One Laptop per Child facts for kids

|

|

| Formation | January 28, 2005 |

|---|---|

| Type | Non-profit |

| Headquarters | Miami, Florida, U.S. |

|

Official language

|

Multilingual |

|

Founder

|

Nicholas Negroponte |

|

Key people

|

|

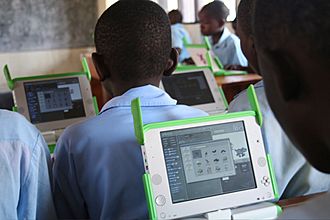

One Laptop per Child (OLPC) was a non-profit group that wanted to change education for children worldwide. Their main goal was to create and give out special, low-cost computers for learning in developing countries. They also made software and learning materials for these devices.

When the program started in 2005, a regular laptop cost more than $1,000. So, OLPC needed to make a much cheaper computer. This led to the OLPC XO Laptop, which was designed to be affordable and use little power. Companies like AMD, eBay, Google, and Marvell Technology Group helped fund the project. Other companies, like Quanta, gave support in other ways. Sadly, after not selling as many laptops as hoped, the organization closed down in 2014.

The OLPC project was talked about a lot. People praised it for being one of the first to make low-cost, low-power laptops. It even inspired other devices like Eee PCs and Chromebooks. It also helped countries agree that learning about computers is a key part of education. The laptops had special designs that worked even for children who couldn't read well in any language, especially English.

However, the project also faced criticism. Some said it focused too much on the U.S. and ignored bigger problems. Others pointed out the high total costs, lack of focus on repairs and training, and limited success. A book from 2019, The Charisma Machine, looked closely at the OLPC project.

Contents

How the OLPC Project Started

The OLPC program was inspired by the ideas of Seymour Papert. He believed that giving computers to young children would help them become fully skilled with technology. Papert and Nicholas Negroponte both worked at the MIT Media Lab. Papert compared putting computers only in a special lab to old libraries where books were chained to walls. Negroponte said sharing computers was like sharing pencils. But back then, computers were very expensive, costing over $1,500 each.

In 2005, Negroponte spoke at the World Economic Forum in Davos. He asked companies to help create a $100 laptop. He believed this would change education and bring knowledge to all children. He showed a fake model of the laptop and tried to get support from many people. Even though some, like Bill Gates, were doubtful, Negroponte got interest from companies like AMD and News Corp. He knew that making the screen cheaper was key to lowering the laptop's cost. When he met Mary Lou Jepsen, a display expert, they talked about new screen ideas. Convinced it was possible, Negroponte started the Hundred Dollar Laptop Corp.

At the 2006 Wikimania event, Jimmy Wales announced that Wikipedia would be included on the OLPC laptops. He explained that he wanted to help children in Africa get free learning materials. He also hoped his own daughter would grow up in a world where knowledge was free for everyone to use and share.

In 2006, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) also announced its support for the OLPC. They said they would work with OLPC to bring technology to schools in the poorest countries.

From 2007, the OLPC Association managed the development and delivery of the laptops. The OLPC Foundation handled fundraising, like the "Give One Get One" campaign.

Intel was part of the OLPC group for a short time in 2007. Later, Intel left because of disagreements with Negroponte. He had asked Intel to stop selling their own low-cost computers, called Classmate PCs, at very low prices.

In 2008, Negroponte thought about adding Windows XP to the laptops, even though OLPC usually used open-source software. Microsoft offered to sell Windows XP for $3 per laptop. It would be an option on the XO-1 laptops, possibly allowing users to choose between Windows and Linux. Because of this, Walter Bender, who worked on OLPC's software, left and started Sugar Labs. This new group continued to develop the open-source Sugar software that OLPC had created. However, very few countries chose to buy Windows licenses.

In 2008, OLPC lost a lot of its funding. Their yearly budget was cut from $12 million to $5 million. This led to big changes in January 2009. The development of the Sugar operating system was moved to the community. About half of the paid employees were let go. Even with these cuts, OLPC kept working on new versions of the laptops.

In 2010, OLPC moved its main office to Miami. New funding from Marvell Technology Group helped the organization. They shipped over 3 million XO Laptops to children around the world.

Challenges and Criticisms

The OLPC project faced many challenges and criticisms.

Cost of the Laptops

The project first aimed for a price of $100 per laptop. But in May 2006, Negroponte said the price would likely be around $135 or $140. By April 2010, the price was still over $200. In 2011, it was still above $209.

For many people in developing countries, spending over $200 on a laptop was a lot. In 2013, more than 10% of the world lived on less than $2 a day. This meant a laptop would cost more than a quarter of their yearly income.

John Wood, who started Room to Read (a group that builds schools and libraries), thought simpler solutions were better. He said a $2,000 library could help 400 children, costing only $5 per child. A $10,000 school could help 400-500 children. He felt these were more suitable for education in very poor areas.

Some groups suggested using recycled second-hand computers in labs as a cheaper option. But Negroponte argued that older laptops would cost too much to run.

Teacher Training and Support

The OLPC project was criticized for not providing enough technical support or training for teachers. Some said they just gave out laptops and didn't follow up. For example, in Peru, teachers were told to fix software problems by "flashing" the computer (reinstalling the software) or report hardware issues. This made teachers and students feel confused and disconnected from the laptops. Many laptops ended up not being used.

In Uruguay, only about 21.5% of teachers used the laptop daily in the classroom. In Alabama, U.S., 80.3% of students said they rarely used the computer for schoolwork. In Peru, usage dropped after a few months. Experts said that children from poorer backgrounds needed more help and guidance from teachers to use the laptops effectively for learning.

Walter Bender, a former OLPC executive, said the project needed a more complete approach. This included combining technology with ongoing community effort, teacher training, and local educational ideas.

Negroponte disagreed with the "walk away" criticism. He said that children could learn on their own with a connected laptop.

Other reasons for problems included high minimum order numbers for countries, laptops breaking easily, and not fitting local cultures.

Laptop Technology

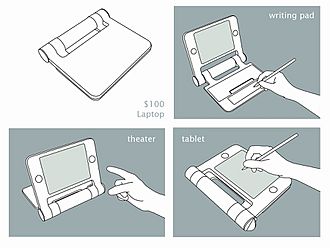

The XO laptop, also called the "$100 Laptop" or "Children's Machine," was designed to be cheap. It aimed to give children in developing countries access to knowledge and chances to "explore, experiment, and express themselves." This idea is part of constructionist learning. The laptop was designed by Yves Béhar and made by the Taiwanese company Quanta Computer.

These tough, low-power computers used flash memory instead of a hard drive. They ran a special operating system based on Fedora and used the SugarLabs Sugar user interface. They could connect to each other using a wireless mesh network. This allowed students to work together and share Internet access from one connection. The wireless range was much better than typical laptops. The XO-1 was built to be low-cost and last a long time.

In 2009, OLPC announced an updated XO, called the XO-1.5. It had a new processor and better graphics. It came with 1GB of RAM and 4 GB of storage, with an option for 8 GB. The XO-1.5 used the same screen and a more power-efficient wireless connection.

An XO-1.75 model was developed using a Marvell ARM processor. It aimed for a price below $150 and was planned for 2011.

The idea for an XO-2, which had two screens, was dropped. Instead, they focused on the XO-3.

The XO-3 concept looked like a tablet computer. It was planned to have the same inside parts as the XO 1.75. The goal was a price below $100 and a release in 2012.

At the CES in 2012, OLPC showed off the XO-3 tablet. However, in late 2012, they announced that the XO-3 would not be made. They shifted their focus to the XO-4.

The XO-4 was launched at International CES 2013. It came in two models: XO 4 and XO 4 Touch, which had a touchscreen. The XO 4 used an ARM processor for good performance and low power, while keeping the original XO laptop design.

Software Used

The laptops had an anti-theft system. This system could require each laptop to connect to a server regularly to stay working. If it didn't connect, the laptop would lock until a new signal was received. This helped prevent theft. The mass-produced laptops also prevented users from easily installing new software or changing the operating system. This was said to prevent accidental damage and help with the anti-theft system.

In 2006, OLPC faced criticism because of a secret agreement with Marvell about the wireless device. This was a problem because OLPC was supposed to be open-source friendly. Some experts, like Theo de Raadt, asked for more open information about the wireless parts.

OLPC's commitment to "Free and open source" software was questioned in 2008. They announced that large buyers could choose to add a special version of the private Windows XP operating system from Microsoft. This would be alongside the regular, free, and open Linux-based system with the SugarLabs "Sugar OS" interface. Microsoft offered Windows XP for an extra $10 per laptop. OLPC said future laptops would be able to use both systems. However, this option was not popular, and very few Windows licenses were bought. Negroponte said the debate had become a "distraction" from the main goal of helping children learn.

Common Problems (Bugs)

The organization was also criticized for not providing enough help with problems. Teachers in Peru, for example, were told to either reinstall the software or report hardware issues. This made teachers and students feel confused, and many laptops ended up not being used. Some problems with the OLPC XO-1 hardware appeared, and repairs were often neglected because parts were expensive.

On the software side, the security system sometimes locked laptops by mistake. This made them unusable until technicians unlocked them, which took a lot of time. The Sugar interface was hard for teachers to learn. Also, the mesh networking feature, which allowed laptops to connect to each other, often had problems and wasn't used much.

The OLPC XO-1 hardware couldn't connect to external monitors or projectors. Teachers also didn't have software to check students' work remotely. This meant students couldn't show their work to the whole class, and teachers had to check each laptop individually. Teachers also found the small keyboard and screen difficult to use.

Environmental Impact

Before the final design of the XO-1 hardware, OLPC was criticized for concerns about harmful materials found in most computers. OLPC said they aimed to use as many environmentally friendly materials as possible. They also said the laptop would follow strict environmental rules and use much less power than typical laptops. This would reduce its impact on the environment.

The XO-1, released in 2007, used eco-friendly materials and followed environmental rules. It used very little power, between 0.25 and 6.5 watts. The XO-1 was the first laptop to get an "EPEAT Gold level rating," which means it was very good for the environment.

How Laptops Were Given Out

The laptops were sold to governments, who then gave them out through their education departments. The goal was "one laptop per child." The laptops were given to students, like school uniforms, and stayed the child's property. The software was translated into the languages of the countries involved.

Later, OLPC also worked directly with sponsors to bring its education program to whole schools and communities. As a non-profit, OLPC needed funding so that children and their families didn't have to pay for the laptops.

Early Deliveries

About 500 early test versions were given out in mid-2006. Then, 875 working prototypes were delivered in late 2006. Full production started in November 2007. Around one million laptops were made in 2008.

Give 1 Get 1 Program

OLPC first said they wouldn't sell the XO laptop to regular customers. But later, they started the "Give 1 Get 1" (G1G1) program in November 2007. For a donation of $399 (plus shipping), people in the U.S. and Canada could get an XO-1 laptop for themselves. OLPC would then send another laptop to a child in a developing country.

About 83,500 people took part in this program. All the G1G1 laptops were delivered by April 2008.

From November to December 2008, a second G1G1 program was run through Amazon.com. This time, it aimed to be available worldwide. Laptops could be delivered to many countries in North and South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. However, this program sold far fewer laptops than the first one.

OLPC no longer sells directly to customers. Instead, it focuses on raising money.

Laptop Shipments

As of 2015, OLPC reported that 'more than 3 million laptops' had been shipped around the world.

Where OLPC Laptops Were Used

Uruguay

In October 2007, Uruguay ordered 100,000 laptops. This made Uruguay the first country to buy a large number of OLPC laptops. The first real use of the OLPC technology happened in Uruguay in December 2007. Since then, 200,000 more laptops were ordered to give one to every public school child aged 6 to 12.

Uruguay's President presented the last laptop at a school in Montevideo in October 2009. Over two years, 362,000 students and 18,000 teachers were involved. The program cost the country $260 per child, including maintenance, repairs, teacher training, and internet. The yearly cost to keep the program going was about $21 per child.

Uruguay became the first country where every primary school child received a free laptop on October 13, 2009. This was part of their Plan Ceibal (Education Connect).

Even though about 35% of all OLPC computers went to Uruguay, a 2013 study found that the laptops didn't improve reading skills. It also said that the laptops were mostly used for fun. Only 4.1% of laptops were used "all" or "most" days in 2012. The study concluded that the program had no impact on test scores in reading and math. However, more recent studies, like one from 2020, have viewed the project as a success.

United States

Originally, OLPC said the United States would not be part of the first year of the program. In 2008, Nicholas Negroponte said that "OLPC America" would likely be based in Washington, D.C., but this group was not set up. As of 2010, Birmingham, Alabama, had the largest use of OLPC laptops in the U.S. Negroponte mentioned that the changing economy made OLPC adjust its plan. He also talked about building a large group of users and helping children worldwide communicate.

Artsakh

On January 26, 2012, the prime minister of Artsakh and a business leader signed an agreement to start an OLPC program there. The program focused on elementary schools across Artsakh. The goal was to help the war-affected region get a better education. A non-profit group called the Armenian General Benevolent Union helped with support on the ground. The government of Artsakh was very keen and worked with OLPC to make the program happen.

Nigeria

In late 2007, a Nigerian company sued OLPC, claiming that the laptop's keyboard design was stolen from their patented device. OLPC said they hadn't sold any keyboards with that design and that the company had hidden facts from the court. In January 2008, a Nigerian court rejected OLPC's request to stop the lawsuit and continued to prevent OLPC from giving out laptops in Nigeria. OLPC appealed this decision.

India

In June 2006, India's Ministry of Human Resource Development rejected the OLPC idea. They said it would be too expensive for a questionable plan when public money was needed for other important things. Later, they announced plans to make their own laptops for schoolchildren, aiming for a $10 price. In 2010, a related $35 tablet called "Aakash" was shown in India and released the next year.

OLPC later supported India's own laptop efforts. In 2009, some Indian states planned to order OLPC laptops. However, as of 2010, only the state of Manipur had given out 1000 laptops.

See also

In Spanish: One Laptop per Child para niños

In Spanish: One Laptop per Child para niños

- Child computer

- Computer literacy

- Digital divide

- Digital textbook

- Dynabook

- Educational technology in sub-Saharan Africa

- Simputer

- Universal access to education

- Web (2013 film)

- World Computer Exchange

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |