Jennifer Doudna facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jennifer Doudna

|

|

|---|---|

Doudna in 2023

|

|

| Born |

Jennifer Anne Doudna

February 19, 1964 Washington, D.C., U.S.

|

| Education |

|

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Tom Griffin

(m. 1988, divorced)Jamie Cate

(m. 2000) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Towards the Design of an RNA Replicase (1989) |

| Doctoral advisor | Jack Szostak |

| Other academic advisors | Thomas Cech |

| Doctoral students |

|

Jennifer Doudna is an American biochemist. She is famous for her groundbreaking work in CRISPR gene editing. This technology allows scientists to make precise changes to DNA.

In 2020, she won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Emmanuelle Charpentier. They received the award for creating a way to edit genomes. A genome is the complete set of DNA in an organism.

Doudna is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley. She has also been a researcher with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute since 1997.

In 2012, Doudna and Charpentier suggested that CRISPR-Cas9 could be used to edit genomes. CRISPR-Cas9 are special tools found in bacteria. This discovery is considered one of the most important in the history of biology. Doudna has been a key leader in the "CRISPR revolution."

Doudna has received many awards. These include the 2000 Alan T. Waterman Award for her research on ribozymes. She also received the 2015 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences for the CRISPR-Cas9 technology. In 2015, Time magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people. In 2023, she joined the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Early Life and Education

Jennifer Doudna was born on February 19, 1964, in Washington, D.C. Her father had a PhD in English literature. Her mother had a master's degree in education.

When Jennifer was seven, her family moved to Hawaii. Her father taught American literature at the University of Hawaii at Hilo. Her mother also taught history at a local college.

Growing Up in Hawaii

Growing up in Hilo, Hawaii, Jennifer loved the local plants and animals. Her father enjoyed science books. When she was in sixth grade, he gave her The Double Helix by James Watson. This book, about the discovery of DNA's structure, greatly inspired her.

Doudna's interest in science grew in school. Her 10th-grade chemistry teacher, Jeanette Wong, was a big influence. A visiting speaker on cancer cells also encouraged her to pursue science. She worked in a lab at the University of Hawaii at Hilo during a summer. She graduated from Hilo High School in 1981.

College and Graduate Studies

Doudna attended Pomona College in California. She studied biochemistry. At first, she doubted her ability in science. But her French teacher encouraged her to stick with it. Chemistry professors Fred Grieman and Corwin Hansch also helped her. She earned her bachelor's degree in biochemistry in 1985.

She then went to Harvard Medical School for her PhD. She earned her degree in biological chemistry and molecular pharmacology in 1989. Her PhD research was about a system that made a self-copying RNA more efficient. Her advisor was Jack W. Szostak.

Career and Research

After her PhD, Doudna did research at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. From 1991 to 1994, she worked with Thomas Cech at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Studying RNA Enzymes

Early in her career, Doudna studied RNA enzymes, also called ribozymes. She wanted to understand their structure and how they work. While working with Jack Szostak, she changed a natural ribozyme. This new ribozyme could copy RNA.

Doudna realized she needed to see the ribozymes' shapes to understand them better. She joined Thomas Cech's lab to use X-ray crystallography. This method helps scientists see the 3D structure of tiny molecules. She started this work in 1991 and finished it at Yale University in 1996. Doudna became a professor at Yale in 1994.

Seeing Ribozyme Structures

At Yale, Doudna's team successfully used X-rays to see the 3D structure of a key part of a ribozyme. They found that five magnesium ions formed a core in the ribozyme. This core helped the molecule fold into its correct shape. This was similar to how proteins fold.

Her group also studied other ribozymes, like the Hepatitis Delta Virus ribozyme. This work helped scientists understand how large RNA molecules are shaped.

Moving to Berkeley

In 2002, Doudna moved to the University of California, Berkeley. She became a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology. At Berkeley, she could use the synchrotron at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. This machine provides powerful X-rays for her experiments.

In 2009, she briefly worked at Genentech. But she soon returned to Berkeley to focus on CRISPR research.

As of 2023, Doudna leads the Innovative Genomics Institute. This institute works to develop genome editing technology. They apply it to solve big problems in health, farming, and climate change. Her lab now studies how CRISPR-Cas systems work. They also create new ways to use CRISPR for gene editing.

The CRISPR-Cas9 Discovery

In 2006, Jillian Banfield introduced Doudna to CRISPR. In 2012, Doudna and her team made a major discovery. They found a way to edit DNA much faster and easier.

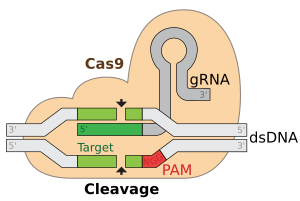

Their discovery uses a protein called Cas9. This protein comes from the "CRISPR" immune system of bacteria. Cas9 works like tiny scissors. It teams up with a guide RNA molecule. This team finds and cuts the DNA of viruses, stopping them from infecting the bacteria.

Yoshizumi Ishino first discovered this system in 1987. But Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier showed how to program Cas9. They showed that different RNA molecules could guide Cas9 to cut and edit different DNA sequences.

This discovery made it much simpler to edit DNA. Many research groups have since used it. It helps in studying cells, plants, and animals. It also shows promise for treating diseases like sickle cell anemia and cystic fibrosis.

Doudna and other scientists have discussed the ethics of gene editing. They called for a temporary stop on using CRISPR to make changes that could be passed down to future generations. Doudna supports using CRISPR to edit genes in body cells, which are not passed on.

CRISPR and Patents

The CRISPR system was a new way to edit DNA. This led to a race to get patents for the technique. Doudna and UC Berkeley applied for a patent. Another group at the Broad Institute also applied.

The Broad Institute group showed that CRISPR-Cas9 could edit human cells. A patent was granted to them first. UC Berkeley then filed a lawsuit. In 2017, the court sided with the Broad Institute. They argued that the Broad group had first shown the method worked in human cells. UC Berkeley appealed, saying they had clearly explained how to do this. In 2018, the appeals court again sided with the Broad Institute.

However, UC Berkeley also received a patent for the general CRISPR technique. In Europe, the Broad Institute's claim was rejected due to a technical issue.

Doudna helped start several companies to use CRISPR technology. These include Caribou Biosciences (2011), Editas Medicine (2013), Intellia Therapeutics, and Scribe Therapeutics.

In 2017, Doudna co-wrote a book called A Crack in Creation: Gene Editing and the Unthinkable Power to Control Evolution. This book explains the CRISPR breakthrough to the general public.

Doudna also discovered how the hepatitis C virus makes its proteins. This research could lead to new medicines.

Doudna has said, "I have so much optimism about what CRISPR can do to help cure unaddressed genetic diseases and improve sustainable agriculture. But I'm also concerned that the benefits of the technology might not reach those who need it most."

Mammoth Biosciences

In 2017, Doudna co-founded Mammoth Biosciences. This company focuses on making bio-sensing tests more available. These tests can help with healthcare, farming, and monitoring the environment. The company has raised significant funding.

Helping with COVID-19

Starting in March 2020, Doudna helped organize efforts to use CRISPR for the COVID-19 pandemic. Her team at the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) created a testing center. This center processed over 500,000 patient samples. Mammoth Biosciences also developed a fast, CRISPR-based COVID-19 test. This test is quicker and cheaper than other common tests.

Other Activities

Doudna is the founder and chair of the Innovative Genomics Institute. She is also a scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL). She is a senior researcher at the Gladstone Institutes. She is also a professor at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). In 2025, a new supercomputer at LBNL was named after Doudna.

Doudna is on the science advisory boards of several companies. These include Caribou, Intellia, Mammoth, and Scribe. She also advises Sixth Street Partners on investments related to CRISPR.

Personal Life

Jennifer Doudna married Tom Griffin in 1988. He was also a graduate student at Harvard. They later divorced.

As a researcher at the University of Colorado, Doudna met Jamie Cate. He was a graduate student. They worked together on a project to study the structure of a ribozyme. Doudna and Cate married in Hawaii in 2000.

Cate later became a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Doudna followed him to Harvard. But in 2002, they both accepted professor positions at Berkeley. They moved there together. Cate liked the less formal environment on the West Coast. Doudna liked that Berkeley is a public university.

Jamie Cate is now a professor at Berkeley. He works on changing yeast to make more biofuel. Doudna and Cate have a son, born in 2002. He attends UC Berkeley, studying electrical engineering and computer science. The family lives in Berkeley.

Awards and Honors

Doudna received the 1996 Beckman Young Investigators Award. In 2000, she won the Alan T. Waterman Award. This is the National Science Foundation's highest honor for young researchers. She received it for her work on ribozyme structure. In 2001, she received the Eli Lilly Award in Biological Chemistry.

In 2015, she and Emmanuelle Charpentier received the Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences. This was for their work on CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. In 2016, they also received the Canada Gairdner International Award. She also won the Heineken Prize for Biochemistry and Biophysics in 2016.

Other awards include the Gruber Prize in Genetics (2015), the Tang Prize (2016), the Japan Prize (2017), and the Albany Medical Center Prize (2017). In 2018, Doudna received the NAS Award in Chemical Sciences. She also won the Pearl Meister Greengard Prize and a Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society.

Also in 2018, she received the Kavli Prize in Nanoscience. In 2019, she received the Harvey Prize and the Lui Che Woo Prize. In 2020, she won the Wolf Prize in Medicine. And in 2020, Doudna and Charpentier were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. In 2025, she received the National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

She was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2002. She joined the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2003. In 2010, she became a member of the National Academy of Medicine. In 2014, she joined the National Academy of Inventors. In 2016, she became a Foreign Member of the Royal Society.

In 2015, Time magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people. In 2016, she was a runner-up for Time Person of the Year. In 2021, Pope Francis appointed Doudna as a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.

See also

In Spanish: Jennifer Doudna para niños

In Spanish: Jennifer Doudna para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |