Patio process facts for kids

The patio process was a special way to get silver out of ore (rocks that contain metal). Silver isn't usually found pure in nature. Instead, it's mixed with other materials. So, people needed a way to separate the pure silver. This process used a liquid metal called mercury to collect the silver.

A man named Bartolomé de Medina is said to have invented the patio process in Pachuca, Mexico, in 1554. It became the main way to get silver from ore in Spanish colonies in the Americas, replacing an older method called smelting. While some people knew about using mercury to get metals before, the patio process was the first time it was used on a very large scale. Other similar methods were developed later, like the pan amalgamation process.

Contents

How the Patio Process Started

Bartolomé de Medina was a successful Spanish merchant. He became very interested in the problem of less and less silver being found in the Americas. By the mid-1500s, silver production was dropping because the best ores were running out. Also, it was becoming more expensive to mine. New laws had stopped the enslavement of Native Americans, which meant miners had to pay workers or use expensive African slaves. This made it too costly to mine anything but the highest quality silver.

Medina first tried to learn about new smelting methods in Spain. Then, a German man known as "Maestro Lorenzo" told him that silver could be taken from crushed ores using mercury and salty water. With this idea, Medina went to New Spain (Mexico) in 1554. He set up a special refinery (a place where metals are purified) to show how well this new method worked.

Medina is usually given credit for adding "magistral" to the mix. Magistral was a type of copper sulfate that came from other minerals. It helped the mercury and silver mix together better. Some historians think that the local ores already had enough copper sulfate. But others argue that adding magistral made the process work much more reliably on a large scale. No matter if his idea was completely new or not, Medina promoted his process to local miners. He even got a special permission from the leader of New Spain. Because of this, he is known for inventing the patio process for getting silver.

This method was so good that when German experts came to America later, they were very impressed. They said they couldn't find a better way to get silver in that region. One German refiner, Friedrich Sonneschmidt, said that no other method could be cheaper or better than the patio process. It was so effective that miners could still make money even if the ores had very little silver in them.

How the Patio Process Worked

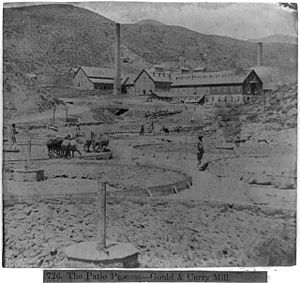

Before the process began, large pieces of silver ore had to be broken down. At the refinery, the ore was ground into a fine sand, called harina. This was done using an arrastra or a stamp mill. These machines had heavy iron stamps that crushed the ore against a hard surface.

Next, the harina was placed in large piles, often weighing 2,000 pounds or more. To these piles, workers added salt, water, magistral (which was an impure form of copper sulfate), and mercury. This mixture was then stirred. Sometimes, bare-legged Native American laborers mixed it. Other times, horses or mules walked over the piles to mix them. The mixture was spread out in a thin layer, about 1 to 2 feet thick, in a patio. A patio was a shallow, open area with low walls.

After six to eight weeks of mixing and soaking in the sun, a complex chemical reaction happened. The silver in the ore changed into pure metal and then mixed with the mercury. This created a silver-mercury mixture called an amalgam.

Then, the amalgam was washed and strained through a canvas bag. After that, it was put into a special oven with a hood. Heating the amalgam made the mercury turn into a vapor (a gas), leaving the pure silver behind. The mercury vapor would then cool down and turn back into liquid mercury on the hood. This collected mercury could be used again.

The amount of salt and copper sulfate added depended on the ore. It could range from a quarter of a pound to ten pounds per ton of ore. Deciding how much of each ingredient to add, how much mixing was needed, and when to stop the process was the job of a skilled person called an azoguero (which means "quicksilver man"). The process usually lost about one to two times the weight of the silver recovered in mercury.

The patio process was the first type of mercury amalgamation. However, it's not fully clear if this open-air method or a similar one, where amalgamation happened in heated containers, was more common in New Spain. The earliest known drawing of the patio process is from 1761. There is good evidence that both methods were used early on in New Spain. In Peru, open patios were never used. Instead, refiners in the Andes placed the crushed ore in stone tanks that were heated by fires underneath. This helped speed up the process because of the very cold temperatures in the high mountains. Both methods needed the ore to be crushed, so mills were quickly built once amalgamation started. In the Andes, water mills were common. But in New Spain, where water was scarce, mills were often powered by horses or other animals.

Because amalgamation needed a lot of mercury, increasing mercury production was very important for increasing silver production. A key source of mercury was found at Huancavelica, Peru, in 1563. More mercury came from Almadén, Spain, and Idrija in present-day Slovenia. From shortly after the patio process was invented until the end of the colonial period, the Spanish government controlled all mercury production and distribution. This ensured a steady income for the crown. Changes in mercury prices usually led to similar changes in silver production. The government could even use mercury prices to control how much silver was produced in its colonies.

Big Impact on History

The patio process changed silver refining in the Americas. It solved the problem of falling silver production in the mid-1500s. It also led to a huge increase in silver production in New Spain and Peru. Miners could now make a profit even from lower-quality ores. Places that had a lot of ore but were too far from people or forests for the old smelting method to work, like Potosí in modern-day Bolivia, now became profitable. Because of this expansion, the Americas became the world's main producer of silver. Spanish America produced about three-fifths of the world's silver before 1900.

More silver production meant more demand for workers. In New Spain, workers were first supplied by a system called encomienda or by enslaved Native Americans. Later, a rotating labor system called repartimiento was used. But by the early 1600s, most workers were free Native Americans who worked for wages or to pay off debts. These workers, called naboríos, were free and chose to work for food and pay. Spaniards often didn't trust naboríos, accusing them of stealing ore or running away after getting paid in advance. Still, mines in New Spain relied more and more on naboríos, who made up over two-thirds of the mine workers. Repartimiento workers made up about seventeen percent, and Black slaves made up another fourteen percent. White men usually worked as supervisors or mine owners.

The introduction of silver amalgamation also had a big impact on the native population of Peru. From 1571, when the process came to the Andes, to 1575, Peru's silver production grew five times larger. In 1572, to get enough workers for the expanding silver mines, Viceroy Francisco Toledo created a forced labor system called the mita. This system was based on an older Native American tradition of shared work. But under the Spanish, thousands of Native Americans were forced to work in silver and mercury mines for very low wages. Thirteen thousand forced laborers worked each year at the largest mine in the Americas, located at Potosí. Many Native American villages were abandoned as people tried to avoid the mita. Thousands either moved permanently to Potosí or fled their traditional homes to escape the forced labor. The Spanish government's control over refining through amalgamation also meant that Native Americans were cut out of what had once been a business they controlled. Refining was the most profitable part of silver production. Along with the mita, this exclusion helped turn Peruvian Native Americans into a poorly paid workforce.

The rapid increase in silver production and the making of silver coins, made possible by amalgamation, is often seen as a main reason for the price revolution. This was a time of high inflation (when prices go up a lot) in Europe from the 1500s to the early 1600s. People who support this idea say that Spain used silver coins from the Americas to pay its debts. This led to more money in Europe and higher prices. However, others argue that inflation was more caused by European government policies and population growth.

Even if its role in the price revolution is debated, the increase in silver production is often seen as a key part of how early modern world trade began. In the 1530s, China decided that all taxes inside the country had to be paid in silver. This created a huge demand for Spanish American silver. It also helped create large trade networks connecting Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas, as Europeans wanted to get Chinese goods.

See also

In Spanish: Método de patios para niños

In Spanish: Método de patios para niños

- Amalgam (chemistry)

- Dental amalgam

- Pan amalgamation

- Royal fifth

- Silver mining

- Spanish Empire

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |