6 m) over the water. As they neared the narrow point where Texel met Den Helder, the Germans there fired a fierce barrage of flak. Patterson flew through it without being hit. But O'Grady's plane was hit. They kept going. But a short way out over the North Sea, Patterson's navigator called out, "He's gone into the sea!" Patterson circled back. But all he found was churning water where his friend's plane had disappeared.

German fighters had indeed gathered off the coast along the Bostons' route. Wing Commander Peter Dutton, the leader of 107 Squadron, was shot down 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) from Katwijk aan Zee. Two more planes from 107 Squadron were lost to fighter attacks over the water. Another from 226 Squadron was lost off Scheveningen.

After the Raid

What Happened Next

Back in England, waiting newspaper reporters met the returning planes at their airfields. They crowded around the crews and took pictures of the damaged planes. That night, parties were held. A concert with famous radio entertainers was given. The next day, the raid was celebrated in the newspapers. The crews all got three days off.

Eindhoven was freed on September 18, 1944. An inspection of the Philips factories found that Philips' leaders had quietly resisted the Germans. They also found that the German system of control had actually caused the most damage to Philips' production.

Losses and Damage

Sixty-two aircrew members were lost. Fifteen aircraft were lost: nine Venturas, four Bostons, and one Mosquito. One plane crashed into the sea, and another crashed in England. This was a 16% loss rate. Thirty-seven Venturas, thirteen Bostons, and three Mosquitos were damaged. Seven were seriously damaged. This was 57% of the force. The Venturas had a 20% loss rate and three crash-landings in England. This was a loss rate that could not continue.

German fighters caused few losses and little damage. The bombers were hard targets at low levels. One Mosquito was attacked by a Fw 190 near Eindhoven. It stopped its bombing run after escaping the fighter. At least 31 planes had bird strikes. Some hit trees. Several Venturas likely hit houses while bombing through smoke. Light flak damaged some planes and possibly shot down others. The group had to stop operations for ten days. This was to repair planes and replace losses. One B-17 and one B-24 were lost in the two diversion raids. One escorting Spitfire was also lost. One Fw 190 was shot down.

Sadly, about 150 civilians lost their lives. Seven German soldiers also died.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |