Phelps and Gorham Purchase facts for kids

The Phelps and Gorham Purchase was a huge land deal in 1788. Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham bought about 6 million acres of land in what is now western New York State. They bought the right to buy this land from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for $1,000,000. Then, they bought the actual land rights from the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy for $5,000.

This land was west of Seneca Lake, between Lake Ontario and the Pennsylvania border. It was a massive area, bigger than several U.S. states today! Phelps and Gorham were only able to get clear ownership for about 2 million acres, mostly east of the Genesee River. They also got a special 12-mile by 24-mile area called the Mill Yard Tract along the river.

Within a year, money problems and slow sales meant they couldn't make their payments for the land west of the Genesee River. They had to give up their claim to that part. They also sold much of the land they already owned at a lower price to Robert Morris, a rich financier and important American Founding Father. So, the Phelps and Gorham Purchase often refers only to the 2.25 million acres they actually managed to buy from the Iroquois.

Contents

How the Land Became Available

For a long time, the Iroquois Confederacy, made up of six Native American nations, lived in much of what is now New York State. They were a powerful group and kept most European settlers from moving into their lands, especially in the Finger Lakes region. The Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca were the original Five Nations. Later, the Tuscarora tribe joined them, becoming the Sixth Nation.

During the American Revolutionary War, four of the six Iroquois nations sided with the British. They hoped to stop American colonists from taking their land. These Iroquois warriors, led by Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, attacked American settlements. They burned homes, stole livestock, and took people captive.

The American colonists were very angry about these attacks. In response, General George Washington ordered Generals James Clinton and John Sullivan to lead a large army into Iroquois territory in 1779. Their mission was to destroy all Iroquois villages and crops.

Sullivan's army marched through the Finger Lakes region, destroying over 40 villages and vast amounts of stored corn and vegetables. This action didn't kill many Native Americans, but it destroyed their homes and food supplies. Thousands of Iroquois became refugees, suffering from starvation and disease. This greatly weakened their ability to fight in the war.

As Sullivan's army returned, they told exciting stories about the fertile lands they had seen. This made many people want to move to western New York.

The Treaty of Hartford

After the American Revolution, there was a lot of confusion about who owned the land in western New York. Both New York and Massachusetts claimed it based on old royal charters. To solve this problem, the two states signed the Treaty of Hartford in December 1786.

In this treaty, Massachusetts gave up its claim to the United States government. It also gave New York State the right to govern the region. However, Massachusetts kept a special "pre-emptive right." This meant Massachusetts had the first chance to buy land from the Iroquois nations before anyone else, including New York State.

After the U.S. Constitution was approved in 1787, the federal government agreed to this deal. In April 1788, Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham bought this "pre-emptive right" from Massachusetts. This didn't mean they owned the land yet. It only meant they had the exclusive right to negotiate with the Iroquois and get clear ownership of the land. They paid Massachusetts $1,000,000 for this right.

Meeting at Buffalo Creek

Phelps and Gorham faced competition from other groups who also wanted to buy the land. John Livingston tried to lease all the Iroquois lands for 999 years, but New York State said his deal was illegal. Other groups also tried to make deals with the Iroquois.

Phelps was smart and convinced many of his competitors to join his group. On July 8, 1788, Phelps met with the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy at Buffalo Creek. His goal was to make a treaty and buy a large part of their land.

Help from a Missionary

Phelps got help from Samuel Kirkland, a Presbyterian minister who worked with the Oneida tribe. Kirkland was appointed by Massachusetts to help with the land deal. Kirkland encouraged the Iroquois to sell their land. He believed they would become farmers only if they lost their hunting lands. Kirkland also gained from the sales, receiving 6,000 acres of land for himself.

Land Ownership Ideas

The Iroquois believed they owned the land. But Phelps convinced the chiefs that because they had sided with the British (who lost the war), and because the British had given up the lands in the 1783 peace treaty, the Iroquois could only keep the lands given to them by the United States.

Phelps and Gorham wanted to buy 2.6 million acres. However, the Iroquois refused to sell the rights to 185,000 acres west of the Genesee River.

The Mill Yard Tract

Phelps suggested that the Iroquois could use a grist mill to grind their corn, which would make their lives easier. The Iroquois asked how much land was needed for a mill. Phelps suggested a very large area west of the Genesee River. This area was 12 miles wide and 24 miles long, totaling about 288 square miles. It stretched from near present-day Avon north to Lake Ontario, including the area where Rochester is today. The Iroquois agreed to this.

Within this area, Phelps and Gorham gave 100 acres to Ebenezer Allen. He was supposed to build a grist mill and sawmill. This mill never did very well because there were few customers and no roads to it. Allen's land became the start of modern Rochester, New York. This area on the west bank of the Genesee River became known as the Mill Yard Tract.

The Purchase Agreement

Phelps and his company paid the Iroquois $5,000 in cash and promised to pay them $500 every year forever. This agreement gave them ownership of 2.25 million acres. This land was the eastern third of the territory Massachusetts had claimed. It stretched from the Genesee River in the west to the Preemption Line in the east. The Preemption Line was the boundary between the lands given to Massachusetts and those given to New York State.

Later, in 1794, the boundaries set by Phelps' agreement were confirmed again between the United States and the Six Nations in the Treaty of Canandaigua.

Area Boundaries

After the Revolutionary War, the U.S. government had promised the Iroquois chiefs in the 1784 Fort Stanwix treaty that their lands would remain theirs unless they agreed to sell them. The eastern boundary of the purchase was called the Preemption Line. It started at the New York-Pennsylvania border and went north to Lake Ontario. Massachusetts had the right to buy and resell land west of this line, while New York State had the right to govern it.

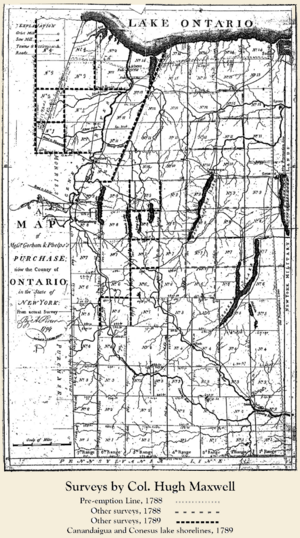

Phelps thought the Preemption Line went through Seneca Lake and included the former Iroquois town of Kandesaga (present-day Geneva). He wanted to make Geneva his headquarters. He hired a surveyor named Hugh Maxwell to map the land. Maxwell's survey, however, placed the line west of Seneca Lake and Kandesaga. Phelps was very upset because Geneva was not included in his purchase.

Maxwell's survey also mapped the western boundary of the purchase. He divided the land into 6-mile-wide sections. This work became known as "The First Survey."

Settlers Arrive

Phelps opened land sales offices in Suffield, Connecticut, and Canandaigua, New York. Over the next two years, they sold 500,000 acres to many buyers. People came from New England, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and even from England and Scotland. Many settlers were also soldiers who had fought under General Sullivan. There was a strong desire for land among people in New England, where it was becoming crowded.

Money Troubles

Many people bought land just to sell it quickly for a profit. For example, Oliver Phelps sold land to Prince Bryant, who then sold it a month later to Elijah Babcock, who then sold smaller parts to others. The company managed to sell about half of its land.

The Company Defaults

However, money values changed quickly. The value of the money Phelps and Gorham used to buy the land went up, making their debt much larger. This made it very hard to buy the remaining 1 million acres from the Iroquois. The company sold about 50 townships, but many buyers were just stockholders who took land instead of interest payments. Fewer new settlers bought land than expected, which reduced the company's income.

Phelps and Gorham couldn't make their second payment for the land west of the Genesee River. So, in March 1791, about 3.75 million acres of land went back to Massachusetts. Massachusetts then sold these rights to Robert Morris for $333,333. Morris was a very rich man who had helped fund the American Revolution. He paid about 11 or 12 cents an acre. Morris also bought the remaining lands that Phelps and Gorham still owned east of the Genesee River.

Survey Mistakes

When Robert Morris bought the land, everyone knew there were problems with the first survey done by Maxwell. The purchase papers even said there was a "manifest error" and a new survey was needed. Some people thought the errors were due to old surveying tools, but others suspected fraud. It was thought that an assistant surveyor might have changed the line to help his boss, Peter Ryckman, who wanted to control the area of Geneva.

Adam Hoops was hired to lead a new survey team. They found that Maxwell had made mistakes on both the eastern and western boundaries. Maxwell had not accounted for the difference between magnetic north and true north. Another survey team found that the Preemption Line actually ran through Seneca Lake and then north to Lake Ontario near Sodus Bay, about four miles west of Maxwell's line. This new line now divides the city of Geneva.

Hoops' new survey also showed that the western boundary of the Mill Yard Tract included a triangle-shaped piece of land, about 85,896 acres, that should have stayed with the Iroquois. To fix this, Morris's company gave the Iroquois an equal amount of land to the west, called the Triangle Tract. Morris then bought the rights to this Triangle Tract from the Iroquois. This land became part of the Morris Reserve. Hoops' corrected survey was accepted in 1795 and became known as the "Second Survey."

London Investors Buy Land

After buying the land from Massachusetts, Robert Morris quickly resold 12 million acres to a group of British investors called the Pulteney Associates. He sold it for more than double what he paid! Sir William Pulteney was the main investor. At the time, people who weren't U.S. citizens couldn't own land directly. So, the buyers sent Charles Williamson from Scotland. He became a U.S. citizen in 1792 so he could hold the land for them. Morris sold the land to Williamson for $333,333. Morris made a profit of over $160,000 on this deal.

The Pulteney Purchase, also known as the Genesee Tract, included all of today's Ontario, Steuben, and Yates counties, plus parts of Allegany, Livingston, Monroe, Schuyler, and Wayne counties.

Holland Land Purchase

Morris sold even more land in 1792 and 1793 to the Holland Land Company. This was a group of Dutch bankers. They also couldn't own land directly, so they hired American trustees. Morris convinced the New York Legislature to change the law, as the state wanted the lands to be settled.

The Holland Land Company wanted to get clear ownership from the Iroquois so they could sell the land. They held a meeting called the Council at Big Tree in 1797. Iroquois chiefs, Robert Morris, and representatives from the U.S. government and the Holland Land Company were there. The Seneca chief Red Jacket was a tough negotiator. The Dutch gave gifts to influential Iroquois women and offered payments to other chiefs to get their cooperation. They also set aside about 200,000 acres as reservations for the Iroquois tribes. This agreement was called the Treaty of Big Tree.

In 1802, the Holland Land Company opened its sales office in Batavia, New York. It was managed by Joseph Ellicott. This office stayed open until 1846. The building that housed the Holland Land Office is now a museum and a National Historic Landmark.

Morris Reserve

Robert Morris kept about 500,000 acres for himself. This was a 12-mile-wide strip along the eastern side of the lands he bought from Massachusetts, stretching from the Pennsylvania border to Lake Ontario. This area became known as the Morris Reserve.

At the northern end of the Morris Reserve, Morris sold an 87,000-acre triangle-shaped piece of land called the Triangle Tract. He also sold 100,000 acres west of the Triangle Tract to the State of Connecticut.

In 1796, John Barker Church took a mortgage on another 100,000 acres of the Morris Reserve. When Morris couldn't pay, Church's son, Philip Schuyler Church, got the land in 1800. Philip started the settlement of Allegany and Genesee counties by founding the village of Angelica, New York.

As mentioned, in September 1797, through the Treaty of Big Tree, Morris gained the remaining ownership of all the lands west of the Genesee River that the Iroquois still held. Morris paid $100,000 and promised yearly payments. He also created ten reservations for the Iroquois nations within the purchase, totaling 200,000 acres. The rest of the Morris Reserve was quickly divided and settled.

How Western New York Counties Were Formed

In 1802, the entire Holland Purchase and the 500,000-acre Morris Reserve to its east were separated from Ontario County. They were organized into a new county called Genesee County.

Over the next 40 years, Genesee County was divided many times to create all or parts of these counties: Allegany (1806), Niagara (1808), Cattaraugus (1808), Chautauqua (1808), Erie (1821), Monroe (1821), Livingston (1821), Orleans (1824), and Wyoming (1841).

Lasting Impact

Many of the people involved in these land sales were honored by having new villages named after them. Many of these original villages are still important towns today:

- Busti, a town in Chautauqua County, named for agent Paolo Busti.

- Cazenovia, a town and village in Madison County, named for agent Theophilus Cazenove.

- Ellicott, a town in Chautauqua County, named for surveyor Joseph Ellicott.

- Ellicottville, a town and village in Cattaraugus County, also named for Joseph Ellicott.

- Franklinville, a town and village in Cattaraugus County, named for agent William Temple Franklin, Benjamin Franklin's grandson.

- Gorham, a town in Ontario County, named for Nathaniel Gorham.

- Holland, a town in Erie County, named for the Holland Purchase or the Holland Land Company.

- Leroy, a town in Genesee County, named for Herman Le Roy, one of the buyers of the Triangle Tract.

- Mount Morris, a town and village in Livingston County, named for Robert Morris.

- Phelps, a town and village in Ontario County, named for Oliver Phelps.

- Williamson, a town in Wayne County, named for Charles Williamson.

In contrast, Angelica, a town and village in Allegany County, was named by landowner Philip Church for his mother, Angelica Schuyler Church.