Women in science facts for kids

Women in science have always been important throughout history, making many great discoveries. People interested in how gender affects science have studied what women have done, the challenges they faced, and how they got their work recognized. This study has become a field of its own.

Women were involved in medicine in early civilizations. In ancient Greece, women could study natural philosophy (which was like early science). Women also helped with alchemy (an early form of chemistry) around the 1st or 2nd centuries CE. During the Middle Ages, religious convents were key places for women to learn and even do research. However, when the first universities started in the 11th century, women were mostly kept out.

Later, botany (the study of plants) was a science where women made many contributions. Italy was more open to women in medicine than other places. The first known woman to become a university professor in science was Laura Bassi in the 1700s.

In the 18th century, women started making big steps in science, even though society often limited their roles. By the 19th century, women were still mostly excluded from formal science education, but they began joining scientific groups. The rise of women's colleges later in the 19th century created jobs and learning chances for female scientists. Marie Curie was a pioneer, studying radioactive decay and discovering the elements radium and polonium. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in Physics and the first person to win a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Between 1901 and 2022, 60 women have won Nobel Prizes, with 24 in physics, chemistry, or medicine.

Contents

Science Around the World

In the 1970s and 1980s, many books about women scientists came out. But most of them only focused on women from Europe and North America. Organizations like the Kovalevskaia Fund (started in 1985) and the Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World (1993) helped show the work of women scientists from other parts of the world.

Even today, we don't have much information about women in science in developing countries. As academic Ann Hibner Koblitz said, people often assume that what's true for women in science in the West is true everywhere. But this isn't always the case. For example, engineering is often seen as a job for men in many countries. But in the former Soviet Union, many women were engineers. In Nicaragua in 1990, 70% of engineering students were women! This shows that what is considered a "woman's field" can change a lot from one country or time period to another.

Women in Science Through History

Ancient Times

Women have been involved in medicine since ancient times. Peseshet, an Egyptian doctor from around 2600–2500 BCE, is the earliest known female doctor mentioned in history. She was called "lady overseer of the female physicians." In ancient Greece, Agamede was known as a healer. Later, Agnodice was said to be the first female doctor to practice legally in Athens.

Women in ancient Greece also studied natural philosophy. Aglaonike predicted eclipses, and Theano was a mathematician and doctor. She was part of a school founded by Pythagoras that included many women.

Around 1200 BCE in Babylonia, two perfumers, Tapputi-Belatekallim and -ninu, used extraction and distillation to get essences from plants. In ancient Egypt, women used chemistry to make beer and medicines. Women also made big contributions to alchemy, especially in Alexandria around the 1st or 2nd centuries CE. The most famous female alchemist, Mary the Jewess, invented several chemical tools, like the double boiler (bain-marie).

Hypatia of Alexandria (around 350–415 CE) was a philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer. She is the earliest female mathematician we know a lot about. Hypatia wrote important comments on geometry, algebra, and astronomy. She led a school and taught many students. Sadly, she was killed in 415 CE due to a political fight.

Medieval Europe

The early Middle Ages in Europe were tough times for learning after the Roman Empire fell. But the Arabic world kept science alive and copied old writings. During this time, Christianity grew, and monasteries and nunneries became important places for education. Monks and nuns copied old texts and helped keep knowledge alive.

As mentioned, convents were key for women's education. They helped women learn to read and write, and some even allowed women to do scholarly research. A great example is the German abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179 AD). She was a famous philosopher and botanist who wrote a lot about science, medicine, and natural history. Another abbess, Hroswitha of Gandersheim (935–1000 AD), also encouraged women to be thinkers.

However, as nunneries grew, the male church leaders didn't like it. They pushed back against women's progress, closing many religious orders for women. This limited women's chances to learn and their influence in science.

When the first universities appeared in the 11th century, women were mostly not allowed to attend. But there were some exceptions. The University of Bologna in Italy, founded in 1088, let women attend classes from the start.

Italy seemed more open to women in medicine. Trotula of Salerno, a physician, is thought to have taught at the Medical School of Salerno in the 11th century. She taught many noble Italian women, sometimes called the "ladies of Salerno." She also wrote important books on women's medicine, including obstetrics (childbirth) and gynecology (women's health).

Dorotea Bucca was another famous Italian doctor. She taught philosophy and medicine at the University of Bologna for over 40 years starting in 1390. Other Italian women who contributed to medicine included Abella, Jacobina Félicie, and Alessandra Giliani.

Despite these successes, society often held women back. For example, the Christian scholar Thomas Aquinas wrote that women were "mentally incapable of holding a position of authority."

Scientific Revolutions of the 1600s and 1700s

Margaret Cavendish, a noblewoman in the 1600s, joined in big science discussions. She wasn't allowed to join the English Royal Society, but she did attend a meeting once. She wrote books on science, like Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. In her writings, she questioned the idea that humans could completely control nature through science. She also tried to get more women interested in science.

Isabella Cortese, an Italian alchemist, was known for her book The Secrets of Isabella Cortese. She wrote about creating medicines, alchemy, and cosmetics. Her book was popular among wealthy people in the 1500s, and many of its "secrets" were for women, including topics like pregnancy.

Sophia Brahe from Denmark was a gardener and astronomer. Her brother, Tycho Brahe, taught her chemistry and gardening, and she learned astronomy by herself. She helped her brother with his work and made observations that led to the discovery of a supernova (a new star).

In Germany, some women became astronomers because of their skills in craft production. Between 1650 and 1710, 14% of German astronomers were women. The most famous was Maria Winkelmann. She learned astronomy from her father and uncle. When she married Gottfried Kirch, a leading astronomer, she became his assistant. She even discovered a comet! But after her husband died, she was denied a job at the Berlin Academy because she was a woman and didn't have a university degree. They worried about setting a "bad example."

Winkelmann's story shows the challenges women faced. No woman was invited to the Royal Society of London or the French Academy of Sciences until the 20th century. Most people in the 17th century thought women should focus on home duties, not scholarly work.

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) was a German scientist who studied nature. From age 13, she raised caterpillars and watched them turn into butterflies. She published a book with her drawings of plants and insects. She even traveled to South America to study insects, birds, and reptiles. She was a botanist and entomologist known for her amazing illustrations.

Overall, the Scientific Revolution didn't really change ideas about women's ability to do science. Some male scientists even used new science to say that women were naturally weaker and should stay at home.

The 1700s: A Time of Change

The 1700s had different ideas about women: some thought they were less capable, some thought they were equal but different, and some thought they could be equal in mind and contributions. The Enlightenment period, however, saw women take on bigger roles in science.

Salons (social gatherings) in Europe brought thinkers together to discuss politics, society, and science. Women often hosted and participated in these discussions.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu bravely introduced smallpox inoculation (a way to prevent the disease) to Western medicine. She saw it in the Ottoman Empire and had her own children inoculated in England. She even convinced the Princess to test it on prisoners.

Laura Bassi earned a doctorate in philosophy in 1732 from the University of Bologna. She was the second woman in the world to get a philosophy doctorate. She then became the first woman to be a physics professor at a European university. She gave private lessons and experiments from home, and her salary was the highest paid by the university.

Maria Gaetana Agnesi is considered the first woman in the Western world to be famous in mathematics. She wrote the first mathematics handbook for young Italian students in 1748. It was seen as the best introduction to the works of Leonhard Euler. She also became a professor at the University of Bologna, but she never taught there.

Dorothea Erxleben from Germany was taught medicine by her father. Inspired by Laura Bassi, she fought for her right to practice medicine. In 1742, she wrote that women should be allowed to go to university. With special permission, she earned her medical degree in 1754, becoming the first female doctor in Germany. She also wrote about the challenges women faced, like housework and children.

In Sweden, Charlotta Frölich was the first woman published by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1741–42, with books on farming. In 1748, Eva Ekeblad became the first woman in that academy. She discovered how to make flour and alcohol from potatoes, which helped improve food supply in Sweden. She also found ways to bleach cotton and use potato flour in cosmetics.

Émilie du Châtelet, a friend of Voltaire, was the first scientist to understand the importance of kinetic energy (energy of motion). She showed that the impact of falling objects depends on their speed squared. This was a huge step for Newtonian mechanics. She also translated Newton's famous book, Principia, into French, adding her own ideas about conservation of energy. Her work helped complete the scientific revolution in France.

Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze and her husband Antoine Lavoisier transformed chemistry. Paulze helped Lavoisier in his lab, taking notes and drawing his experiments. She translated important works and even pointed out errors in other chemists' ideas. She was key to the 1789 publication of Lavoisier's Elementary Treatise on Chemistry, which introduced the idea of conservation of mass and a new system for naming chemicals.

The astronomer Caroline Herschel moved from Germany to England and worked as an assistant to her brother, William Herschel. In 1787, she became the first woman to be paid for her science work. She discovered eight comets between 1786 and 1797. Her brother showed her comet to the royal family. While Caroline is often credited as the first woman to discover a comet, Maria Kirch discovered one earlier but it was credited to her husband.

The 1800s: Growing Opportunities

Early 1800s

Science was still mostly a hobby in the early 1800s. Botany was popular and seen as a good activity for women. It was one of the easiest sciences for women to get into in England and North America.

However, as science became more professional, women were often excluded from formal education. But their contributions started to be recognized as they were sometimes allowed into scientific societies.

Mary Fairfax Somerville from Scotland did experiments in magnetism. She presented a paper to the Royal Society in 1826, being the second woman to do so. She also wrote many books on math, astronomy, and geography, and strongly supported women's education. In 1835, she and Caroline Herschel were the first two women to become honorary members of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Ada Lovelace, an English mathematician and student of Somerville, worked with Charles Babbage on his analytical engine (an early computer). In her notes, she imagined how it could be used for more than just math, like composing music. She is sometimes called the first computer programmer.

In Germany, schools for women's "higher" education were founded. The Deaconess Institute in Kaiserswerth, established in 1836, trained women in nursing. Florence Nightingale later studied there.

In the US, Maria Mitchell became famous for discovering a comet in 1847. She also helped calculate data for the Nautical Almanac. She was the first woman to join the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1848.

Other important female scientists of this time include:

- In Britain: Mary Anning (paleontologist), Anna Atkins (botanist), Janet Taylor (astronomer)

- In France: Marie-Sophie Germain (mathematician), Jeanne Villepreux-Power (marine biologist)

Late 1800s in Western Europe

The late 19th century brought more educational chances for women. New schools for girls opened in the UK, like the North London Collegiate School (1850). The first women's university colleges, like Girton (1869), also started.

The Crimean War (1854–6) helped establish nursing as a respected job, making Florence Nightingale famous. She set up a nursing school in London in 1860 and was also a pioneer in public health and statistics.

James Barry was the first British woman to get a medical degree in 1812, by pretending to be a man. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was the first openly female British doctor in 1865. With others, she founded the first UK medical school for women, the London School of Medicine for Women, in 1874.

Annie Scott Dill Maunder was a pioneer in astronomical photography, especially of sunspots. She worked with her husband, Edward Walter Maunder, at the Greenwich Observatory. She helped analyze sunspot data and designed a special camera. In 1898, she took the first photos of the sun's corona during an eclipse in India. Their work showed that specific sun regions caused geomagnetic storms.

In Prussia, women could go to university from 1894 and get PhDs. By 1908, all limits for women in universities were removed.

Late 1800s in Russia

In the late 19th century, many successful women in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) were Russian. Since women were often blocked from science fields in Russia, many went to Western Europe, especially Switzerland, to study. These "women of the sixties" (шестидесятницы) were pioneers in higher education for women in Europe. They were often the first female students and earned the first doctorates in medicine, chemistry, math, and biology.

Notable Russian scientists included:

- Nadezhda Suslova (1843–1918): The first woman in the world to get a medical doctorate equal to men's degrees.

- Iulia Lermontova (1846–1919): The first woman in the world to get a chemistry doctorate.

- Sofia Kovalevskaia (1850–1891): The first woman in 19th-century Europe to get a math doctorate and become a university professor.

Late 1800s in the United States

The growth of women's colleges in the late 19th century created jobs and education chances for women scientists. These colleges produced many women who went on to earn PhDs in science. Many coeducational colleges also started admitting women.

Elizabeth Blackwell became the first certified female doctor in the US in 1849. With her sister, Emily Blackwell, she founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in 1857. This provided training and experience for women doctors.

In 1876, Elizabeth Bragg became the first woman to graduate with a civil engineering degree in the US from the University of California, Berkeley.

Early 1900s

Europe Before World War II

Marie Skłodowska-Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in 1903 (physics). She then won a second Nobel Prize in 1911 (chemistry) for her work on radiation. She was the first person to win two Nobel Prizes and the first woman to teach at Sorbonne University in Paris.

Alice Perry was the first woman to get a civil engineering degree in the UK in 1906.

Lise Meitner was key in discovering nuclear fission (splitting atoms). She worked with Otto Hahn in Berlin until she had to flee in 1938. In 1939, with her nephew Otto Frisch, Meitner explained the theory behind an experiment that showed nuclear fission.

Maria Montessori was the first woman in Southern Europe to become a doctor. She became interested in children's diseases and believed in educating children with special needs. She developed a teaching method, now called Montessori education, which focuses on educating the senses first, then the intellect.

Emmy Noether made big changes in abstract algebra and helped fill gaps in relativity. She is famous for Noether's theorem, which explains conservation laws in physics. She was not allowed to present her own paper in 1918 because she was a woman.

Mary Cartwright was a British mathematician who studied chaotic systems. Inge Lehmann, a Danish seismologist, suggested in 1936 that Earth's molten core has a solid inner core. Joan Beauchamp Procter was the first female Curator of Reptiles at the London Zoo.

Florence Sabin was an American medical scientist. She was the first woman faculty member at Johns Hopkins in 1902 and the first full-time female professor there in 1917. She published over 100 scientific papers.

United States Before and During World War II

By 1900, many women entered science, helped by women's colleges and new universities. Margaret W. Rossiter's books show how women found opportunities in science during this time.

In 1892, Ellen Swallow Richards proposed a new science called "oekology" (ecology). This included studying "consumer nutrition" and environmental education. This field later split into modern ecology and home economics, which gave women another path to study science. Richards also started the first biology course at MIT.

Women also found opportunities in botany and embryology. In psychology, women earned doctorates but often worked in educational or child psychology in hospitals or social agencies.

In 1901, Annie Jump Cannon realized that a star's temperature was the main feature distinguishing different spectra. Her work led to the modern classification of stars (O, B, A, F, G, K, M).

Henrietta Swan Leavitt published her study of variable stars in 1908. This led to the "period-luminosity relationship" of Cepheid variables. This discovery changed our understanding of the universe's size. Famous astronomer Edwin Hubble often said Leavitt deserved the Nobel Prize for her work.

In 1925, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin showed that stars are made almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, a key theory in astrophysics.

Canadian-born Maud Menten worked in the US and Germany. Her most famous work was on enzyme kinetics, which describes how enzymes work. She also invented a method for detecting an enzyme called alkaline phosphatase, still used today.

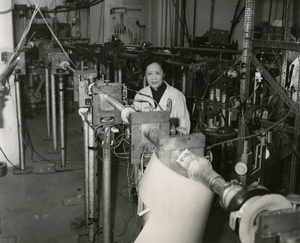

World War II created new opportunities for women in science. The Office of Scientific Research and Development kept a list of trained scientists, including women. Due to worker shortages, some women got jobs they might not have otherwise. Many women worked on the Manhattan Project (to develop the atomic bomb). These included Leona Woods Marshall, Katharine Way, and Chien-Shiung Wu. Wu confirmed that Xe-135 was stopping the B reactor from working, which helped the project continue.

Wu later confirmed Einstein's EPR Paradox and proved the first violation of Parity and Charge Conjugate Symmetry, which was important for the future of Particle Physics.

Women in other fields also helped the war effort. Three nutritionists, Lydia J. Roberts, Hazel K. Stiebeling, and Helen S. Mitchell, created the Recommended Dietary Allowance in 1941 to help plan meals for military and civilians, especially when food was rationed. Rachel Carson worked for the US Bureau of Fisheries, writing about fish and helping the Navy develop ways to detect submarines.

Women in psychology formed the National Council of Women Psychologists to help with the war. In social sciences, women like Dorothy Swaine Thomas and Tamie Tsuchiyama contributed to a study on the Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement.

In the United States Navy, female scientists did a lot of research. Mary Sears, a planktonologist, led the Oceanographic Unit. Florence van Straten, a chemist, studied how weather affected combat. Grace Hopper, a mathematician, became one of the first computer programmers for the Harvard Mark I computer. Mina Spiegel Rees, also a mathematician, was a chief technical aide for the National Defense Research Committee.

Gerty Cori was a biochemist who discovered how glycogen (a form of sugar) is used for energy in muscles. She won the Nobel Prize in 1947, becoming the third woman and first American woman to win a Nobel Prize in science. She was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Late 1900s to Early 2000s

Nina Byers noted that before 1976, women's important contributions to physics were rarely recognized. Women often worked without pay or in jobs that didn't match their skills. This is slowly changing.

In the early 1980s, Margaret Rossiter described "hierarchical segregation" (fewer women at higher ranks) and "territorial segregation" (women grouping in certain science fields).

A recent book, Athena Unbound, looks at women in science from childhood to their careers. It says that women still face special barriers to success in science, even with recent progress.

The L'Oréal-UNESCO Awards for Women in Science started in 1998. They give prizes to women scientists from different regions each year. By 2017, almost 100 women from 30 countries had been recognized. Two winners, Ada Yonath and Elizabeth Blackburn, later won Nobel Prizes.

Europe After World War II

Tikvah Alper (1909–95), a physicist and radiobiologist working in the UK, made key discoveries about biological processes.

French virologist Françoise Barré-Sinoussi helped identify the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS. She shared the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work.

In 1967, Jocelyn Bell Burnell found evidence for the first known radio pulsar. Her supervisor received the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery.

Astrophysicist Margaret Burbidge helped create the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis, which explains how elements are formed in stars. She held important positions, including director of the Royal Greenwich Observatory.

Mary Cartwright was a mathematician whose work on nonlinear differential equations was important for dynamical systems.

Rosalind Franklin was a crystallographer. Her work helped show the structure of coal, graphite, DNA, and viruses. Her DNA work in 1953 helped Watson and Crick figure out the structure of DNA. They won the Nobel Prize without fully crediting Franklin, who had died of cancer in 1958.

Jane Goodall is a British primatologist and a world expert on chimpanzees. She is famous for her over 55-year study of wild chimpanzees' social and family lives.

Dorothy Hodgkin studied the molecular structure of complex chemicals using X-rays. She won the 1964 Nobel Prize for chemistry for finding the structure of vitamin B12.

Irène Joliot-Curie, Marie Curie's daughter, won the 1935 Nobel Prize for chemistry with her husband for their work on radioactive isotopes. This made the Curies the family with the most Nobel winners.

Palaeoanthropologist Mary Leakey discovered the first skull of a fossil ape and a robust Australopithecine.

Italian neurologist Rita Levi-Montalcini won the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering Nerve growth factor (NGF). Her work helped understand diseases like tumors. She was also active in politics and became a Senator for Life in Italy.

Zoologist Anne McLaren studied genetics, leading to advances in in vitro fertilization. She was the first female officer of the Royal Society in 331 years.

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1995 for her research on how genes control embryonic development. She also started a foundation to help young German female scientists with children.

United States After World War II

Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Fran Bilas, and Ruth Lichterman were six of the first programmers for the ENIAC, the first general-purpose electronic computer.

Linda B. Buck is a neurobiologist who shared the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her work on olfactory receptors (smell).

Rachel Carson was a marine biologist and is seen as the founder of the environmental movement. Her 1962 book, Silent Spring, warned about the dangers of pesticides. This led to questions about harmful chemicals and eventually to the banning of DDT.

Eugenie Clark, known as The Shark Lady, was an American ichthyologist famous for her research on poisonous fish and shark behavior.

Ann Druyan is an American writer and producer who specializes in cosmology and popular science. She helped select music for the Voyager Golden Record on the Voyager space missions.

Gertrude B. Elion was an American biochemist and pharmacologist. She won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1988 for her work on differences between normal human cells and disease-causing cells.

Sandra Moore Faber, with Robert Jackson, discovered the Faber–Jackson relation for elliptical galaxies. She also led the team that found the Great Attractor, a huge concentration of mass pulling nearby galaxies.

Zoologist Dian Fossey worked with gorillas in Africa from 1967 until her death in 1985.

Astronomer Andrea Ghez received a "genius grant" in 2008 for her work improving earthbound telescopes.

Maria Goeppert Mayer was the second female Nobel Prize winner in Physics. She proposed the nuclear shell model of the atomic nucleus. Earlier in her career, she worked in unpaid positions.

Sulamith Low Goldhaber and her husband formed a research team on high-energy particles in the 1950s.

Carol Greider and Elizabeth Blackburn, with Jack W. Szostak, received the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering how chromosomes are protected by telomeres and the enzyme telomerase.

Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper developed the first computer compiler in 1952.

Deborah S. Jin's team in 2003 created the first fermionic condensate, a new state of matter.

Stephanie Kwolek, a researcher at DuPont, invented Kevlar, a very strong material.

Lynn Margulis is a biologist known for her endosymbiotic theory, which explains how certain cell parts were formed.

Barbara McClintock's studies of maize genetics showed genetic transposition in the 1940s and 1950s. She received her PhD in 1927. Her discovery helped us understand how genes can move on chromosomes. She won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983, becoming the first American woman to win a Nobel Prize alone.

Nita Ahuja is a famous surgeon-scientist known for her work on cancer. She is the first woman to be the Chief of Surgical Oncology at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Carolyn Porco is a planetary scientist known for her work on the Voyager program and the Cassini–Huygens mission to Saturn. She also helps make science popular.

Physicist Helen Quinn, with Roberto Peccei, suggested Peccei-Quinn symmetry. This led to the idea of a particle called the axion, which might be dark matter. Quinn was the first woman to receive the Dirac Medal.

Lisa Randall is a theoretical physicist and cosmologist, known for her Randall–Sundrum model. She was the first tenured female physics professor at Princeton University.

Sally Ride was an astrophysicist and the first American woman to travel to space. She wrote books for children to encourage them to study science. She also worked on the Gravity Probe B project, which supported Albert Einstein's theory of relativity.

Astronomer Vera Rubin discovered the Galaxy rotation problem by observing galaxy rotation curves. This is key evidence for dark matter. She was the first woman allowed to observe at the Palomar Observatory.

Sara Seager is a Canadian-American astronomer known for her work on extrasolar planets.

Astronomer Jill Tarter is known for her work on the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI). She was named one of the 100 most influential people by Time Magazine in 2004.

Rosalyn Yalow shared the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for developing the radioimmunoassay (RIA) technique.

Australia After World War II

- Amanda Barnard: A theoretical physicist specializing in nanomaterials.

- Isobel Bennett: One of Australia's best-known marine biologists.

- Dorothy Hill: The first female Professor at an Australian university.

- Ruby Payne-Scott: An early leader in radio astronomy and radiophysics.

- Penny Sackett: An astronomer who became the first female Chief Scientist of Australia in 2008.

- Fiona Stanley: An epidemiologist known for her research on child and maternal health.

- Michelle Simmons: A quantum physicist known for her research on atomic-scale silicon quantum devices.

Israel After World War II

- Ada Yonath: The first woman from the Middle East to win a Nobel Prize in the sciences. She won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009 for her studies on the structure of the ribosome.

Latin America

Maria Nieves Garcia-Casal: The first female scientist and nutritionist from Latin America to lead the Latin America Society of Nutrition.

Angela Restrepo Moreno: A microbiologist from Colombia. She studies fungi and the diseases they cause, especially Paracoccidioidomycosis, a disease found only in Latin America. She co-founded a non-profit for scientific research.

Susana López Charretón: A virologist from Mexico who studies the rotavirus. Her work helped scientists learn how the virus enters cells and multiplies. She won the Carlos J. Finlay Prize for Microbiology in 2001 and the L'Oréal-UNESCO "Woman in Science" prize in 2012.

Liliana Quintanar Vera: A Mexican chemist. Her research focuses on how copper interacts with proteins in neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, and degenerative diseases like diabetes. She has won several awards, including the L'Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science Award.

Nobel Prize Winners

The Nobel Prize has been given to women 61 times between 1901 and 2022. Marie Sklodowska-Curie won twice (Physics in 1903 and Chemistry in 1911). This means 60 different women have won. 24 women have won in physics, chemistry, or physiology/medicine.

Chemistry

- 2022 – Carolyn Bertozzi

- 2020 – Emmanuelle Charpentier, Jennifer Doudna

- 2018 – Frances Arnold

- 2009 – Ada E. Yonath

- 1964 – Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

- 1935 – Irène Joliot-Curie

- 1911 – Marie Sklodowska-Curie

Physics

- 2020 – Andrea Ghez

- 2018 – Donna Strickland

- 1963 – Maria Goeppert-Mayer

- 1903 – Marie Sklodowska-Curie

Physiology or Medicine

- 2015 – Youyou Tu

- 2014 – May-Britt Moser

- 2009 – Elizabeth H. Blackburn

- 2009 – Carol W. Greider

- 2008 – Françoise Barré-Sinoussi

- 2004 – Linda B. Buck

- 1995 – Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard

- 1988 – Gertrude B. Elion

- 1986 – Rita Levi-Montalcini

- 1983 – Barbara McClintock

- 1977 – Rosalyn Yalow

- 1947 – Gerty Cori

Fields Medal Winners

The Fields Medal is a very important award in mathematics.

- 2014 – Maryam Mirzakhani: The first woman to win this prize. She was an Iranian mathematician and professor at Stanford University.

- 2022 – Maryna Viazovska

Women in Space

While women have made huge progress in STEM fields, they are still not as many as men in space flight. Out of 556 people who have traveled to space, only 65 were women. This means only about 11% of astronauts have been women.

In the 1960s, the American space program was starting. But women were not allowed to be astronauts because they had to be military pilots, a job women couldn't do then. Some officials also claimed it was hard to design space suits for women.

In the early 1960s, a doctor named William Randolph Lovelace II wanted to see if women could pass the same training as the male astronauts. He chose 13 female pilots, called the "Mercury 13", and put them through the same tests. The women actually performed better than the men! However, NASA still didn't allow women in space. Congressional hearings were held to investigate this discrimination. Jerrie Cobb, the first woman to pass Lovelace's tests, testified: "I find it a little ridiculous when I read in a newspaper that there is a place called Chimp College in New Mexico where they are training chimpanzees for space flight, one a female named Glenda. I think it would be at least as important to let the women undergo this training for space flight." But NASA officials, including astronauts John Glenn and Scott Carpenter, argued that women were not suited for space. So, NASA didn't send a woman to space until 1983.

Even though the US didn't allow women in space then, other countries did. Valentina Tereshkova, a cosmonaut from the Soviet Union, was the first woman to fly in space in 1963. She had no piloting experience but orbited Earth 48 times.

Sally Ride was the third woman in space and the first American woman. In 1978, she and five other women were accepted into the first astronaut class that allowed women. In 1983, Ride flew on the Challenger for the STS-7 mission.

NASA has become more inclusive. The number of women in NASA's astronaut classes has steadily grown. The most recent class was 45% women, and the one before was 50%. In 2019, the first all-female spacewalk happened at the International Space Station.

See also

- History of science

- International Day of Women and Girls in Science

- List of inventions and discoveries by women

- List of female scientists before the 20th century

- List of female scientists in the 20th century

- List of female scientists in the 21st century

- List of female mathematicians

- List of female Nobel laureates

- Matilda effect

- Organizations for women in science

- Prizes, medals, and awards for women in science

- Timeline of women in science

- Timeline of women in science in the United States

- Women in computing

- Women in engineering

- Women in medicine

- Women in physics

- Women in STEM fields

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |