Women in STEM fields facts for kids

For a long time, fields like science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) have mostly been for men. Since the 1700s, during the Age of Enlightenment, fewer women have joined these areas. Many experts and leaders are looking into why this difference between boys and girls in STEM still exists. They also want to find ways to make things more fair. STEM jobs are often well-paying and important, so it's good for everyone to have a chance to work in them.

Contents

Why are there fewer girls in STEM?

Many things can affect how young people feel about mathematics and science. This includes encouragement from parents, teachers, what they learn in school, and hands-on activities. In the United States, studies show different ideas about when boys' and girls' attitudes about math and science start to differ. Some research found not many differences in early middle school. What students hope to do for a job in math and science affects the classes they choose and how hard they work.

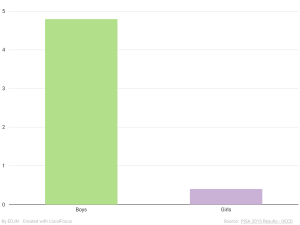

A study from 1996 in the USA found that girls might start to lose confidence in middle school. They sometimes think boys are naturally better at technology. This idea can come from the fact that men often do better in spatial skills, which are important in engineering. Spatial skills are about understanding shapes and spaces. Some experts believe boys get more practice with these skills outside school because they are often encouraged to build things. But research shows girls can learn these skills just as well with the right training.

In 1996, a study of new college students showed that men and women chose very different subjects to study. About 20% of men and only 4% of women planned to study computer science and engineering. But similar numbers of men and women planned to study biology or physical sciences. These differences in what students plan to study often lead to differences in the degrees they earn. After high school, fewer women get degrees in math, physical sciences, computer science, and engineering. The field of life science is an exception, where there is a more even mix.

How does this affect the economy?

In Scotland, many women finish STEM degrees but don't get STEM jobs, unlike men. Experts there think that if more women worked in high-skill jobs, Scotland's economy could grow by £170 million each year.

A 2017 study found that if more women studied STEM in the EU, it would help the economy grow. It could increase the money earned per person by 0.7–0.9% by 2030 and by 2.2–3.0% by 2050.

Do men and women earn different amounts?

Women who finish college often earn less than men who finish college. This is true even though everyone's earnings grew in the 1980s. Some of these pay differences are because women and men often work in different types of jobs. Among recent science and engineering graduates, women were less likely to work in science and engineering jobs than men.

There is still a pay difference between men and women in similar science jobs. This difference is even bigger for scientists and engineers who have been working longer. The highest salaries are in math, computer science, and engineering, where fewer women work. In Australia, a 2013 study showed that the pay difference between men and women in STEM jobs was 30.1%. This was an increase from 2012.

Another study found that when professors were looking to hire a lab manager, they often rated male applicants as more skilled and easier to hire. This was true even when the male and female applicants had the exact same resume. The professors were also willing to offer male applicants higher starting pay and more chances for career help.

How do stereotypes affect education?

In the U.S., about 42% of PhDs in STEM fields are earned by women. But for all fields, women earn about 52% of PhDs. Stereotypes and differences in education can cause fewer women to join STEM fields. These differences can start as early as third grade. Boys often do better in math and science, while girls do better in reading.

Women in STEM around the world

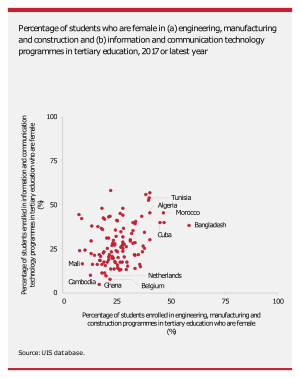

Organizations like UNESCO and the European Commission have spoken out about how few women work in STEM fields globally. It's hard to compare numbers between countries because terms for education levels, job types, and other things can be different. Even when countries use the same words, what they mean in society can be very different.

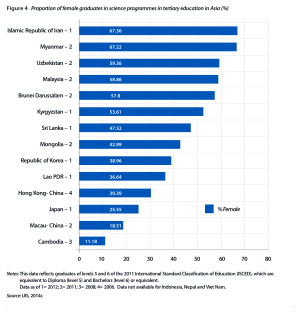

Asia

A UNESCO report from 2015 showed that about 30% of researchers worldwide were women. By 2018, this number went up to 33%. In East Asia, the Pacific, South Asia, and West Asia, only 20% of researchers were women. But in Central Asia, women made up 46% of researchers, which is much closer to equal. Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan were the only countries in Asia where women were the majority of researchers, but just barely.

| Countries | Percentage of researchers who are female |

|---|---|

| Central Asia | 46% |

| World | 30% |

| South and West Asia | 20% |

| East Asia and the Pacific | 20% |

Cambodia

In Cambodia, in 2004, only 13.9% of science students were female. In 2002, 21% of researchers in science and technology were women. These numbers are lower than in other Asian countries like Malaysia and South Korea. Cambodia's education system has a long history of being mostly for men. This comes from old Buddhist teaching practices. Girls were allowed to go to school starting in 1924. But there are still traditional ideas that men are more powerful, which affects women in school and at work.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the government is working to make things more equal for boys and girls. But old ideas about women's jobs still exist. Because of traditional views, women sometimes find it hard to stay in their jobs or get promoted. More women study science subjects like pharmacy and biology than math and physics. In engineering, the numbers vary a lot. For example, 78% of chemical engineering students are women, but only 5% of mechanical engineering students are women. In 2005, only 31% of science and engineering researchers were female.

Malaysia

In Malaysia, in 2011, 48.19% of science students were female. This number has grown a lot in the last 30 years. In Malaysia, over 50% of people working in the computer industry are women, even though this field is often mostly men. More than 70% of pharmacy students are female, while only 36% of engineering students are female. In 2011, women held 49% of research jobs in science and technology.

Mongolia

In Mongolia, in 2012, 40.2% of science students were female, and in 2018, 49% of science and technology researchers were female. Traditionally, nomadic Mongol culture was quite equal. Both women and men raised children, cared for animals, and fought. This is similar to how equal men and women are in Mongolia's workforce today. More girls than boys go to college, and 65% of college graduates in Mongolia are women. However, women earn about 19–30% less than men. People also sometimes think women are not as good at engineering as men. Fewer than 30% of computer science, construction, and engineering workers are female. But three out of four biology students are female.

South Korea

In 2012, 30.63% of science students in South Korea were female. This number has been growing since the digital revolution. The number of male and female students in most education levels is similar. But the difference is bigger in higher education. Old beliefs that women are less valuable can affect the STEM gender gap in South Korea. Like in other countries, many more women work in medicine (61.6%) than in engineering (15.4%) or other math-based STEM fields. In 2011, women made up 17% of science and technology researchers. Most women in STEM jobs in South Korea are temporary workers, meaning their jobs are not very stable. A study found that girls in South Korea scored lower on math tests and felt more worried about math than boys.

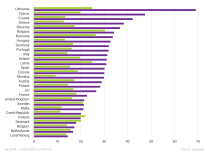

Europe

In the European Union, only about 16.7% of ICT (Information and Communication Technology) specialists are women. Only in Romania and Bulgaria do women hold more than 25% of these jobs. In 2012, women earned 47.3% of all PhDs. But they earned only 28% of PhDs in engineering, manufacturing, and construction. In computing, only 21% of PhDs were earned by women.

In 2013, men scientists and engineers made up 4.1% of all workers in the EU, while women made up only 2.8%. In more than half of the countries, women are less than 45% of scientists and engineers. But things are getting better. Between 2008 and 2011, the number of women scientists and engineers grew by 11.1% each year, while the number of men grew by only 3.3%.

In 2018, Mariya Gabriel, a European leader, announced plans to get more women into digital jobs. She wants to challenge stereotypes, teach digital skills, and support women who start their own businesses. In 2018, Ireland started linking money for research to how well universities reduce differences between boys and girls.

North America

United States

According to the National Science Foundation, women make up 43% of the U.S. science and engineering workforce for those under 75. For those under 29, women are 56% of this workforce. About one in seven engineers is female. However, only 28% of people working in science and engineering jobs are women. This means not all women trained in these fields get jobs in them. Women hold 58% of jobs related to science and engineering.

Women in STEM jobs earn much less than men, even when they have similar education and age. On average, men in STEM jobs earn $36.34 per hour, while women earn $31.11 per hour.

| Bachelor's degree field | Men (%) | Women (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture/natural resources | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| Architecture | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| Computer and information sciences | 6.9 | 1.8 |

| Engineering/ engineering technologies | 13.8 | 3.2 |

| Biology/ biomedical sciences | 5.1 | 6.2 |

| Mathematics/statistics | 1.5 | 0.8 |

| Physical/social sciences | 11.1 | 14.3 |

| Health studies | 2.6 | 9.9 |

| STEM total | 43.8 | 38.0 |

| Business | 22.7 | 17.6 |

| Education | 4.0 | 11.6 |

| Other | 29.5 | 32.8 |

| Non-STEM total | 56.2 | 62.0 |

| Total graduates (%) | 29.4 | 37.5 |

| Total graduates (thousands) | 6403.3 | 8062.5 |

More women than men get bachelor's degrees overall, and also in STEM fields as defined by the National Center for Education Statistics. However, fewer women are in specific fields like Computer Sciences, Engineering, and Mathematics. Along with women, racial/ethnic minorities in the U.S. are also underrepresented in STEM.

Asian women are more represented in STEM fields in the U.S. than African American, Hispanic, Pacific Islander, and Native American women. In universities, these minority women make up less than 1% of permanent teaching jobs in top U.S. universities. This is despite making up about 13% of the total U.S. population. A 2015 study suggested that attitudes towards hiring women for these jobs have gotten better. There was a 2:1 preference for women in STEM when qualifications were equal.

African American women

According to Kimberly Jackson, unfair treatment and stereotypes can stop women of color, especially Black women, from studying STEM. Stereotypes about Black women's intelligence and work can make them feel less confident in STEM. Some schools, like Spelman College, are trying to change these ideas and help more African-American women get involved in STEM. Students of color, especially Black students, can face difficulties in STEM majors. They might experience unfriendly environments, small everyday slights, and a lack of support.

Latin American women

A 2015 study estimated that Latin American women made up only 1% of the U.S. tech workforce. A 2018 study of 50 Latin American women who started technology companies found that 20% were Mexican, 14% were bi-racial, and 4% were Venezuelan.

Canada

A 2019 study in Canada found that 44% of first-year STEM students are women. This is compared to 64% of non-STEM students. Women who leave STEM courses often go to related fields like healthcare or finance. A study found that only 20–25% of computer science students in Canadian colleges are women. Also, only about 1 in 5 of those women will graduate from these programs.

Women are less likely to choose a STEM program, even if they are good at math. Young men with lower math grades are more likely to go into STEM fields than young women with higher math grades.

Awards and competitions

Fewer women have won top awards in STEM fields compared to men. Between 1901 and 2017, for Nobel Prizes:

- Physics: 2 women out of 207 winners

- Chemistry: 4 women out of 178 winners

- Physiology/Medicine: 12 women out of 214 winners

- Economic Sciences: 1 woman out of 79 winners

Maryam Mirzakhani was the first woman and first Iranian to win the Fields Medal in 2014. The Fields Medal is a very important math prize, and it has been given out 56 times in total.

Fewer female students take part in big STEM competitions like the International Mathematical Olympiad. In 2017, only 10% of the participants were female. The winning South Korean team of six had only one female member.

New technology and women

Computers are everywhere now, and this has helped break down old ideas about what boys and girls prefer to do with technology. Both boys and girls use the internet and email a lot. They have learned skills and feel confident using many tech tools for school and personal use in high school. But there is still a gap in how many girls sign up for computer science classes, which goes down from grades 10 to 12. Globally, only 3% of graduates in information and communications technology programs are women.

A review of UK patent applications in 2016 found that more new inventions were being registered by women. But most female inventors worked in areas often seen as "female," like designing bras or makeup. In 2016, Russia had the highest percentage of patents filed by women, at about 16%.

Why are there so few women in STEM?

There are many reasons why fewer women work in STEM fields. These reasons can be about society, how people think, or even ideas about natural abilities. Often, these reasons are connected.

Societal reasons

Unfair treatment

Women in STEM fields might leave their jobs because of unfair treatment. This can be obvious or hidden. Women are twice as likely to leave science and engineering jobs than men. In the 1980s, studies showed that people generally judged women unfairly.

A 2012 study sent emails to professors at top U.S. universities. The emails asked to meet about graduate school. The study found that professors were less likely to respond to emails from women and ethnic minorities compared to white men. In another study, science professors were given applications for a lab manager job. All applications were the same, but some had male names and some had female names. The professors rated the male candidates as more skilled and easier to hire, even though the applications were identical. This shows that if people know a student's gender, they might think the student has traits that fit stereotypes for that gender.

The head of UNESCO, Audery Azoulay, said that even today, "women and girls are sidelined in science-related fields because of their gender." A 2017 survey found that women in STEM jobs are more likely to experience unfair treatment at work than men. About half of women in STEM have faced gender-based unfairness. This includes men being paid more for the same job, being treated like they are not good enough, or being made fun of. Some women also said that in workplaces with mostly men, being a woman felt like a barrier to their success.

Stereotypes

Stereotypes are fixed ideas about what someone in a STEM field should look and act like. These ideas can cause people to overlook skilled individuals who don't fit the mold. The typical scientist or engineer is often thought of as male. Women in STEM might not fit this idea, so they could be overlooked or treated unfairly. The "Role Congruity Theory of Prejudice" says that if a gender doesn't seem to fit a certain job, it can lead to negative judgments. Also, negative stereotypes about women's math skills can make people undervalue their work or discourage them from staying in STEM.

Job ads for male-dominated careers often use words like "leader" or "goal-oriented," which are linked to male stereotypes. The "Social Role Theory" says that men are expected to be strong leaders, and women are expected to be caring. These expectations can affect hiring decisions. A 2009 study found that women were described with more caring words, and men with more leading words, in recommendation letters. These caring words were linked to fewer hiring decisions in universities.

Women entering jobs usually for men might face negative stereotypes. But these stereotypes don't seem to stop women as much as similar stereotypes might stop men from choosing jobs usually for women. Historically, women have rushed into male-dominated jobs when they had the chance. It's very rare for a job to change from being mostly for women to mostly for men. The few times it has happened, like in medicine, the job had to be seen as "masculine" before men would join.

Men in jobs usually for women might face stereotypes about their masculinity. But they might also get certain benefits. In 1992, it was suggested that women in male-dominated jobs often hit a "glass ceiling." This means it's hard for them to reach the top. But men in female-dominated jobs might experience a "glass escalator." This means they can move up quickly in a job mostly done by women.

Lack of support

Women in STEM might leave their jobs if they don't get enough support. This includes not being invited to important meetings, unfair rules against women, jobs that are not flexible, feeling like they have to hide pregnancies, and struggling to balance family and work. Women in STEM who have children often need childcare or have to take a long break from work. If a family can't afford childcare, the mother often gives up her career to stay home. This is partly because women are often paid less in their jobs. If the man earns more, he goes to work, and the woman gives up her career.

Maternity leave is another issue. In the U.S., the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) allows 12 weeks of unpaid leave for new mothers. This is one of the shortest leaves in developed countries. All developed countries except the U.S. give mothers some paid time off. If a new mother doesn't have money saved or outside help, she might not be able to take her full leave. Few companies allow men to take paternity leave, and it might be shorter than women's maternity leave. Longer paternity leaves for men could let women go back to work while their partners stay home with the children.

Not enough role models

In 1996, women made up almost 50% of non-permanent teaching jobs in engineering and science education. But they were only 10% of permanent professors. Also, the number of female department heads in medical schools did not change from 1976 to 1996. Women who do get permanent jobs might feel like they are the only one of their kind. They might not get support from co-workers and could face problems from peers and bosses. Research suggests that girls might not be interested in STEM because of stereotypes about STEM jobs and workplaces. Women are more affected by these stereotypes.

The "leaky pipeline"

The "leaky pipeline" is a way to describe how women leave STEM fields at different points in their careers. In the U.S., out of 2,000 high school students, 1944 were in high school in Fall 2014. If there were equal numbers of boys and girls, about 60 boys and 62 girls would be considered "gifted." When comparing enrollment to the population of 20–24 year olds, 880 out of 1000 original women and 654 out of 1000 original men will go to college (2014). In their first year, 330 women and 320 men will say they want to study science or engineering. But only 142 women and 135 men will actually get a bachelor's degree in science or engineering. And only 7 women and 10 men will get a PhD in science or engineering.

Psychological reasons

Not enough interest

A study found that men often prefer working with things, and women prefer working with people. When interests were grouped, men showed stronger interests in realistic and investigative areas. Women showed stronger interests in artistic, social, and conventional areas. Differences favoring men were also found for specific interests in engineering, science, and math.

In a 3-year study, students who switched from STEM to non-STEM majors often said it was because other subjects offered better education or matched their interests more. This was the most common reason (46%) for female students. The second most common reason for switching was a reported loss of interest in their chosen STEM major. Also, 38% of female students who stayed in STEM majors worried that other subjects might fit their interests better. Another survey of people who left science showed that 30% of women said "other fields more interesting" was their reason for leaving.

Good math skills don't always make women interested in a STEM career. A Canadian study found that even young women who are very good at math are much less likely to enter a STEM field than young men who are equally good or even less good at math.

Not enough confidence

One of the biggest problems for girls is during their teenage years. One reason for girls' lack of confidence might be teachers who are not good or who have unfair ideas about what boys and girls can do. Teachers' ideas about their students' abilities can create an unfair learning environment and stop girls from continuing in STEM. They can also pass these ideas on to their students. Studies show that how teachers interact with students affects girls' involvement in STEM. Teachers often give boys more chances to solve problems by themselves. But they tell girls to follow the rules. Teachers are also more likely to take questions from boys, while telling girls to wait. This is partly because of ideas that boys should be active, and girls should be quiet.

Before 1985, girls had fewer chances to do lab work than boys. In middle and high school, science, math, mechanics, and computer classes are mainly taken by boys and often taught by male teachers. Not having enough chances in STEM fields can lead to low self-esteem in math and science. Low self-esteem can stop people from entering science and math fields.

One study found that women avoid STEM fields because they think they are not good enough. The study suggested that encouraging girls to take more math classes could fix this. Among students planning to study STEM, 35% of women said they left calculus because they didn't understand the material. Only 14% of men said the same. This difference is thought to come from women's lower confidence, not their actual skill. This study shows that women and men have different levels of confidence, and confidence is linked to how well people do in STEM fields. Another study found that when men and women with the same math skills were asked to rate their own ability, women rated their ability much lower. Programs that help reduce math anxiety or increase confidence have a good effect on women continuing in STEM.

Stereotype threat

Stereotype threat happens when someone worries that their actions will confirm a negative stereotype about their group. This worry creates extra stress, which uses up brain power and makes it harder to do well. People can experience stereotype threat whenever they are tested in an area where there's a negative stereotype about a group they belong to. Stereotype threat makes girls and women do worse in math and science. This leads to their abilities being underestimated. Studies have found that differences in performance between boys and girls disappear if students are told there are no gender differences on a math test. This shows that the learning environment can really affect how well someone does.

A study was done to see how stereotype threat affects women studying STEM. There were three groups. One group of women was told that men had done better than women on the same calculus test they were about to take. The next group was told men and women had done equally well. The last group was told nothing about how men had performed. Women did best when there was no mention of gender. They did worst when told men had performed better. For women to go into STEM, they need more confidence in math and science.

Innate versus learned skill

Some studies suggest that STEM fields, especially physics, math, and philosophy, are seen by both teachers and students as needing more natural talent than skills that can be learned. Along with the idea that women have less of this natural talent, this can lead to women being seen as less qualified for STEM jobs. A study found that without strong calculus skills, women cannot do as well as men in any STEM field. This leads to fewer women choosing careers in these fields. A high number of women who do start a STEM career don't continue after taking Calculus I, which is seen as a class that filters out students from the STEM path.

There have been some controversial statements about natural ability and success in STEM. For example, Lawrence Summers, a former president of Harvard University, suggested that differences in natural ability at high levels could cause population differences. He later stepped down. A former Google engineer, James Damore, wrote a memo suggesting that differences between men and women were a reason for the gender imbalance in STEM. He was fired for this memo.

Comparative advantage

A 2019 study suggested that fewer women in STEM fields might be because of "comparative advantage." This means that even though girls might score a little lower on math tests, their much better reading skills mean they perform better overall than boys. This might make women more likely to study subjects related to humanities than math.

However, most people agree that the current difference between boys and girls in STEM is not good for the economy.

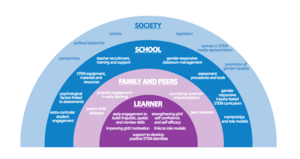

How can we get more women in STEM?

Many things can explain why there are few women in STEM careers. Anne-Marie Slaughter, a former U.S. government leader, has suggested ways for workplaces to help women succeed while balancing work and family life. These ideas could also help women in universities and research.

Social-psychological help

Researchers have tried different ways to help women deal with stereotype threat when their math and science skills are being tested. The goal is to boost women's performance and encourage more of them to stay in STEM careers.

One simple way is to teach people about stereotype threat. Researchers found that women who learned about stereotype threat and how it could affect their math performance did as well as men on a math test. This was true even when stereotype threat was present. These women also did better than women who were not taught about stereotype threat.

Role models

One way to help with stereotype threat is by showing role models. One study found that women who took a math test given by a female experimenter did not do worse than women whose test was given by a male experimenter. Also, it wasn't just having a female experimenter there. It was learning about her math skills that helped protect the participants from stereotype threat.

Other studies suggest that role models don't have to be people in charge. They can also be friends. One study found that girls in all-girl groups did better on a math task than girls in mixed-gender groups. This was because girls in the all-girl groups had more access to positive role models, like their female classmates who were good at math.

Similarly, another experiment showed that highlighting group achievements helped women with stereotype threat. Female participants who read about successful women, even if their successes weren't directly about math, did better on a math test. This was compared to participants who read about successful companies.

A study looking at textbook pictures found that women understood a chemistry lesson better when the text had a picture of a female scientist. They understood it less when it had a picture of a male scientist.

Other experts say that getting women into STEM is one challenge, and keeping them there is another. They suggest that both male and female role models can help get women into STEM. But female role models are better at helping women stay in these fields. Female teachers can also be role models for young girls. Studies show that having female teachers helps girls feel better about STEM and makes them more interested in STEM careers.

Self-affirmation

Researchers have looked at how "self-affirmation" can help with stereotype threat. This is when you remind yourself of your good qualities. One study found that women who thought about a personal value before facing stereotype threat did as well on a math test as men. They also did as well as women who didn't experience stereotype threat. Another study found that a short writing exercise helped college students in a physics class. When they wrote about their most important values, the difference in grades between boys and girls got much smaller, and women's grades went up. Experts believe this works because it helps people see themselves as complex individuals, not just through a harmful stereotype.

Organized efforts

To get more women into STEM, experts believe efforts should start in elementary and middle schools. Differences between boys and girls are clear by kindergarten. Many children have already formed ideas about math and their future jobs. A study of high school and middle school students shows a difference in science and math test scores between boys and girls.

Another way to reduce the gender gap is to create communities and opportunities outside of school. For example, having special programs for women, women-only colleges, and links between high school and college STEM programs can help close the gap. Research shows that the gender gap in STEM might be due to an unsupportive culture that hurts women's career growth. Because of this, women in the U.S. are not well-represented in permanent teaching jobs and leadership roles.

Organizations like Girls Who Code, StemBox, Blossom, Engineer Girl, Girls Can Code in Afghanistan, @IndianGirlsCode, Stanford's Women in Data Science Initiative, and Kode with Klossy (started by supermodel Karlie Kloss) encourage girls and women to explore STEM fields that are often male-dominated. Many of these groups offer summer programs and scholarships. Other efforts, like Girls’ Day in the Netherlands, let girls aged 10-15 visit tech companies to learn about STEM.

The U.S. government has also funded similar projects. The Department of State created TechGirls and TechWomen. These programs teach girls and women from the Middle East and North Africa skills important in STEM fields. There is also the TeachHer Initiative by UNESCO, which aims to close the gender gap in STEM education and careers. This initiative also stresses the importance of after-school activities for girls. That's why Dell Technologies teamed up with Microsoft and Intel in 2019 to create Girls Who Game (GWG). This after-school program uses Minecraft: Education Edition to teach girls communication, teamwork, creativity, and critical thinking skills.

Current campaigns to get more women into STEM fields include the UK's WISE. There are also mentoring programs like the Million Women Mentors initiative, which connects girls and young women with STEM mentors. GlamSci and Verizon's #InspireHerMind project are also working on this. The U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy during the Obama administration worked with the White House Council on Women and Girls to increase women's participation in STEM. This was part of the "Educate to Innovate" campaign.

In August 2019, the University of Technology Sydney announced that women applying to certain engineering and IT programs would need a lower minimum entry score. This also applies to anyone with a long-term educational disadvantage.

Programs like FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology) are always working to close the gender gap in computer science. FIRST is a robotics and research program for students from kindergarten through high school. The activities and competitions in the program are usually about current STEM problems. A report shows that about 13.7% of men and 2.6% of women entering college hope to major in engineering. In contrast, 67% of men and 47% of women who took part in the FIRST program tend to major in engineering.

See also

In Spanish: Mujeres en campos de CTIM para niños

In Spanish: Mujeres en campos de CTIM para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |