Caroline Herschel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Caroline Herschel

|

|

|---|---|

|

.

Caroline Herschel at 78, one year after winning the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1828

|

|

| Born |

Caroline Lucretia Herschel

16 March 1750 |

| Died | 9 January 1848 (aged 97) Hanover, Kingdom of Hanover, German Confederation

|

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Discovery of several comets |

| Relatives | William Herschel (brother) |

| Awards | Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1828) Prussian Gold Medal for Science (1846) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

Caroline Lucretia Herschel (16 March 1750 – 9 January 1848) was a German-born British astronomer. She made huge contributions to astronomy, especially by discovering several comets. One of these, the periodic comet 35P/Herschel–Rigollet, is even named after her! She worked closely with her older brother, William Herschel, who was also a famous astronomer.

Caroline Herschel was a true pioneer for women in science. She was the first woman to earn a salary as a scientist and the first woman in England to hold a government job. She was also the first woman to publish scientific findings in a major journal called Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. In 1828, she became the first woman to win the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society. Later, in 1835, she was made an Honorary Member of the Royal Astronomical Society, along with Mary Somerville. She also became an honorary member of the Royal Irish Academy in 1838. When she turned 96 in 1846, the King of Prussia gave her a special Gold Medal for Science.

Contents

Early Life and Challenges

Caroline Lucretia Herschel was born in Hanover, Germany, on March 16, 1750. She was the eighth child of Issak Herschel, a musician who played the oboe, and Anna Ilse Moritzen. Her father was often away with his army regiment and became ill after a battle in 1743. He suffered from poor health for the rest of his life.

Caroline's older sister, Sophia, was much older and married when Caroline was only five. This meant Caroline had to do many of the household chores. She and her siblings received a basic education, learning to read and write. Her father tried to teach her more at home, but he had more success with her brothers.

When Caroline was ten, she got very sick with typhus. This illness stopped her from growing, so she never got taller than about 1.3 meters (4 feet 3 inches). She also lost some vision in her left eye. Her family thought she would never marry, and her mother believed it was best for her to train as a house servant instead of getting more education, which her father wanted for her. Sometimes, when her mother was away, her father would secretly teach her or include her in her brothers' lessons, like violin. She was briefly allowed to learn dress-making, but long hours of chores made it hard. To stop her from becoming a governess and earning her own money, she was even forbidden from learning French or advanced needlework.

After her father passed away, her brothers William and Alexander suggested she join them in Bath, England. William was a musician and wanted her to sing in his church performances. Caroline finally left Hanover on August 16, 1772, after her brother convinced their mother. On her journey to England, she first learned about astronomy by looking at the constellations and visiting shops that sold optical instruments.

In Bath, Caroline managed William's home and began singing lessons. William was a busy organist and music teacher. He also led the choir at the Octagon Chapel.

Caroline didn't make many friends in Bath, but she was finally able to learn. She took regular singing, English, and math lessons from William. She also learned to play the harpsichord. She became a key part of William's musical shows. She was the main singer at his concerts and became so good that she was offered a job at a music festival in Birmingham. However, she refused to sing for anyone but William. After that, her singing career slowed down because William wanted to spend more time on astronomy.

Becoming an Astronomer

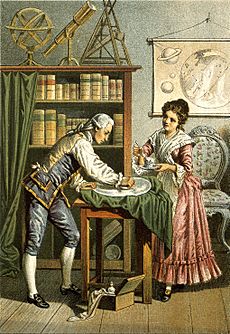

As William became more and more interested in astronomy, Caroline supported him again. She once said, "I did nothing for my brother but what a well-trained puppy dog would have done, that is to say, I did what he commanded me." But eventually, she grew to love astronomy and her work.

In the 1770s, William started building his own telescopes because he wasn't happy with the ones he could buy. Caroline would bring him food and read to him while he worked, even though she wanted to focus on her singing career.

She became an important astronomer herself because of her work with William. In March 1781, they moved to a new house. On March 13, William discovered the planet Uranus. He first thought it was a comet, but his discovery showed how good his new telescope was. Caroline and William gave their last music performance in 1782. William then became the court astronomer for King George III.

Astronomical Career

First Discoveries and Catalogues

William's interest in astronomy began as a hobby. Each morning, he would tell Caroline what he had learned the night before. Caroline became just as interested. She said her own work was "much hindered" because William always needed her help with his astronomy tools. William became famous for his powerful telescopes, and Caroline helped him a lot. She spent many hours polishing mirrors and setting up telescopes to collect as much light as possible. She also learned to copy astronomical lists and other books William borrowed. She learned to record, organize, and make sense of his observations. She knew this work needed to be fast, exact, and accurate.

In 1782, Caroline moved with William to Datchet, a small town near Windsor Castle. William expected her to be his assistant, a role she didn't like at first. She was unhappy with their rented house, which she called "the ruins of a place" because it had a leaky roof. While William worked on a list of 3,000 stars and studied double stars, Caroline was asked to "sweep" the sky. This meant carefully moving the telescope across the sky in strips to find interesting objects. She didn't like this task at first, missing the cultural life of Bath, but she slowly grew to love the work.

On August 28, 1782, Caroline started her first record book. She titled the first pages "This is what I call the Bills & Rec.ds of my Comets," "Comets and Letters," and "Books of Observations." These books are now kept at the Royal Astronomical Society in London.

On February 26, 1783, Caroline made her first discovery: a nebula (a cloud of gas and dust in space) that wasn't on any known list. That same night, she also found Messier 110 (NGC 205), which is the second companion galaxy to the Andromeda Galaxy. William then started looking for nebulae himself, realizing there were many new things to find. Caroline was often on a ladder, trying to measure double stars, which was very difficult. William soon realized his way of searching for nebulae was not efficient, and he needed an assistant to keep records. So, he asked Caroline.

In the summer of 1783, William built a special telescope for Caroline to search for comets, and she started using it right away. Starting in October 1783, the Herschels used a large 20-foot reflecting telescope to look for nebulae. At first, William tried to observe and record at the same time, but it was too hard. He again asked Caroline for help. She would sit by a window inside, William would shout his observations, and Caroline would write them down. This wasn't just simple copying. She had to use John Flamsteed's star catalogue to find the stars William used as reference points. Because Flamsteed's catalogue was organized by constellation, it wasn't very helpful for their work. So, Caroline created her own catalogue, organized by how far stars were from the North Star. The next morning, Caroline would review her notes and write formal observations, which she called "minding the heavens."

Discovering Comets

Between 1786 and 1797, Caroline discovered eight comets. She found the first one on August 1, 1786, while William was away and she was using his telescope. She was clearly the first to discover five of these comets and also found Comet Encke again in 1795. Five of her comet discoveries were published in the Philosophical Transactions journal. A collection of papers titled "This is what I call the Bills and Receipts of my Comets" contains information about each of these discoveries. William was even called to Windsor Castle to show Caroline's comet to the royal family. He called it "My Sister's Comet." Caroline Herschel is often said to be the first woman to discover a comet. However, Maria Margaretha Kirch discovered one in the early 1700s, but her discovery was often credited to her husband at the time.

Caroline wrote a letter to the Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne to announce her second comet. In December 1788, Maskelyne wrote back to congratulate her. She found her third comet on January 7, 1790, and her fourth on April 17, 1790. She told Sir Joseph Banks about both of these, and she found them all with her 1783 telescope. In 1791, Caroline started using a 9-inch telescope for her comet searches and found three more comets with it. Her fifth comet was found on December 15, 1791, and the sixth on October 7, 1795. Caroline wrote in her journal, "My brother wrote an account of it to Sir J. Banks, Dr. Maskelyne, and to several astronomical correspondents" for her fifth comet. Two years later, her eighth and last comet was discovered on August 6, 1797. This was the only comet she found without using a telescope. She announced this discovery by sending a letter to Banks. In 1787, King George III gave her an annual salary of £50 for her work as William's assistant. This made Caroline the first woman in England to have an official government job and the first woman to be paid for her work in astronomy.

In 1797, William's observations showed many mistakes in a star catalogue published by John Flamsteed. It was also hard to use because it was in two parts. William realized he needed a good way to cross-reference these differences but didn't want to spend time on it when he had more exciting astronomy to do. So, he asked Caroline to do it, which took her 20 months. The finished book, Catalogue of Stars, Taken from Mr. Flamsteed's Observations Contained in the Second Volume of the Historia Coelestis, and Not Inserted in the British Catalogue, was published by the Royal Society in 1798. It included an index of every observation Flamsteed made, a list of errors, and a list of over 560 stars that had been left out. In 1825, Caroline gave Flamsteed's works to the Royal Academy of Göttingen.

Working with William

Caroline often wrote about wanting to earn her own money and support herself. When the king started paying her in 1787, she became the first woman—at a time when even men rarely got paid for science—to receive a salary for scientific work. Her salary was £50 a year, and it was the first money Caroline had ever earned on her own.

When William married Mary Pitt in 1788, it caused some tension between Caroline and her brother. Some people have described Caroline as being jealous.

However, historian Richard Holmes explains that the marriage changed things for Caroline in many ways. She lost her role in managing the household and her social standing. She also moved out of the house and into separate rooms, coming back daily to work with William. She no longer had the keys to the observatory and workroom where she did much of her own work. We don't know all her feelings about this time because she destroyed her journals from 1788 to 1798. But in August 1799, Caroline was recognized for her work independently when she spent a week in Greenwich as a guest of the royal family.

Despite these changes, she and her brother continued to work well together. When William and his family were away, Caroline often took care of their home. Later in life, she and William's wife exchanged kind letters, and Caroline became very close to her nephew, the astronomer John Herschel.

William's marriage likely helped Caroline become more independent and famous in her own right. Caroline made many discoveries on her own and continued to work on many astronomy projects that helped her become well-known.

New General Catalogue

In 1802, the Royal Society published Caroline's catalogue in its Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, but under William's name. This list added about 500 new nebulae and star clusters to the 2,000 already known.

Towards the end of Caroline's life, she organized 2,500 nebulae and star clusters by their polar distances. This helped her nephew, John Herschel, study them in an organized way. This list was later made bigger and renamed the New General Catalogue. Many objects in space are still known by their NGC number today.

Later Life and Legacy

After her brother William died in 1822, Caroline was very sad and moved back to Hanover, Germany. She continued her astronomy studies there, checking William's findings and creating a catalogue of nebulae to help her nephew John Herschel. However, buildings in Hanover made it hard for her to observe the sky, so she spent most of her time working on the catalogue. In 1828, the Royal Astronomical Society gave her their Gold Medal for this work. No other woman would receive this award until Vera Rubin in 1996. After William's death, her nephew, John Herschel, took over observing at Slough. Caroline had first introduced him to astronomy by showing him the constellations in Flamsteed's Atlas. Caroline made her last entry in her observing book on January 31, 1824, about the Great Comet of 1823, which had been discovered earlier on December 29, 1823. In her later years, Caroline remained active and healthy. She often met with other famous scientists. She spent her last years writing her memories and wishing her body could still let her make new discoveries.

Caroline Herschel passed away peacefully in Hanover on January 9, 1848. She is buried in Hanover next to her parents. Her tombstone says, "The eyes of her who is glorified here below turned to the starry heavens." With her brother, she discovered over 2,400 astronomical objects in twenty years. The asteroid 281 Lucretia (found in 1888) was named after Caroline's middle name, and the crater C. Herschel on the Moon is named after her.

The 1968 poem "Planetarium" by Adrienne Rich celebrates Caroline Herschel's life and scientific achievements. In Judy Chicago's 1969 artwork The Dinner Party, which honors important historical women, there is a place setting for Caroline Herschel. Google also honored her with a Google Doodle on her 266th birthday on March 16, 2016.

Honours and Recognition

Caroline Herschel was honored by the King of Prussia and the Royal Astronomical Society. She received the gold medal from the Astronomical Society in 1828 for her work on the 2,500 nebulae discovered by her brother. This work was seen as a huge achievement in astronomy. She finished this important work after her brother died and she moved back to Hanover.

The Royal Astronomical Society made her an Honorary Member in 1835, along with Mary Somerville. They were the first women to become members. She was also made an honorary member of the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin in 1838.

In 1846, when she was 96 years old, the King of Prussia gave her a Gold Medal for Science. This was given to her by Alexander von Humboldt, who said it was "in recognition of the valuable services rendered to Astronomy by you, as the fellow-worker of your immortal brother, Sir William Herschel, by discoveries, observations, and laborious calculations."

The asteroid 281 Lucretia is named in her honor.

The open clusters NGC 2360 (Caroline's Cluster) and NGC 7789 (Caroline's Rose) are unofficially nicknamed after her.

On November 6, 2020, a satellite named after her (ÑuSat 10 or "Caroline") was launched into space.

In 2022, the Herschel Museum in Bath got a handwritten draft of Caroline Herschel’s memoirs. These will be shown in 2023.

See also

In Spanish: Carolina Herschel para niños

In Spanish: Carolina Herschel para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |