Smalltalk facts for kids

|

|

| Paradigm | Object-oriented |

|---|---|

| Designed by | Adele Goldberg, Dan Ingalls, Alan Kay |

| Developer | Peter Deutsch, Adele Goldberg, Dan Ingalls, Ted Kaehler, Alan Kay, Diana Merry, Scott Wallace and Xerox PARC |

| First appeared | 1972 (development begun 1969) |

| Stable release |

Smalltalk-80 version 2 / 1980

|

| Typing discipline | objects, but in some implementations, strong or dynamic |

| Scope | Lexical (static) |

| Implementation language | Smalltalk |

| Platform | Xerox Alto (74181) |

| OS | Cross-platform (multi-platform) |

| Major implementations | |

| Amber, Dolphin Smalltalk, GemStone/S, GNU Smalltalk, Pharo, Smalltalk/X, Squeak, Cuis Smalltalk, VA Smalltalk, VisualWorks | |

| Influenced by | |

| Lisp, Simula, Euler, IMP, Planner, Logo, Sketchpad, ARPAnet, Burroughs B5000 | |

| Influenced | |

| AppleScript, Common Lisp Object System, Dart, Dylan, Erlang, Etoys, Go, Groovy, Io, Ioke, Java, Lasso, Logtalk, Newspeak, NewtonScript, Object REXX, Objective-C, PHP 5, Python, Raku, Ruby, Scala, Scratch, Self, Swift | |

|

|

|

Smalltalk is a special kind of programming language that uses "objects" to build programs. It was first created in the 1970s at Xerox PARC by smart scientists like Alan Kay and Adele Goldberg. They designed it to help people learn, especially in a way that encourages building and exploring.

In Smalltalk, programs are made of many small pieces called objects. These objects are like tiny workers that know how to do things and talk to each other by sending "messages." Imagine them as LEGO bricks that can move and communicate! Smalltalk was one of the first languages to use this "object-oriented" idea.

Even though it started for learning, Smalltalk became useful in business too. It is still used today. When it first came out, Smalltalk-80 introduced many new ideas for how to build programs using objects. Smalltalk also lets you change your program while it is running, which is very helpful for fixing things quickly.

Smalltalk-like languages are still being developed and have many users. In 1998, a standard version called ANSI Smalltalk was approved. In 2017, Smalltalk was even voted the second "most loved programming language" in a big survey!

Contents

- The Story of Smalltalk

- How Smalltalk Changed Computing

- How Objects Work

- Smalltalk Code Basics

- Building Classes and Methods

- Tools for Programmers

- Hello World Example

- Saving Your Work (Image-based Persistence)

- Changing Everything (Level of Access)

- Fast Code (Just-in-time Compilation)

- Different Smalltalk Versions

- Related Languages

- See also

The Story of Smalltalk

There are many different versions of Smalltalk. When people say "Smalltalk," they often mean Smalltalk-80, which was the first version made public in 1980. The first computers that ran Smalltalk were called Xerox Alto computers.

Smalltalk was created by Alan Kay and his team at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). Alan Kay designed most of the early versions. Adele Goldberg wrote most of the instructions, and Dan Ingalls built many of the first versions. The very first version, Smalltalk-71, was made by Kay in just a few mornings. He wanted to prove that a language based on "message passing" (like objects talking to each other) could be written in "a page of code."

Smalltalk-76 was a big update that made the system faster. It also had many tools that programmers still use today, like a way to look at and edit code. Smalltalk-80 added "metaclasses," which helped make sure that "everything is an object" in the language. This means even numbers and true/false values are treated as objects.

Smalltalk-80 was the first version shared outside of PARC in 1981. Companies like Apple and Hewlett-Packard got to try it out. A magazine called Byte even dedicated a whole issue to Smalltalk-80 in August 1981, which helped many people learn about it. This helped Smalltalk spread widely.

Today, two popular versions of Smalltalk are Squeak and VisualWorks. Squeak is an open-source version that came from the first Smalltalk-80. VisualWorks came from a later version, Smalltalk-80 version 2.

Over the years, different companies sold Smalltalk tools. IBM even had its own version called VisualAge/Smalltalk. However, in the late 1990s, many companies started focusing on Java instead. Still, companies like Cincom and Instantiations continue to sell Smalltalk tools.

The open-source Squeak version has a very active community. It was used to create the Etoys environment for the One Laptop per Child project, which helps kids learn to program. Pharo Smalltalk is another version of Squeak, used for research and in businesses. Since 2016, many Smalltalk environments use web tools like Seaside to build complex web applications more easily.

How Smalltalk Changed Computing

Smalltalk was one of the first object-oriented programming languages, inspired by an older language called Simula. Smalltalk has had a huge impact on many other programming languages that came after it, like Java, Python, and Ruby.

Smalltalk was also very popular for new ways of developing software quickly, like agile software development and rapid application development (RAD). Its powerful tools made it great for building and testing programs fast.

Smalltalk came from a bigger research project that helped create many things we use in computing today. Besides Smalltalk, this research led to early versions of hypertext (like links on the internet), graphical user interfaces (GUIs, like what you see on your computer screen), multimedia, the computer mouse, and the Internet. Alan Kay, one of Smalltalk's creators, even imagined a tablet computer called the Dynabook, which was a lot like modern tablets!

Smalltalk environments were often the first to develop common ways to design software, called "design patterns." One famous pattern is the model–view–controller (MVC) pattern, used for designing user interfaces. This pattern helps programmers show the same information in different ways.

Smalltalk also influenced the look and feel of computer interfaces, like the graphical user interface (GUI) and "what you see is what you get" (WYSIWYG) editors. The powerful tools for finding errors (debugging) and looking at objects that came with Smalltalk set the standard for many other programming tools.

How Objects Work

In Smalltalk, the main idea is the object. An object is always a specific example of a class. Classes are like blueprints or recipes that describe what an object is like and what it can do. For example, a window class might say that windows have a title and a size. It might also say that windows can be opened or closed. Each actual window object would have its own title and size, and each could be opened or closed.

A Smalltalk object can do three main things:

- It can hold information (references to other objects).

- It can receive a message from itself or another object.

- While doing something with a message, it can send messages to itself or other objects.

The information an object holds is private to that object. Other objects can only ask or change that information by sending messages. Any message can be sent to any object. If an object does not understand a message, the system will tell you there is an error. Alan Kay said that even though objects are important, "messaging" (objects talking to each other) is the most important idea in Smalltalk.

Unlike most other languages, you can change Smalltalk code while the program is running. This "live coding" is a big reason why Smalltalk programmers can be very productive.

Smalltalk is a "pure" object-oriented language. This means that everything, even numbers and true/false values, are objects. Operations on them are done by sending messages. For example, if you want to add 3 and 4, you send the message "+" to the object 3 with 4 as an argument. This makes the system very flexible. You can even change how basic things like numbers work! This is why people say, "In Smalltalk everything is an object."

Since classes are also objects, they can be asked questions like "what methods do you have?" or "what information do you store?". This makes it easy to look at, copy, and save objects. Smalltalk also lets you see what the program is doing as it runs. This helps with debugging and understanding how the program works.

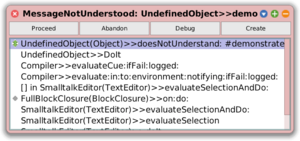

When an object receives a message it does not understand, the system sends it a special `doesNotUnderstand:` message. In an interactive Smalltalk system, this usually opens an error window. From this window, you can look at what happened, fix the code, and continue running the program!

Smalltalk Code Basics

Smalltalk-80 has a very simple set of rules for writing code. There are only five special "keywords" that have a fixed meaning: `true`, `false`, `nil` (nothing), `self` (the object itself), and `super` (the object's parent). These are like special words you cannot change. The main parts of the language are sending messages, giving values to variables, returning values, and writing down specific objects like numbers or blocks of code.

The saying "Smalltalk syntax fits on a postcard" means it is very simple. Here is a small example showing the basic parts:

exampleWithNumber: x

| y |

true & false not & (nil isNil) ifFalse: [self halt].

y := self size + super size.

#($a #a 'a' 1 1.0)

do: [ :each |

Transcript show: (each class name);

show: ' '].

^x < yWriting Down Values (Literals)

Here are some common ways to write values directly in Smalltalk:

- Numbers:

42

-42

123.45

1.2345e2 "This means 1.2345 times 10 to the power of 2"

2r10010010 "This is a binary number (base 2)"

16rA000 "This is a hexadecimal number (base 16)"You can even use other bases, like `36rSMALLTALK`.

- Characters: You put a dollar sign before them.

$A- Strings: These are sequences of characters inside single quotes.

'Hello, world!'To include a single quote inside a string, you use two single quotes:

'I said ''Hello, world!'' to them.'Double quotes do not need special handling:

'I said "Hello, world!" to them.'- Symbols: These are like strings but are guaranteed to be unique. They are fast to compare.

#'foo'If there are no spaces or special characters, you can write it shorter:

#foo- Arrays: These are lists of values inside parentheses.

#(1 2 3 4)This creates an array with four numbers.

- Code Blocks: These are like mini-programs or anonymous functions. They are written with square brackets.

[ :params | <message-expressions> ]For example, a block that takes a number `x` and adds 1 to it:

[:x | x + 1]You can run this block by sending it the `value:` message:

[:x | x + 1] value: 3This would give you 4.

Storing Information (Variables)

Variables are like containers for storing values. In Smalltalk, you declare temporary variables (used inside a method) by putting their names between vertical bars:

| index |This creates a variable named `index`, which starts with the value `nil` (nothing). You can declare many variables at once:

| index vowels |Giving Values (Assignment)

You give a value to a variable using the `:=` symbol:

vowels := 'aeiou'This puts the string `'aeiou'` into the `vowels` variable.

Talking to Objects (Messages)

Sending a message is the most basic way to make things happen in Smalltalk. Smalltalk uses a "single dispatch" system, meaning the object receiving the message decides what to do. There are three types of messages:

- Unary Messages: These have only a receiver object and no arguments.

42 factorialHere, `42` is the receiver, and `factorial` is the message. The result (the factorial of 42) can be stored in a variable:

aRatherBigNumber := 42 factorial- Keyword Messages: These messages carry extra objects as "arguments." Each argument has a keyword before it.

2 raisedTo: 4Here, `2` is the receiver, `4` is the argument, and `raisedTo:` is the message. The answer is 16. Keyword messages can have multiple arguments, making the code easier to read:

'hello world' indexOf: $o startingAt: 6The message here is `indexOf:startingAt:`. This finds the character 'o' in the string, starting from position 6. Instead of `new Rectangle(100, 200)` (which is hard to understand), Smalltalk uses:

Rectangle width: 100 height: 200This clearly shows that 100 is the width and 200 is the height.

- Binary Messages: These use special characters, often for math or logic.

3 + 4This sends the message `+` to the object `3` with `4` as an argument. The answer is 7.

3 > 4This sends the message `>` to `3` with `4` as an argument. The answer is `false`. Programmers can define new binary messages.

Combining Actions (Expressions)

Smalltalk is an "expression-based" language, meaning every action has a value. You can combine many message sends in one expression. Smalltalk follows a simple order: unary messages first, then binary, then keyword messages. Everything is evaluated from left to right. For example:

3 factorial + 4 factorial between: 10 and: 100This is calculated step-by-step: 1. `3 factorial` becomes `6`. 2. `4 factorial` becomes `24`. 3. `6 + 24` becomes `30`. 4. `30 between: 10 and: 100` becomes `true`.

You can use parentheses `()` to change the order of operations, just like in math.

3 + 4 * 5In Smalltalk, this is `(3 + 4) * 5`, which is `35`. To get `23`, you need `3 + (4 * 5)`.

You can also send a series of messages to the same object using semicolons `;`. This is called a "cascade":

Window new

label: 'Hello';

openThis creates a new window, sets its label to 'Hello', and then opens it, all in one go.

How Code Blocks Work

Code blocks (anonymous functions) are very important in Smalltalk. They let you write small pieces of code that can be passed around and run later. They are written with square brackets `[]`.

[ :params | <message-expressions> ]For example, this block takes a character and checks if it is a vowel:

[:aCharacter | aCharacter isVowel]Blocks are used for things like loops and conditional statements. For example, to select all positive numbers from a list:

positiveAmounts := allAmounts select: [:anAmount | anAmount isPositive]This sends the `select:` message to `allAmounts` with the block as an argument. The block is run for each amount, and if it returns `true`, the amount is included in `positiveAmounts`.

Building Classes and Methods

Smalltalk lets you define your own classes and methods. This is how you create your own types of objects and teach them what to do.

Defining Classes

Here is how you define a new class called `MessagePublisher` that is a type of `Object`:

Object subclass: #MessagePublisher

instanceVariableNames: ''

classVariableNames: ''

poolDictionaries: ''

category: 'Smalltalk Examples'This is actually a message sent to the `Object` class to create a new subclass. This shows that classes themselves are objects in Smalltalk!

Writing Methods

When an object receives a message, a method with the same name is run. Here is a simple method called `publish`:

publish

Transcript show: 'Hello World!'This method says that when a `MessagePublisher` object receives the `publish` message, it should show 'Hello World!' in the Transcript window.

Here is a method that takes two arguments and returns a value:

quadMultiply: i1 and: i2

"This method multiplies the given numbers by each other and the result by 4."

| mul |

mul := i1 * i2.

^mul * 4The method's name is `quadMultiply:and:`. The `^` symbol means "return this value."

Creating Objects (Instantiating Classes)

To create a new object from a class, you send the `new` message to the class:

MessagePublisher newThis creates a new `MessagePublisher` object. You can store it in a variable:

publisher := MessagePublisher newOr you can send a message to the new object right away:

MessagePublisher new publishTools for Programmers

Smalltalk was one of the first systems to have an Integrated Development Environment (IDE). This means it came with many tools to help you write code, draw graphics, and even make music. Smalltalk was also the first system to use the modern desktop idea of Windows, Icons, Menus, and Pointers (WIMP). Even though pointers were invented before, Smalltalk was the first to have overlapping windows and pop-up menus.

Here are five important tools in Smalltalk:

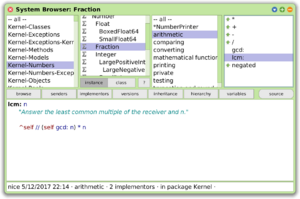

Browser

The Browser is the main tool for looking at and writing code. It helps you organize classes and methods into categories. It usually has five sections:

- System categories (like `Kernel-Numbers`)

- Classes in that category

- Message categories within a class

- Methods in that category

- The actual code for the selected method

You can use the browser to search for classes, find where a message is sent, or see all the places a message is used. It is great for both reading and writing code.

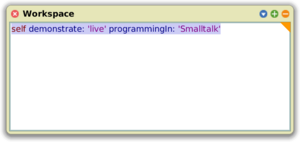

Workspace

A Workspace is a simple text editor where you can type Smalltalk code and run it. You can select code and choose "do it" to run it, "print it" to run it and see the result, or "inspect it" to open an Inspector on the result. The code area in the Browser is also a workspace, so you can test code while you are writing methods.

Transcript

The Transcript is a special window where programs can show text output. If you send `Transcript show: 'Hello, world!'`, the text 'Hello, world!' will appear in the Transcript window. It is useful for showing messages or logging information.

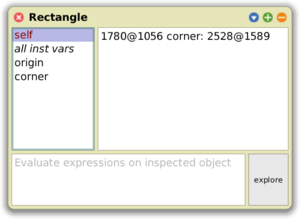

Inspector

The Inspector lets you look inside an object. It usually has two parts:

- On the left, a list of the object's internal information (its "instance variables").

- On the right, a workspace where you can type code to interact with the selected information.

You can change the values of an object's variables directly in the Inspector. You can also "drill down" to inspect other objects that are part of the current object.

Notifier and Debugger

If your program runs into an error, a Notifier window will pop up. This window shows you where the error happened and gives you options like "Debug" or "Proceed." If you choose "Debug," a full Debugger opens. The Debugger has several parts:

- The top shows the "stack," which is a list of all the methods that were running when the error happened.

- When you select a method in the stack, the middle part shows the code for that method and highlights where the error occurred.

- The bottom parts let you look at the object that received the message and the variables used in that method.

The Debugger lets you "step into" or "step over" code, which means you can run your program one step at a time to see exactly what is happening. This is very helpful for finding and fixing bugs. If an error happens because a method is missing, the Notifier might even create a basic version of the missing method for you to fill in. This allows you to fix and continue your program without restarting it, which is a very powerful way to program!

Hello World Example

The "Hello World" program is a classic first program in any language. In Smalltalk, it is very simple:

Transcript show: 'Hello, world!'.This code sends the message `show:` to the `Transcript` object, with the text `'Hello, world!'` as the argument. This makes the text appear in the Transcript window. To see it, you just need to have a Transcript window open in your Smalltalk environment.

Saving Your Work (Image-based Persistence)

Most programming systems keep your program code separate from the data it uses. When you start a program, it loads the code, and you have to load any data separately. If you do not save something, it is lost when the program closes.

Smalltalk systems are different. They often save the entire program, including all the code and all the data (objects), in one "image" file. This image file is like a snapshot of your entire Smalltalk system. When you load the image, your Smalltalk system goes back to exactly how it was when you saved it. This is very helpful for quickly continuing your work and for debugging, because you can see the program's exact state when an error happened.

Changing Everything (Level of Access)

In Smalltalk-80, almost everything can be changed while the program is running. This means you can change the programming tools themselves without restarting the system. You could even change how the language works or how it manages memory! This makes Smalltalk very flexible and powerful for programmers.

Fast Code (Just-in-time Compilation)

Smalltalk programs are usually turned into "bytecode," which is a special code that a virtual machine understands. This virtual machine then runs the code or quickly translates it into code that your computer's processor can understand directly. Smalltalk systems use clever tricks to make message sending very fast, sometimes even faster than similar actions in other languages like C++.

Different Smalltalk Versions

Many different versions of Smalltalk exist today. Some popular ones include:

OpenSmalltalk

The OpenSmalltalk VM (Virtual Machine) is a fast way to run Smalltalk programs. Several modern open-source Smalltalk versions use it. It was built from the original Squeak interpreter. The OpenSmalltalk VM can turn Smalltalk code into C language code, which then gets compiled for different computers, allowing Smalltalk programs to run on many different platforms.

Notable Smalltalk versions based on OpenSmalltalk VM are:

- Squeak: The original open-source Smalltalk that the OpenSmalltalk VM was built for. It came from Xerox PARC's Smalltalk-80 v1.

- Pharo: An open-source Smalltalk that came from Squeak, used for research and in businesses.

- Croquet: A special Smalltalk for building shared, online applications.

- Cuis Smalltalk: Another version that came from Squeak.

Other Versions

- Amber Smalltalk: Runs in web browsers using JavaScript.

- Dolphin Smalltalk: A version for Windows.

- Etoys: A visual programming system for learning, built in Squeak.

- GemStone/S: Used for databases.

- GNU Smalltalk: A version without a graphical interface, part of the GNU project.

- ObjectStudio: From Cincom.

- Scratch: A visual programming system for kids (versions before 2.0 were based on Smalltalk).

- Smalltalk/X: A descendant of the original Xerox PARC Smalltalk-80.

- VisualAge Smalltalk: From IBM.

- VisualWorks: From Cincom, a descendant of the original Xerox PARC Smalltalk-80 v2.

Related Languages

Smalltalk influenced many other programming languages, including:

- Dart

- Objective-C

- Newspeak

- Ruby

- Self

- Strongtalk

See also

In Spanish: Smalltalk para niños

In Spanish: Smalltalk para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |