Maria Margaretha Kirch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Maria Margaretha Kirch

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Maria Margaretha Winkelmann

25 February 1670 Panitzsch near Leipzig, Electorate of Saxony

|

| Died | 29 December 1720 (aged 50) |

| Nationality | German |

| Awards | Gold medal of Royal Academy of Sciences, Berlin (1709) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics and Astronomy |

Maria Margaretha Kirch (born Winckelmann) was a German astronomer. She lived from 1670 to 1720. Maria was one of the first well-known female astronomers. She became famous for her writings about planets. She wrote about the Sun joining with Saturn and Venus in 1709. Later, she wrote about Jupiter and Saturn in 1712.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Maria's father was a Lutheran minister. He believed girls should get the same education as boys. So, he taught her from a young age. By the time she was 13, both her parents had passed away.

She continued her learning with her brother-in-law. She also learned from Christoph Arnold, a famous astronomer. He lived nearby and was known for finding a comet. Maria became Arnold's unofficial helper and later his assistant. She even lived with his family. Back then, becoming an astronomer was not like joining a formal school. People learned in different ways.

Meeting Gottfried Kirch

Through Arnold, Maria met Gottfried Kirch. He was a well-known German astronomer and mathematician. He was 30 years older than Maria. Gottfried had learned astronomy from Johannes Hevelius and studied at the University of Jena.

Maria and Gottfried married in 1692. They had four children. All their children later studied astronomy, just like their parents. Maria helped Gottfried with his work. She did calculations and collected data. In return, she could continue her own astronomy studies. Without their marriage, it would have been hard for Maria to work in astronomy on her own.

In 1700, the family moved to Berlin. This was because Gottfried Kirch was made the Astronomer Royal. This important job was given by Frederick III, the ruler of Brandenburg.

Working as an Astronomer

Women were not allowed to attend universities in Germany at this time. But this did not stop them from studying the stars. Most astronomy work happened outside universities. Many astronomers did not have special degrees in astronomy. They often had degrees in medicine, law, or religion.

Maria Kirch became one of the few women working in astronomy in the 1700s. She was often called Kirchin, which was the female version of her family name. Other women astronomers in the Holy Roman Empire included Maria Cunitz, Elisabeth Hevelius, and Maria Clara Eimmart.

Making Calendars

Frederick III, the ruler, started a monopoly on calendars. This meant only certain people could make and sell them. The money from calendar sales helped pay astronomers. It also supported the members of the Berlin Academy of Sciences. Frederick III started this Academy in 1700. He also built an observatory which opened in 1711.

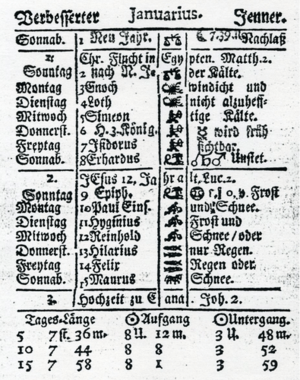

Gottfried Kirch, with Maria's help, created the first calendar for this new system. It was called Chur-Brandenburgischer Verbesserter Calender Auff das Jahr Christi 1701. It became very popular.

Maria and Gottfried worked as a team. Maria moved from being Arnold's helper to assisting her husband. She was his unofficial but recognized assistant at the Academy. Together, they watched the sky and did calculations. They used this information to create calendars and ephemerides (tables showing where planets would be).

From 1697, the Kirchs also started recording weather information. Their data was used for calendars and almanacs. It was also very helpful for navigation. The Berlin Academy of Sciences sold their calendars.

Discovering a Comet

For ten years, Maria worked as her husband's assistant at the Academy. Every evening, she would observe the sky starting at 9 p.m. During one of these regular observations, she found a comet.

On April 21, 1702, Maria Kirch discovered the "Comet of 1702". Today, everyone agrees that Maria found it first. However, at the time, her husband was given credit for the discovery. In his notes from that night, Gottfried wrote:

"Early in the morning (about 2:00 AM) the sky was clear and starry. Some nights before, I had observed a variable star and my wife (as I slept) wanted to find and see it for herself. In so doing, she found a comet in the sky. At which time she woke me, and I found that it was indeed a comet... I was surprised that I had not seen it the night before".

This comet was actually seen a day earlier by two astronomers in Rome, Italy.

Maria's Publications

Germany's only science journal at the time, Acta Eruditorum, was in Latin. Maria Kirch's later writings were all in German. She published them under her own name.

Maria and Gottfried often observed the sky together. He would watch the north, and she would watch the south. This allowed them to make more accurate observations than one person could.

Maria continued her astronomy work. She published her findings in German, with her own name on them. Her important contributions to astronomy include:

- Observations on the Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights) in 1707.

- A pamphlet called Von der Conjunction der Sonne des Saturni und der Venus in 1709. This was about the Sun joining with Saturn and Venus.

- A publication about the upcoming meeting of Jupiter and Saturn in 1712.

Before Maria Kirch, Maria Cunitz was the only female astronomer in the Holy Roman Empire to publish under her own name. Alphonse des Vignoles, a family friend, praised Maria Kirch. He said that women are capable of great things in science, especially astronomy.

Meeting the Prussian Court

In 1709, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the president of the Berlin Academy of Sciences, introduced Maria to the Prussian court. There, Maria explained her observations of sunspots. Leibniz said about her:

"There is a most learned woman who could pass as a rarity. Her achievement is not in literature or rhetoric but in the most profound doctrines of astronomy... I do not believe that this woman easily finds her equal in the science in which she excels... She favors the Copernican system (the idea that the sun is at rest) like all the learned astronomers of our time. And it is a pleasure to hear her defend that system through the Holy Scripture in which she is also very learned. She observes with the best observers and knows how to handle marvelously the quadrant and the telescope."

Challenges and Later Work

After her husband Gottfried died in 1710, Maria Kirch tried to take his place. She wanted to become the official astronomer and calendar maker at the Royal Academy of Sciences. In the past, it was common for widows to take over their husband's jobs.

Leibniz, the Academy president, supported her request. However, the Academy's council said no. They worried that allowing a woman to take an official position would set a new example. They did not want to create a precedent. Even though about 14% of astronomers in the early 1700s were women, it was still rare for women to join scientific academies.

Maria explained her skills in her application. She said her husband had taught her well in astronomy. She had worked in astronomy since her marriage. She had also worked at the Academy for ten years. Maria even mentioned that she had prepared the calendar under her husband's name when he was sick. For Maria, this job was not just an honor. It was also a way to support herself and her children. She explained that her husband had not left her with enough money.

In the old guild system, Maria could have taken over her husband's job. But the new science academies did not follow those old traditions. Maria and Gottfried had both spent years working on calendars and discovering comets. But Maria did not have a university education, which most Academy members had.

Leibniz was the only important person who supported Maria. Sadly, negative opinions about her gender were stronger than her excellent work. The Academy secretary, Johann Theodor Jablonski, warned Leibniz against hiring her. He said, "If she were now to be kept on in such a capacity, mouths would gape even wider." The Academy was worried about its reputation.

Maria's application was rejected. Leibniz tried to get her housing and a salary in 1711. He got her housing, but the Academy still refused to pay her. Later in 1711, the Academy did give Maria a medal for her astronomy work. Maria kept trying to join the Berlin Academy for over a year. But after Leibniz left Berlin in 1711, the Academy refused her even more strongly. She received her final rejection in early 1712.

Maria believed her gender was the reason for the rejections. Instead of her, Johann Heinrich Hoffmann was given her husband's job. He had little experience. Hoffmann soon fell behind in his work. He failed to make the required observations. Some even suggested Maria become his assistant. Maria wrote, "Now I go through a severe desert, and because... water is scarce... the taste is bitter."

New Opportunities

In 1711, Maria published Die Vorbereitung zug grossen Opposition. This popular pamphlet predicted a new comet. She followed it with another pamphlet about Jupiter and Saturn.

In 1712, Maria accepted an offer from Bernhard Friedrich von Krosigk. He was a keen amateur astronomer. Maria started working at his observatory. She and her husband had worked there before, while the Academy observatory was being built. At Krosigk's observatory, Maria became a "master" astronomer.

After Baron von Krosigk died in 1714, Maria moved to Danzig for a short time. She helped a mathematics professor there. Then she returned to Berlin in 1716. Maria and her son, who had just finished university, received an offer. They were asked to work for the Russian czar Peter the Great. But they chose to stay in Berlin. Maria continued to calculate calendars from her home. She made calendars for cities like Nuremberg, Dresden, Breslau, and Hungary.

Maria had trained her son Christfried Kirch and daughters Christine Kirch and Margaretha Kirch. They helped her with the family's astronomy work. They continued to make calendars and almanacs. They also made observations.

In 1716, her son Christfried and Johann Wilhelm Wagner became observers at the Academy observatory. This happened after Hoffmann's death. Maria moved back to Berlin to help her son. Her daughter Christine also helped. Maria was again working at the Academy observatory, calculating calendars.

However, male Academy members complained. They felt Maria was too involved and "too visible at the observatory when strangers visit." Maria was told to "retire to the background and leave the talking to... her son." In 1717, the Berlin Academy gave Maria two choices. She could keep fighting for her own position, or she could retire. They said retiring would help her son's reputation. She chose to retire and continued her observations at home. The Academy asked her to live nearby so her son could still eat at home.

Maria Kirch died of a fever in Berlin on December 29, 1720.

See also

In Spanish: Maria Winkelmann para niños

In Spanish: Maria Winkelmann para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |