Peter Williamson (memoirist) facts for kids

Peter Williamson (born 1730, died 1799) was a Scottish writer, entertainer, and inventor. People also called him "Indian Peter." He was born in a small farm in Scotland. When he was young, he was taken to North America against his will. Later, he managed to return to Scotland. He became a famous person in Edinburgh in the 1700s. He got the nickname "Indian Peter" because he spent time with Native Americans. He also used this experience to write a book and perform shows dressed as a "Red Indian."

Contents

Early Life in Scotland

Peter Williamson was born in a small farm called a croft in Hirnlay, near Aboyne, Scotland. His parents were "respectable though not rich." When he was very young, he went to live with his aunt in Aberdeen.

In those days, some people kidnapped children and took them away. These kidnappers were sometimes called "spirits." Many of these children were taken to North America. In January 1743, Peter Williamson was kidnapped while playing near the docks in Aberdeen. He wrote in his book that he was eight years old at the time. Some people thought that local officials in Aberdeen might have helped the kidnappers. Between 1740 and 1746, about 600 children disappeared from Aberdeen port.

Life in America: A New Start

Peter was taken to Philadelphia, a city in America. There, he was sold for £16 to a Scottish man named Hugh Wilson. Peter had to work for Wilson for seven years as an indentured servant. This meant he worked to pay off the cost of his journey. Hugh Wilson had also been kidnapped as a boy and sold into service. Because of this, he might have understood Peter's situation.

Peter said that Wilson treated him kindly. When Wilson died in 1750, just before Peter's seven years of service ended, he left Peter £120. He also gave Peter his best horse, saddle, and all his clothes. This helped Peter's life change for the better.

Becoming a Farmer

When Peter was 24, he married the daughter of a rich farm owner. He received 200 acres of land as a gift, which was near the edge of Pennsylvania. He decided to live there as a farmer.

On October 2, 1754, his farm was attacked by Cherokee Indians. Peter was taken prisoner. His house was robbed and then burned down. Peter wrote that he was forced to walk many miles, carrying things for the Cherokees. He also said he saw many terrible things, including murders and scalpings, while with them.

After several months, he managed to escape. He made his way back to his father-in-law's home. There, he learned that his wife had died while he was gone.

Joining the Army

Peter was asked to speak to the government in Philadelphia. He shared all the information he had learned during his time as a prisoner. While in Philadelphia, he joined an army group. This group was fighting in the French and Indian War. Over the next two years, he became a lieutenant, which is a high rank in the army.

Captured Again and Return to Europe

Peter was captured a third time, this time by French soldiers. He was marched to Quebec, a city in Canada. He was then allowed to be an "exchange prisoner." This meant he was sent on a ship to Plymouth in England, arriving in November 1756. Peter had a wounded left hand, so he was released from the army. He was given a small payment of six shillings to help him.

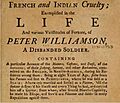

He decided to walk from Plymouth back to Aberdeen, which is about 1000 kilometers (620 miles). When he arrived in York with no money, his stories interested some important men. They encouraged him to write about his adventures. With their help, he published his book called French and Indian Cruelty, exemplified in the Life and various Vicissitudes of Fortune of Peter Williamson, who was carried off from Aberdeen in his Infancy and sold as a slave in Pennsylvania.

A thousand copies of his book were sold, and Peter earned £30. This money helped him travel more easily back to Scotland.

Back in Scotland: "Indian Peter"

As he traveled north, Peter started dressing like a "Red Indian." He gave shows where he demonstrated Native American life, including war-cries and dancing. This helped him sell more copies of his book, which he carried with him. In June 1758, he finally returned to Aberdeen, about 15 years after he was kidnapped.

While selling his books in Aberdeen, the local officials accused Peter of making false statements. They said he was lying about their involvement in his kidnapping. Since the same officials he was accusing were also judging him, he was found guilty. The extra copies of his book were taken and publicly burned at the mercat cross by the public executioner. Peter was forced to sign a paper saying his claims were false. He was fined five shillings and told to leave Aberdeen as a homeless person.

Life in Edinburgh

Peter then moved to Edinburgh, where he lived for the rest of his life. He opened a coffee house near Parliament House. This place became very popular with Edinburgh lawyers and their clients.

The poet Robert Fergusson wrote about Peter's coffee house in his poem The Rising of the Session:

This vacance [vacation] is a heavy doom

On Indian Peter's coffee-room

For a' his china pigs are toom [bottles are empty]

Nor do we see

In wine the soukar biskets soom [sugar biscuits swim]

As light's a flee

Some lawyers who had read Peter's book encouraged him to sue the Aberdeen officials. The case was heard in the Court of Session in Edinburgh. The judges all agreed that Peter was right. The main official of Aberdeen, four bailies (local magistrates), and the Dean of Guild had to pay Peter £100 as compensation.

Encouraged by this win, Peter decided to sue Bailie William Fordyce and others. He believed they were directly responsible for his kidnapping. The case went before James Forbes, a local judge in Aberdeenshire. It seemed that the people Peter was suing treated Forbes very well before he made his decision. Forbes then decided that they were innocent. This decision was announced publicly the next day.

However, the case was sent to the Court of Session in Edinburgh. Peter showed strong proof that the people he was suing were involved. In December 1763, the Court changed the earlier decision. Peter was given £200 in damages and 100 guineas for his legal costs.

Peter's Businesses and Inventions

Peter's new money allowed him to open a tavern in Parliament Close. The sign for his tavern said, Peter Williamson, Vintner From The Other World. This was a funny way to refer to his time in North America. A wooden statue of him dressed in Delaware Native American clothes stood near the entrance to advertise his place.

In 1769, Peter opened a printing shop. He taught himself how to print using a portable printing press he bought in London. He then invented his own portable printing press. He traveled to shows and fairs to promote his new invention. He also invented waterproof ink that could be used for stamping linen. This ink would not wash off even when boiled or bleached.

In 1773, Peter created the first street directory for Edinburgh. This was part of his idea to set up a regular postal service in the city. The directory listed streets and alleys, with addresses of lawyers, merchants, and other important people. It also included shops and taverns. This book helped people find their way around the city. It is also a very important historical record today. The directory cost one shilling and was updated regularly until 1796.

In 1776, he started a weekly magazine called The Scots Spy or Critical Observer. It was published every Friday and had articles and local news. This magazine only lasted from March to August 1776. He tried to start it again in 1777 as The New Scots Spy, but this second try also lasted only a few months.

In 1777, he married Jean, the daughter of a bookseller in Edinburgh. They later divorced in 1788.

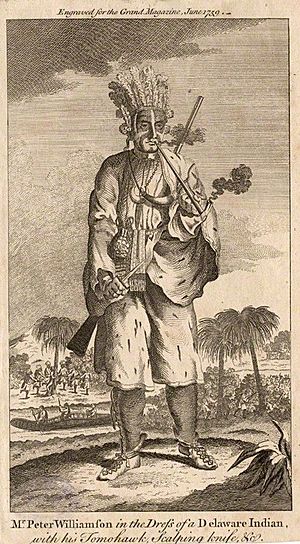

The National Portrait Gallery in London has a picture from 1759. It shows Peter Williamson in full "Delaware Indian" clothing, holding a tomahawk and a scalping knife. The artist John Kay also drew him in Native American costume around 1768. This drawing appeared in later versions of Peter's book. It is also in Kay's "Original Portraits," a collection of drawings of famous Edinburgh people.

Edinburgh's First Penny Post Service

Before 1774, Peter Williamson started a postal service in Edinburgh. He wrote about it in his 1774 Edinburgh Directory. He told people that he would deliver letters and packages up to 3 pounds in weight. This service covered anywhere within one mile of the city's mercat cross, and also places in North and South Leith. The service ran from his shop every hour and cost one penny. At first, Peter's postal service competed with the official postal service. But in 1776, Peter took over the official role as Postmaster for the penny post system.

Seventeen local shopkeepers across the city were paid to receive letters. This created the first "post offices." Four uniformed postmen were hired to deliver mail from Peter's shop to these other shops. Their hats had the words "Penny Post" on them, and they were numbered 1, 4, 8, and 16. This made the business seem bigger than it was.

This service was the first regular postal service in Scotland. Peter ran it for 30 years. In 1793, it became part of the General Post Office. Peter received £25 for his business and a pension of 25 shillings per year.

The penny post was officially made a law in 1799, after Peter's death.

The poet Robert Fergusson mentioned Peter again in his poem Codicile to Robert Fergusson's Last Will:

To Williamson, and his resetters

Dispersing of the burial letters

That they may pass with little cost

Fleet on the wings of penny-post

Death and Legacy

Peter Williamson died in January 1799, at the age of 74. He was buried on January 22.

He was buried in a part of the Old Calton Burial Ground in Edinburgh. His grave is not marked, but tour guides still talk about him today. His obituary, a notice about his death, appeared in "The Scots Magazine." It praised Peter and his many adventures, both good and bad.

His Street Directory business was taken over in 1800 by Thomas Aitchison.

Truth of His Story

The truthfulness of Peter Williamson's story about being captured by Native Americans was questioned almost as soon as his book was printed. Many historians have always doubted his story. In 1964, a historian named J. Bennett Nolan called Williamson "one of the greatest liars who ever lived."

While this might be a bit harsh, newer studies suggest that large parts of Peter's story might not be true. This includes possibly his marriage, his age when he was first kidnapped, and most importantly, his capture by Native Americans.

Even if Peter's story is "not to be trusted as an account of Indian Captivity," it is still an interesting example of a popular type of book from that time. These books were often called "narratives of unfortunates." It also shows how people wrote about Native Americans during the Seven Years' War. Like the book Robinson Crusoe, Peter's story helps us understand how people in colonial times thought about and described native peoples.

Peter Williamson's Writings

- French and Indian Cruelty, exemplified in the Life and various Vicissitudes of Fortune of Peter Williamson, who was carried off from Aberdeen in his Infancy and sold as a slave in Pennsylvania (York, 1757)

- Some Considerations of the Current State of Affairs Wherein the Defenceless State of Great Britain is Pointed Out (York, 1758)

- A Brief Account of the War in North America (Edinburgh, 1760)

- Travels of Peter Williamson amongst the Different Nations and Tribes of Savage Indians in America (Edinburgh, 1768) (reprinted 1786)

- A Nominal Encomium on the City of Edinburgh (Edinburgh, 1769)

- A General View of the Whole World (Edinburgh, c.1770)

- A Curious Collection of Moral Maxims and Wise Sayings (Edinburgh, c.1772)

- The Royal Abdication of Peter Williamson, King of the Mohawks (Edinburgh c.1775)

- Proposals for Establishing a Penny Post (Edinburgh c.1773)

Images for kids

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |