Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society facts for kids

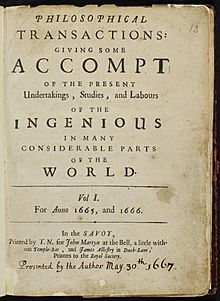

First volume title page

|

|

|

Abbreviated title (ISO 4)

|

Philos. Trans. R. Soc. |

|---|---|

| Discipline | Multidisciplinary science |

| Publication details | |

| Publisher | |

|

Publication history

|

6 March 1665 |

| Indexing | |

| ISSN | 0261-0523 (print) 2053-9223 (web) |

| OCLC no. | 1697286 |

| JSTOR | philtran1665167 |

| Links | |

|

|

The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society is a very old and important scientific journal. It is published by the Royal Society, a famous group of scientists. This journal started way back in 1665. This makes it the first journal in the world made only for science. It is also the longest-running science journal ever! The word "philosophical" in its name means "natural philosophy." This was the old way of saying "science."

Contents

What is Philosophical Transactions Today?

In 1887, this journal grew so much that it split into two parts. One part is called Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. It focuses on subjects like math, physics, and engineering. The other part is Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. This one is all about life sciences, like biology.

Both journals now publish special issues on certain topics. They also share papers from scientific meetings held by the Royal Society. If scientists have new research, they usually publish it in other journals. These include Proceedings of the Royal Society, Biology Letters, and Royal Society Open Science.

How the Journal Started and Grew

The Very Beginning of Philosophical Transactions

The first issue of the journal came out in London on March 6, 1665. This was about four and a half years after the Royal Society was created. The first editor and publisher was Henry Oldenburg. He was the Royal Society's first secretary. The full name Oldenburg gave the journal was quite long! It was Philosophical Transactions, Giving some Account of the present Undertakings, Studies, and Labours of the Ingenious in many considerable parts of the World.

The Royal Society's leaders agreed that Oldenburg could print the journal. He paid for it himself and kept any money it made. But the journal didn't make much money while he was alive. Oldenburg published 136 issues before he passed away in 1677.

Philosophical Transactions was the first to do many things that science journals still do today. It was the first to:

- Register (date and prove who wrote something).

- Certify (have other experts check the work, which is called peer review).

- Disseminate (share the information widely).

- Archive (keep a record of the work).

Oldenburg wanted the journal to be like a shared notebook for scientists. It helped share new ideas and discoveries that might not have been reported otherwise. At that time, printing was very controlled. There wasn't a "free press" like we have today. The first English newspaper, The London Gazette, came out later in the same year.

Oldenburg wrote many letters to scientists in other countries. This made some people think he was a spy! He was even put in the Tower of London in 1667. While he was locked up, someone else tried to publish a fake issue of the journal. But Oldenburg published the real one when he was released.

After Oldenburg died, the job of editor usually went to the Royal Society's secretary. They also paid for it themselves. For a short time, the journal's name was changed to Philosophical Collections. But it changed back in 1682.

The Eighteenth Century: A New Chapter

By the mid-1700s, important editors included Hans Sloane and Cromwell Mortimer. These editors were usually the Royal Society's secretaries. They also had to pay for the journal themselves.

Around 1750, some people criticized the journal. So, in 1752, the Royal Society decided to take over the journal officially. From then on, the journal was published "for the sole use and benefit of this Society." Members' fees would pay for it. A special group called the Committee of Papers would edit it.

The Royal Society paid for the paper, pictures, and printing. But the journal often lost money. It cost a lot to make, and they didn't sell many copies. This was because many copies were given away for free to members.

During the time of Joseph Banks, who was the President of the Royal Society, the journal kept running well. Publishing in Philosophical Transactions was a big honor.

The Nineteenth Century: Changes and Growth

The journal kept going strong into the 1800s. Around the 1820s and 1830s, people wanted to make the Royal Society better. They felt that too many non-scientists had joined. So, they pushed for experts to review papers for Transactions. This is how the idea of peer review became more common.

Special committees were set up to help decide which papers to publish. They would send papers to experts to review. This system helped improve the quality of the papers.

The cost of the journal kept going up, especially for illustrations. Pictures were a very important part of science journals. Engravings (pictures cut into metal) were used for detailed drawings. Wood cuts were used for diagrams.

By the mid-1850s, the journal was still costing the Royal Society a lot of money. The treasurer wanted to publish shorter papers and fewer of them. They printed 1000 copies of each issue. About 500 went to members for free. Authors also got many free copies to share. This meant not many copies were sold in stores.

George Gabriel Stokes was a secretary of the Royal Society for 31 years. He worked hard to make the review process more formal. During his time, authors could talk a lot with him about their papers.

In 1887, the Transactions officially split into two series: "A" for physical sciences and "B" for biological sciences. In 1897, the special committees were brought back. They helped manage the review process. Experts, usually members of the Royal Society, would review papers. This helped share the work of editing the journal.

The Twentieth Century: Modernizing the Journal

As time went on, authors were asked to submit their papers in a standard way. From 1896, they were encouraged to type their papers. This made it easier to get papers ready for printing and reduced mistakes. Papers now had to be presented clearly and be scientifically interesting.

After World War II, the journal finally started making money. This was partly because more universities and businesses started subscribing to it. By the 1970s, most of the journal's income came from these large organizations.

The journal also became more international. In 1973, only 11% of subscriptions were from the UK. Most were from the United States. However, most of the papers still came from British authors. The Royal Society wanted more scientists from other countries to submit papers. This finally happened in 1990.

By the end of the 1900s, the journal's editing became more professional. More staff were hired to help with editing, design, and marketing. The way papers were handled also changed. In 1997, Philosophical Transactions was first published online.

Amazing Scientists and Their Discoveries

Over the years, many huge scientific discoveries have been published in Philosophical Transactions. Here are some of the famous scientists who contributed:

| Isaac Newton | His first paper, New Theory about Light and Colours (1672), was a big step in his science career. |

| Anton van Leeuwenhoek | In 1677, Leeuwenhoek wrote about tiny living things he saw in water. This was the first detailed description of protists and bacteria. |

| Benjamin Franklin | This American statesman wrote or helped write 19 papers. One famous paper in 1753 was about his "Philadelphia Experiment" with an electrical kite. This experiment helped make him famous. |

| William Roy | In the 1780s, Major General William Roy measured the distance between observatories in Greenwich and Paris. This work helped create the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain, which makes detailed maps. |

| Caroline Herschel | In 1787, she became the first woman to publish in the journal. Her paper was about a new comet she found. She was paid to be an astronomer, which was very rare for women then. |

| Mary Somerville | She wrote about how ultraviolet light might magnetize steel. Even though her finding wasn't fully reproduced later, her idea was ahead of its time. |

| Charles Darwin | Darwin's only paper in this journal was about strange lines in Glen Roy, Scotland (1837). He thought they were from the sea. Later, he realized he was wrong and called it "one long gigantic blunder." |

| Michael Faraday | He published over 40 papers. His last paper in 1857 talked about tiny metal particles. Today, we call these nanoparticles. |

| James Clerk Maxwell | In 1865, Maxwell described how electricity and magnetism travel as waves. He figured out that light is an electromagnetic wave. |

| Kathleen Lonsdale | Her work on X-ray photography of crystals helped show how pure and perfect a crystal was. |

| Dorothy Hodgkin | She used special techniques to study proteins. Her work helped figure out the structures of things like Vitamin B-12 and insulin. |

| Alan Turing | Turing's 1952 paper, On the Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis, explored how chemicals create patterns in nature. He even created the term morphogen. |

| Stephen Hawking | His first paper in Philosophical Transactions was in 1983. It was about the universe's expansion. This paper came from a special meeting at the Royal Society. |

Public Access to the Journal

In 2011, a programmer named Greg Maxwell shared nearly 19,000 articles published before 1923. These articles were old enough to be in the public domain, meaning anyone could use them freely. They had been digitized by JSTOR but were behind a paywall.

Soon after, in August 2011, users uploaded over 18,500 of these articles to the Internet Archive. By November 2011, this collection was viewed 50,000 times a month!

In October 2011, the Royal Society made all its articles published before 1941 free to read. They said this decision was not because of Maxwell's actions.

In 2017, the Royal Society launched a new, high-quality digital version of the entire journal archive, going all the way back to 1665. All the old material that is out of copyright can be accessed for free without needing to log in.

See Also

- Journal des sçavans: This was the first academic journal ever. It started two months before Philosophical Transactions. However, it is not the longest-running because its publication stopped for 24 years. It covered science but also other subjects and mainly published book reviews.