Women in computing facts for kids

In the early 1900s, women were some of the very first computer programmers. They helped a lot in building the computer industry. Over time, as technology changed, the role of women in programming also changed. Sadly, their amazing achievements were often not fully recognized in history books.

Even before computers, women were busy with scientific calculations. For example, Nicole-Reine Lepaute helped predict when Halley's Comet would return. Maria Mitchell calculated how the planet Venus moved. The very first set of instructions (called an algorithm) for a computer was created by Ada Lovelace. She was a true pioneer! Later, Grace Hopper was the first person to create a compiler, which translates programming code into something a computer understands.

Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, especially during World War II, many programmers were women. Famous groups like the Harvard Computers, codebreakers at Bletchley Park, and engineers at NASA included many women.

After the 1960s, the "soft work" of programming, which women mostly did, grew into modern software. But the number of women in computing started to drop. People have studied why there are fewer women in computing since the late 1900s, but there's no single clear answer. Still, many women kept making huge contributions to the tech world. Efforts were also made to bring more women back into the industry. In the 2000s, women like Meg Whitman (from Hewlett Packard Enterprise) and Marissa Mayer (from Yahoo! and Google) held important leadership roles in big tech companies.

Contents

- History of Women in Computing

- The 1700s: Predicting Comets

- The 1800s: First Programmers and Star Gazers

- The 1910s: World War I Calculations

- The 1920s: New Machines and Electrical Engineers

- The 1930s: NASA's Early Computers

- The 1940s: War Efforts and ENIAC

- The 1950s: Compilers and GPS

- The 1960s: New Languages and Space Missions

- The 1970s: Early Internet and User Interfaces

- The 1980s: Icons, Games, and the Internet

- The 1990s: Hypertext and Online Communities

- The 2000s: Bridging the Gap

- The 2010s: Continued Progress

- Gender Gap in Computing

- Awards for Women in Computing

- Organizations Supporting Women in Computing

- Images for kids

- See also

History of Women in Computing

The 1700s: Predicting Comets

Nicole-Reine Etable de la Brière Lepaute was part of a team of "human computers." These were people who did complex math by hand. She worked with two men, Alexis-Claude Clairaut and Joseph-Jérôme Le Français de Lalande. Their big task was to predict when Halley's Comet would return. They started their calculations in 1757, working long hours. They broke down huge math problems into smaller parts, solved each part, and then put them all together. Lepaute continued doing calculations for the rest of her life. She even published predictions for solar eclipses.

The 1800s: First Programmers and Star Gazers

Maria Mitchell was one of the first "computers" for the American Nautical Almanac. Her job was to calculate the movement of the planet Venus. Even though the Almanac didn't happen, Mitchell became the first astronomy professor at Vassar College.

Ada Lovelace was the first person to write an algorithm for a modern computer. This was for the Analytical Engine designed by Charles Babbage. Because of this, she is often called the first computer programmer. Lovelace met Babbage when she was 17. She translated a paper about the Analytical Engine and added her own ideas. She imagined how the engine could handle inputs, outputs, processing, and data storage. She also created the first computer program to calculate Bernoulli numbers. Lovelace signed her work with her initials, AAL, to avoid sounding like she was bragging.

After the American Civil War, more women were hired as human computers in the United States. Many were war widows needing to support themselves. Others were hired because there weren't enough men for the jobs.

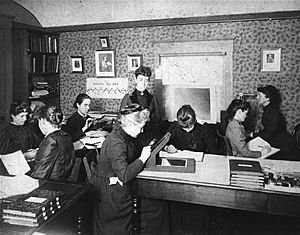

In 1875, Anna Winlock became a computer for the Harvard Observatory. By 1880, Edward Charles Pickering hired several women at Harvard University. He knew women could do the work well and for less pay. These women, known as the Harvard Computers, did detailed work that men found boring. They cataloged thousands of stars, found the Horsehead Nebula, and created a system to describe stars. One of them, Annie Jump Cannon, could classify three stars per minute! Even though their work was important, they were paid less than factory workers.

By the 1890s, many women computers were college graduates looking for useful jobs. Florence Tebb Weldon used calculations to support Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. Alice Lee also worked in biology. Karl Pearson hired two sisters, Beatrice and Frances Cave-Brown-Cave, to work as part-time computers in his Biometrics Lab.

The 1910s: World War I Calculations

During World War I, Karl Pearson's lab helped the British Ministry of Munitions with ballistics calculations. Beatrice Cave-Browne-Cave calculated paths for bomb shells. In the United States, women were hired in 1918 to calculate ballistics. Elizabeth Webb Wilson was a chief computer. After the war, many women who worked as ballistics computers struggled to find similar jobs. Wilson ended up teaching high school math.

The 1920s: New Machines and Electrical Engineers

In the early 1920s, professor George W. Snedecor at Iowa State University used new punch-card machines and calculators. He also worked with human computers, mostly women, like Mary Clem. Clem created the term "zero check" to find errors in calculations. Her computing lab became very powerful.

Women computers also worked at the American Telephone and Telegraph company. They helped electrical engineers figure out how to boost phone signals. Clara Froelich studied IBM tabulating equipment to adapt machine methods for calculations.

Edith Clarke was the first woman to get a degree in electrical engineering. She was also the first professionally employed electrical engineer in the U.S. She was hired by General Electric in 1923. Clarke also patented a graphical calculator in 1921 to solve power line problems.

The 1930s: NASA's Early Computers

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which later became NASA, hired five women in 1935. They formed a "computer pool" and worked on data from wind tunnel and flight tests.

The 1940s: War Efforts and ENIAC

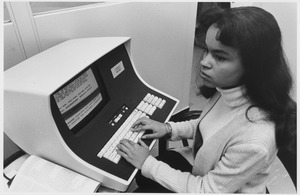

Through the 1940s, "tedious" computing was often seen as "women's work." A term called "kilogirl" was even invented, meaning about a thousand hours of computing work. While media praised women's war efforts, their complex computer work was often downplayed. During WWII, women did most of the ballistics computing. By 1943, almost all computers were women. One report said "programming requires lots of patience, persistence and a capacity for detail and those are traits that many girls have."

NACA expanded its women computer pool. In 1942, engineers admitted that "the girl computers do the work more rapidly and accurately than they could." In 1943, two groups, separated by race, worked at Langley Air Force Base. The Black women were the West Area Computers. Unlike white women, they often had to re-do college courses and rarely got promotions.

Women also worked on ballistic missile calculations. In 1948, women like Barbara Paulson calculated missile paths for the WAC Corporal.

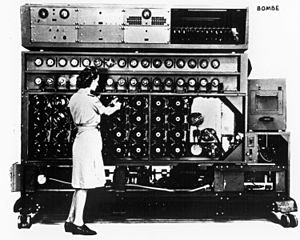

Women were also involved in cryptography (code-breaking). After some initial resistance, many operated Bombe machines. Joyce Aylard operated the Bombe to break the Enigma code. Joan Clarke was a cryptographer who worked with Alan Turing at Bletchley Park. When she was promoted, she was listed as a linguist because there was no "senior female cryptanalyst" position. Her decryption technique, unlike men's, was not named after her. Other cryptographers included Margaret Rock and Mavis Lever. In the U.S., women from the WAVES operated American Bombe machines.

Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil invented a frequency hopping method to control torpedoes remotely. The Navy didn't use it then, but they got a patent in 1942. This technique is now used in Bluetooth and Wi-Fi!

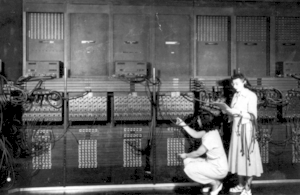

In 1944, six female mathematicians programmed the ENIAC computer. They were Marlyn Meltzer, Betty Holberton, Kathleen Antonelli, Ruth Teitelbaum, Jean Bartik, and Frances Spence. They were called the "ENIAC girls." Adele Goldstine was their teacher. They were told they wouldn't get professional promotions, which were only for men. Designing hardware was "men's work," and programming software was "women's work." But these women understood and worked with the ENIAC's hardware too. When ENIAC was shown to the public in 1946, the women prepared the machine and its programs. But their work was not mentioned in official reports, and they weren't invited to the celebration dinner.

In Canada, Beatrice Worsley started at the National Research Council in 1947. She built a differential analyzer in 1948. She also worked with IBM machines for Atomic Energy of Canada Limited. She went to the University of Cambridge in 1949 and wrote the first program run on the EDSAC on May 6, 1949.

Grace Hopper was one of the first programmers for the Harvard Mark I computer. She started in 1943, programming the Mark I and writing a 500-page manual for it. Even though her manual was widely used, she wasn't specifically credited. Hopper is often linked to the terms "bug" and "debugging" after a moth caused the Mark II to malfunction. While a moth was found, these terms were already used by programmers.

The 1950s: Compilers and GPS

Grace Hopper continued her work in the 1950s. She brought the idea of compilers to UNIVAC, which she joined in 1949. Other women hired to program UNIVAC included Adele Mildred Koss, Frances E. Holberton, Jean Bartik, Frances Morello, and Lillian Jay. Hopper and her team developed the FLOW-MATIC programming language for UNIVAC. Holberton wrote a code, C-10, for keyboard inputs. She also created the Sort Merge Generator in 1951, which was the first time a computer "used a program to write a program." Holberton even suggested that computers should be beige, a trend that lasted for years!

Klara Dan von Neumann was a main programmer for the MANIAC I, an advanced ENIAC version. Her work helped improve weather prediction.

NACA (later NASA) kept hiring women computers after WWII. By the 1950s, a team at the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, included Annie Easley, Katherine Johnson, and Kathryn Peddrew. At the National Bureau of Standards, Margaret R. Fox joined the Electronic Computer Laboratory in 1951. In 1956, Gladys West was hired by the U.S. Naval Weapons Laboratory. West's calculations helped develop GPS.

At Convair Aircraft Corporation, Joyce Currie Little was a programmer analyzing wind tunnel data. She used punch cards on an IBM 650. To save time delivering the cards between buildings, she and a colleague used roller skates!

In Israel, Thelma Estrin worked on designing WEIZAC, one of the world's first large electronic computers. In the Soviet Union, a team of women helped build the first digital computer in 1951. In the UK, Kathleen Booth worked with her husband, Andrew Booth, on several computers. Kathleen was the programmer, and Andrew built the machines. Kathleen developed Assembly language at this time.

Mary Coombs (England) became the first female commercial programmer in 1952, working on the LEO computers.

Kateryna Yushchenko (Ukraine) created the Address programming language in 1955. She also invented "indirect addressing of the highest rank," which is like inventing Pointers in computer programming.

The 1960s: New Languages and Space Missions

Milly Koss, who worked with Hopper at UNIVAC, joined Control Data Corporation (CDC) in 1965. She developed algorithms for computer graphics.

Mary K. Hawes of Burroughs Corporation helped start a meeting in 1959 to create a shared computer language for businesses. Six people, including Hopper, discussed this idea. Hopper became involved in developing COBOL (Common Business Oriented Language). She made new, easier ways to write computer code. Betty Holberton also edited COBOL before it was published. IBM was slow to use COBOL, but it became a standard in 1962. Many compilers and generators for COBOL were created or improved by women like Koss and Jean E. Sammet.

Sammet, who worked at IBM from 1961, developed the programming language FORMAC. Her 1969 book, Programming Languages: History and Fundamentals, was considered the "standard work on programming languages."

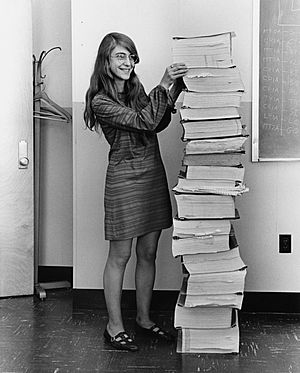

Between 1961 and 1963, Margaret Hamilton studied software reliability for the US SAGE air defense system. In 1965, she was in charge of programming the flight software for the Apollo mission computers. After Hamilton finished the code, it was sent to Raytheon. There, "expert seamstresses" called the "Little Old Ladies" actually hardwired the code by threading copper wire through magnetic rings. Each system could store over 12,000 words.

In 1964, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced a "White-Hot" technology revolution. Since women held most computing jobs then, it was hoped this would improve their careers. In 1965, Sister Mary Kenneth Keller became the first American woman to earn a doctorate in computer science. Keller helped develop BASIC while at Dartmouth College, which "broke the 'men only' rule" for her to use its computer science center.

In 1966, Frances "Fran" Elizabeth Allen at IBM Research published a paper on "Program Optimization." This paper introduced using graph structures to analyze and improve computer programs.

Christine Darden joined NASA's computing pool in 1967. Women were also involved in developing Whirlwind I, like Judy Clapp. She created a prototype air defense system that used radar to track planes.

In 1969, Elizabeth "Jake" Feinler at Stanford University created the first Resource Handbook for ARPANET. This led to the ARPANET directory, built by Feinler and mostly women. Without it, navigating ARPANET was "nearly impossible."

By the end of the 1960s, the number of women programmers started to decrease. While women were 30-50% of programmers, few were promoted, and they were paid much less than men. Even though magazines like Cosmopolitan saw a bright future for women in computers, they were still being pushed to the side.

The 1970s: Early Internet and User Interfaces

In the early 1970s, Pam Hardt-English led a group to create an early computer network called Resource One. Her idea to connect Bay Area bookstores, libraries, and Project One was like an early version of the Internet. They got an expensive SDS-940 computer and created an electronic library. This became the Community Memory database, maintained by hacker Jude Milhon.

Elizabeth "Jake" Feinler and her team created the first WHOIS directory. Feinler set up a server at the Network Information Center (NIC) at Stanford. This directory could find information about people or organizations. She also worked on creating domains, suggesting categories like .mil for military and .edu for educational institutions. Feinler worked for NIC until 1989.

Jean E. Sammet was the first woman president of the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) from 1974 to 1976.

Adele Goldberg was one of seven programmers who developed Smalltalk in the 1970s. She wrote most of its documentation. Smalltalk was one of the first object-oriented programming languages. It was also a base for the modern graphic user interface (GUI), which you see on your computer or phone today. Smalltalk influenced Apple's Apple Lisa (1983) and Macintosh (1984), and later Windows 1.0 (1985).

In the late 1970s, women like Paulson and Sue Finley wrote programs for the Voyager mission. These codes are still in Voyager's memory as it travels out of our Solar System. In 1979, Ruzena Bajcsy founded the GRASP Lab at the University of Pennsylvania for robotics and AI.

Joan Margaret Winters worked at IBM on a "human factors project" called SHARE. This group researched how software should be designed to be easy for people to use.

Erna Schneider Hoover developed a computer system for telephone calls. Her software patent, issued in 1971, was one of the very first software patents ever granted.

The 1980s: Icons, Games, and the Internet

Gwen Bell started the Computer Museum in 1980, collecting computer artifacts. Adele Goldberg served as ACM president again from 1984 to 1986. In 1986, Lixia Zhang was the only woman and graduate student at early Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) meetings. Zhang was important in early Internet development. In 1982, Marsha R. Williams became the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in computer science.

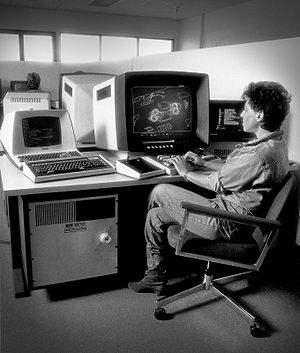

Susan Kare worked with Steve Jobs to design the original icons for the Macintosh. She created the moving watch, paintbrush, and trash can that made the Mac easy to use. She later designed icons for Windows 3.0. Nadia Magnenat Thalmann in Canada worked on computer animation to create "realistic virtual actors."

In human–computer interaction (HCI), French computer scientist Joëlle Coutaz developed the PAC model in 1987. Her group worked on user interface problems.

As Ethernet became standard for local computer networks, Radia Perlman at Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) was asked to fix its limits for large networks. In 1985, Perlman created a way to route information packets that allowed large networks like the Internet to work. Her solution, the Spanning Tree Protocol, took only a few days to design. In 1988, Stacy Horn created her own online community in New York called ECHO. She built it using UNIX and provided email accounts and chat forums. About half of ECHO's users were women.

Borka Jerman Blažič helped establish the Yugoslav Research and Academic Network (YUNAC) in 1989 and registered the .yu domain for her country.

Computer and video games became popular in the 1980s. Many were action-focused and not designed for girls. Dona Bailey designed Centipede as a reaction, saying "It didn't seem bad to shoot a bug." Carol Shaw, considered the first modern female game designer, released a 3D tic-tac-toe game for the Atari 2600 in 1980. Roberta Williams and her husband founded Sierra Online and pioneered graphic adventure games like Mystery House and King's Quest. These games had friendly graphics, humor, and puzzles. Brenda Laurel worked on porting arcade games to Atari computers and later wrote the manual for Maniac Mansion.

In 1984, the "Women Into Science and Engineering (WISE)" initiative started. A report found that few mothers and daughters used computers at home compared to fathers and sons. To change this, a company launched software for women. Anita Borg noticed few women in computer science and founded Systers, an email support group, in 1987.

The 1990s: Hypertext and Online Communities

By the 1990s, men mostly dominated computing. The number of female computer science graduates peaked in 1984 at 37% and then dropped. Despite this, women were very involved in hypertext and hypermedia projects. A team of women at Brown University, including Nicole Yankelovich and Karen Catlin, developed Intermedia and invented the anchor link. Janet Walker created the first system to use bookmarks. In 1989, Wendy Hall created Microcosm, a hypertext project based on multimedia. Cathy Marshall worked on the NoteCards system at Xerox PARC, which influenced Apple's HyperCard. As the Internet grew into the World Wide Web, developers like Hall adapted their programs. In 1994, Hall helped organize the first Web conference.

Sarah Allen, co-founder of After Effects, co-founded a software company called CoSA in 1990. In 1995, she became the lead developer for the Shockwave team at Macromedia, working on Shockwave Mulituser Server, Flash Media Server, and Flash video.

With the Internet's popularity in the 1990s, online spaces for women appeared. These included Women's WIRE and LinuxChix. Women's WIRE, launched in 1993, was the first Internet company to target women. The Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing conference was first held in 1994 by Anita Borg.

Game designer Brenda Laurel started at Interval Research in 1992. She studied how girls and boys played video games. After interviewing many children and adults, she found that games weren't designed with girls' interests in mind. Girls wanted more open worlds and characters they could interact with. Her research led to her team getting their own company, Purple Moon, in 1996. Also in 1996, Mattel's Barbie Fashion Designer became the first best-selling game for girls. Purple Moon's games also sold well.

Jaime Levy created one of the first e-Zines (electronic magazines) in the early 1990s, starting with CyberRag. It had articles, games, and animations on diskettes for Macs. She later worked as creative director for Word online magazine.

In China, Hu Qiheng led the team that installed China's first TCP/IP connection to the Internet on April 20, 1994. In 1995, Rosemary Candlin wrote software for CERN in Geneva. In the early 1990s, Nancy Hafkin helped enable email connections in 10 African countries. From 1999, Anne-Marie Eklund Löwinder worked with Domain Name System Security Extensions (DNSSEC) in Sweden. She made sure the .se domain was the world's first top-level domain signed with DNSSEC.

In the late 1990s, research by Jane Margolis led Carnegie Mellon University to try to fix the male-female imbalance in computer science.

From the late 1980s to mid-1990s, Misha Mahowald developed key ideas in Neuromorphic engineering, which studies how brains compute. An award, the Misha Mahowald Prize, is named after her.

The 2000s: Bridging the Gap

In the 2000s, many efforts were made to get more women involved in computing again. A 2001 survey found that while both sexes used computers and the Internet equally, women were five times less likely to choose it as a career. Journalist Emily Chang noted that job interviews often looked for introverted programmers, which fit the stereotype of an unsocial white male nerd.

In 2004, the National Center for Women & Information Technology was started by Lucy Sanders to help close the gender gap. Carnegie Mellon University tried to increase diversity in computer science. They selected students based on leadership, community involvement, and strong math/science skills, not just traditional programming experience. This brought in more women and also led to better quality students overall.

The 2010s: Continued Progress

Even with some pioneering designers, video games are still often seen as more for men. A 2013 survey found only 22% of game designers were women, though this was higher than before. To make open-source projects more welcoming, Coraline Ada Ehmke created the Contributor Covenant in 2014. By 2018, over 40,000 software projects, including TensorFlow and Linux, used it. In 2014, Danielle George, a professor at the School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, University of Manchester, gave the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures. She showed simple experiments with computer hardware and even demonstrated a giant game of Tetris by controlling lights in an office building.

In 2017, Michelle Simmons founded Australia's first quantum computing company. Her team is making great progress in developing a 10-qubit silicon quantum integrated circuit. In the same year, Doina Precup became the head of DeepMind Montreal, working on artificial intelligence.

Gender Gap in Computing

Computing started with many women, but this changed in Western countries after World War II. In the US, companies wanted to hire an "ideal programmer." Psychologists created a test, and out of 1400 people, 1200 chosen were men. This test was very influential and focused on introverted men. In Britain, women programmers were often laid off after the war, causing the country to lose its lead in computer science.

There are many ideas about why there are fewer women in computer science, often ignoring history and social reasons. In 1992, John Gray's book Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus suggested men and women think differently, leading to different approaches to technology. A big problem is that women find the work environment unpleasant, so they leave. Also, if there are few women in a computer science class, those few can feel alone and not belong, which might make them leave the field.

The gender gap in IT is not the same everywhere. In India, there are many more women computer scientists than in the West. In 2015, over half of Internet business owners in China were women. Bulgaria and Romania in Europe have high rates of women in computer programming. In Saudi Arabia, 59% of computer science students in government universities were Arab women in 2014. Some suggest the gap is bigger in countries where men and women are treated more equally, which goes against ideas that society is generally to blame. However, the number of African American female computer scientists in the US is much lower than the global average. In tech companies, the ratio of men to women can change by job. For example, while most software developers might be male, many usability designers and project managers are female.

In 1991, Massachusetts Institute of Technology student Ellen Spertus wrote an essay, "Why Are There So Few Women in Computer Science?" It looked at sexism in IT. She later taught computer science at Mills College to get more women interested. A key problem is a lack of female role models in IT. Also, computer programmers in movies and media are usually male.

Wendy Hall from the University of Southampton said computers became less appealing to women in the 1980s when they were "sold as toys for boys." She believes this cultural idea has stuck around. Kathleen Lehman from UCLA said women often aim for perfection and get discouraged when code doesn't work, while men might see it as a learning experience. A report in The Daily Telegraph suggested women generally prefer jobs that involve working with people, while men prefer jobs focused on objects and tasks. One issue is that computer history often focuses on hardware, which was male-dominated, even though women wrote most of the software early on.

In 2013, a National Public Radio report said 20% of computer programmers in the US are female. There's no single agreement on why there are fewer women in computing. In 2017, an engineer was fired from Google for saying there was a biological reason for fewer female computer scientists.

Dame Stephanie Shirley, using the name Steve Shirley, helped women in computing in the UK. She started a software company, Freelance Programmers, which allowed women to work from home and part-time.

Awards for Women in Computing

The Association for Computing Machinery Turing Award is sometimes called the "Nobel Prize" of computing. Between 1966 and 2015, three women have won this award:

- 2006 – Frances "Fran" Elizabeth Allen

- 2008 – Barbara Liskov

- 2012 – Shafi Goldwasser

The British Computer Society Information Retrieval Specialist Group (BCS IRSG) created an award in 2008 to honor Karen Spärck Jones. She was a remarkable woman in computer science. Four women have won the KSJ award between 2009 and 2017:

- 2009 – Mirella Lapata

- 2012 – Diane Kelly

- 2015 – Emine Yilmaz

- 2016 – Jaime Teevan

Organizations Supporting Women in Computing

Many important groups have been created to encourage women in the tech industry. The Association for Women in Computing was one of the first. It works to help women advance in computing jobs. The CRA-W: Committee on the Status of Women in Computing Research, started in 1991, focuses on increasing the number of women in Computer Science and Engineering (CSE) research and education. AnitaB.org hosts the yearly Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing conference. The National Center for Women & Information Technology is a non-profit that aims to increase the number of women in technology. Women in Technology International (WITI) is a global group dedicated to helping women in business and technology. The Arab Women in Computing has chapters worldwide and encourages women in technology, providing networking opportunities.

Some major societies have special groups for women. The Association for Computing Machinery's Council on Women in Computing (ACM-W) has over 36,000 members. BCSWomen is a women-only group of the British Computer Society, founded in 2001. In Ireland, the charity Teen Turn offers after-school training and work placements for girls. Women in Technology and Science (WITS) supports women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) fields.

The Women's Technology Empowerment Centre (W.TEC) is a non-profit that teaches technology to Nigerian women and girls. Black Girls Code is a non-profit that provides technology education to young African-American women.

Other groups for women in IT include Girl Develop It, which offers affordable programs for adult women to learn web and software development. Girl Geek Dinners is an international group for women of all ages. Girls Who Code is a national non-profit dedicated to closing the gender gap in technology. LinuxChix is a women-focused community in the open source movement. Systers is a moderated email list for mentoring women in the IT industry.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Mujeres en informática para niños

In Spanish: Mujeres en informática para niños

- African-American women in computer science

- Hidden Figures

- List of female mathematicians

- List of female scientists

- List of organizations for women in science

- List of prizes, medals, and awards for women in science

- List of women in the video game industry

- Timeline of women in computing

- Women and video games

- Women in computing in Canada

- Women in engineering

- Women in science

- Women in venture capital

- Women in the workforce

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |