Sophie Germain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sophie Germain

|

|

|---|---|

Marie-Sophie Germain

|

|

| Born |

Marie-Sophie Germain

1 April 1776 Paris, France

|

| Died | 27 June 1831 (aged 55) Paris, France

|

| Known for | Elasticity theory number theory Mean curvature Sophie Germain prime Sophie Germain's theorem Germain−Lagrange plate equation |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematician, physicist, and philosopher |

| Academic advisors | Carl Friedrich Gauss (epistolary correspondent) |

| Notes | |

|

Other name: Auguste Antoine Le Blanc

|

|

Marie-Sophie Germain (born April 1, 1776 – died June 27, 1831) was a brilliant French mathematician, physicist, and philosopher. Even though her parents didn't want her to study math at first, and society made it hard for girls to learn, Sophie taught herself. She read books from her father's library, including works by famous thinkers like Euler. She also wrote letters to important mathematicians such as Lagrange, Legendre, and Gauss. She even used a fake name, Monsieur LeBlanc, to hide that she was a girl.

Sophie was a pioneer in a field called elasticity theory, which studies how materials bend and stretch. She won a big award from the Paris Academy of Sciences for her work on this topic. Her ideas also helped other mathematicians with a famous problem called Fermat's Last Theorem. Because it was hard for women to have careers in math back then, she worked on her own. Before she died, Gauss suggested she get an honorary degree, but it never happened. Sophie Germain passed away on June 27, 1831, from breast cancer. Years later, a street and a girls' school were named after her to honor her amazing achievements. The Academy of Sciences also created the Sophie Germain Prize in her memory.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Her Family and Home

Sophie Germain was born on April 1, 1776, in Paris, France. Her father, Ambroise-François, was a rich silk merchant. In 1789, he became a representative for the middle class in the États-Généraux. This was a big meeting that later turned into the Constitutional Assembly. So, Sophie probably heard many talks about politics and ideas between her father and his friends. Her family was always well-off, which helped Sophie later in life.

Sophie had two sisters, Angélique-Ambroise and Marie-Madeline. Her mother was also named Marie-Madeline. Because there were so many "Maries" in the family, she was usually called Sophie.

Discovering Mathematics

When Sophie was 13, the Bastille prison was stormed, and the city became very unsafe. This meant Sophie had to stay inside her home. To keep herself busy, she started exploring her father's library. There, she found a book called L'Histoire des Mathématiques by J. E. Montucla. She was fascinated by the story of Archimedes, a famous mathematician, and how he died while studying geometry.

Sophie realized that if math could be so exciting to Archimedes, it was worth learning. So, she read every math book in her father's library. She even taught herself Latin and Greek so she could read important works by people like Sir Isaac Newton and Leonhard Euler. She also enjoyed books by Étienne Bézout and Jacques Antoine-Joseph Cousin. Later, Cousin even visited Sophie at her home and encouraged her studies.

Sophie's parents didn't like her sudden interest in math. They thought it wasn't proper for a girl. At night, they would take away her warm clothes and fire from her room to stop her from studying. But after they left, Sophie would light candles, wrap herself in blankets, and continue doing math. After a while, her mother even started to secretly support her.

Learning at École Polytechnique

In 1794, when Sophie was 18, a new school called the École Polytechnique opened. As a woman, Sophie couldn't attend classes there. However, the school made its "lecture notes available to all who asked." Students also had to "submit written observations." Sophie got the notes and started sending her work to Joseph Louis Lagrange, a professor at the school. She used the name of a former student, Monsieur Antoine-Auguste Le Blanc. She later told Gauss that she was "fearing the ridicule attached to a female scientist." When Lagrange saw how smart M. Le Blanc's work was, he asked to meet him. This forced Sophie to reveal her true identity. Luckily, Lagrange didn't mind that Sophie was a woman, and he became her mentor.

Early Work in Number Theory

Writing to Legendre

Sophie first became interested in number theory in 1798. This was when Adrien-Marie Legendre published his book, Essai sur la théorie des nombres. After studying his work, she started writing letters to him about number theory and later about elasticity. Legendre even included some of Sophie's ideas in a later edition of his book. He called her work "very ingenious."

Writing to Gauss

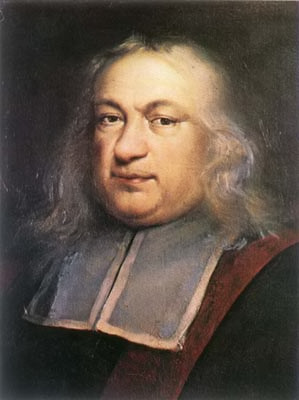

Sophie's interest in number theory grew again when she read Carl Friedrich Gauss's important book, Disquisitiones Arithmeticae. After three years of working through the problems and trying to prove some of the ideas herself, she wrote to Gauss. She was still using the name M. Le Blanc. Her first letter, sent on November 21, 1804, talked about Gauss's book and shared some of her own ideas about Fermat's Last Theorem.

Around 1807, during the Napoleonic wars, French soldiers were in the German town where Gauss lived. Sophie worried that he might be in danger, like Archimedes had been. So, she wrote to General Pernety, a friend of her family, asking him to make sure Gauss was safe. General Pernety sent an officer to check on Gauss. Gauss was fine, but he was confused when Sophie's name was mentioned.

Three months later, Sophie told Gauss her real identity. Gauss's letters show that he truly admired Sophie. Even though Gauss thought highly of Sophie, he often took a long time to reply to her letters and didn't always review her work closely. Eventually, his interests moved away from number theory, and their letters stopped in 1809. Sophie and Gauss were friends through letters, but they never met in person.

Work in Elasticity

Trying for the Academy Prize

After her letters with Gauss stopped, Sophie became interested in a contest. The Paris Academy of Sciences was offering a prize for work related to Ernst Chladni's experiments. Chladni had shown how metal plates vibrate and create patterns. The Academy wanted a mathematical explanation for how elastic surfaces vibrate and how it matched experiments. Lagrange had said that solving this problem would need a whole new type of math. This scared away all but two people: Denis Poisson and Sophie Germain. Then Poisson became a judge for the contest, leaving Sophie as the only person trying to win.

Sophie started working on the problem in 1809. Legendre helped her by giving her equations and research. She sent in her paper in late 1811 but didn't win. The judges felt that the "true equations of the movement were not established," even though her experiments showed "ingenious results."

More Tries for the Prize

The contest was extended for two more years, and Sophie decided to try again. At first, Legendre helped her, but then he stopped. Sophie's paper in 1813 still had some math mistakes, especially with certain types of integrals. She only received an honorable mention because the basic ideas of her theory "were not established." The contest was extended again, and Sophie started her third attempt. This time, she talked with Poisson. In 1814, he published his own work on elasticity but didn't mention Sophie's help. He had worked with her and, as a judge, had seen her work.

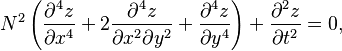

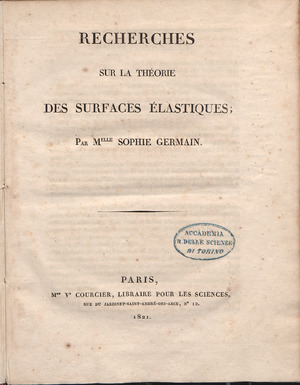

Sophie submitted her third paper, Recherches sur la théorie des surfaces élastiques, using her own name. On January 8, 1816, she became the first woman to win a prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences! She didn't go to the ceremony to get her award. Even though Sophie finally won the prize, the Academy wasn't completely satisfied. Sophie had found the correct differential equation for vibrating plates, but her method didn't perfectly match experiments because she used an incorrect equation from Euler. Here is Sophie's final equation for how a flat plate vibrates:

where N2 is a constant number.

Even after winning the prize, Sophie still couldn't attend the Academy's meetings. This was because of a rule that kept women out, unless they were wives of members. Seven years later, this changed when she became friends with Joseph Fourier, a secretary of the Academy. He got her tickets so she could attend the sessions.

Later Work on Elasticity

Sophie published her prize-winning essay herself in 1821. She mostly did this to show her work against Poisson's. In the essay, she pointed out some mistakes in his method.

In 1826, she sent a new version of her 1821 essay to the Academy. This new version tried to make her work clearer. The Academy found the paper "inadequate and trivial." However, they didn't want to treat her like a male colleague and just reject it. So, Augustin-Louis Cauchy, who reviewed her work, told her to publish it, and she did.

Another one of Sophie's works on elasticity was published after she died in 1831. It was called Mémoire sur la courbure des surfaces. In this research, she used something called mean curvature.

Later Work in Number Theory

New Interest in Numbers

Sophie's best work was in number theory, especially her ideas about Fermat's Last Theorem. In 1815, after the elasticity contest, the Academy offered a prize for a proof of Fermat's Last Theorem. This made Sophie interested in number theory again. She wrote to Gauss after ten years of no contact.

In her letter, Sophie said that number theory was her favorite subject. She explained a plan for a general proof of Fermat's Last Theorem. She also included a proof for a special case. Sophie's letter to Gauss showed she had made great progress. She asked Gauss if her way of thinking about the theorem was worth continuing. Gauss never replied.

Her Work on Fermat's Last Theorem

Fermat's Last Theorem is a famous math problem. It can be split into two parts. Sophie came up with an important idea, now called "Sophie Germain's theorem":

Sophie used this idea to prove the first part of Fermat's Last Theorem for all odd prime numbers less than 100. Later, another mathematician, L. E. Dickson, used Sophie's theorem to prove the first part for all odd primes less than 1700.

In a paper that was never published, Sophie showed that any numbers that might break Fermat's theorem for powers greater than 5 would have to be incredibly huge, around 40 digits long! Sophie didn't publish this work. Her amazing theorem is known only because it was mentioned in a footnote in Legendre's book on number theory. He used it to prove Fermat's Last Theorem for the power of 5. Sophie also proved or almost proved several other math ideas that were later given to other mathematicians or rediscovered years later.

Work in Philosophy

Besides math, Sophie also studied philosophy and psychology. She wanted to organize facts and turn them into rules that could explain how people think and how societies work. A famous philosopher named Auguste Comte greatly admired her ideas.

Two of her philosophy books, Pensées diverses and Considérations générales sur l'état des sciences et des lettres, aux différentes époques de leur culture, were published after she died. Her nephew, Armand-Jacques Lherbette, helped gather her writings and publish them. Pensées is a history of science and math with Sophie's thoughts. In Considérations, the book Comte liked, Sophie argued that there are no real differences between science and the humanities (like art and literature).

Final Years and Legacy

In 1829, Sophie found out she had breast cancer. Even though she was in pain, she kept working. In 1831, a math journal published her paper on the curvature of elastic surfaces. She also published an article about how elastic solids move. Sophie Germain passed away on June 27, 1831, at her home in Paris.

Even with all her amazing achievements, Sophie's death certificate listed her as a "property holder," not a "mathematician." But not everyone overlooked her work. In 1837, six years after Sophie's death, the University of Göttingen was discussing honorary degrees. Gauss said that Sophie "proved to the world that even a woman can accomplish something worthwhile in the most rigorous and abstract of the sciences and for that reason would well have deserved an honorary degree."

Honors and Memorials

Memorials to Sophie

Sophie Germain's grave is in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. To celebrate 100 years after her birth, a street and a girls' school were named after her. A plaque was also placed on the house where she died. The school has a statue of her that was ordered by the Paris City Council.

In January 2020, a company called Satellogic launched a small satellite named in honor of Sophie Germain.

Math Honors Named After Her

- A Sophie Germain prime is a prime number p where 2p + 1 is also a prime number.

- The Germain curvature is another name for mean curvature, which is a concept in geometry.

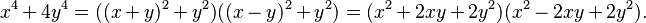

- Sophie Germain's identity is a math rule that states for any numbers x and y:

How People Saw Her Work

What People Thought Then

When Sophie's prize-winning essay was published in 1821, people's reactions were polite but not overly excited. However, some critics praised it highly. Cauchy said her essay "deserved the attention of mathematicians." Sophie was also mentioned in a book called "Woman in Science." This book quoted mathematician Claude-Louis Navier saying that her work was "a work which few men are able to read and which only one woman was able to write."

Gauss certainly thought highly of her. He understood that it was especially hard for a woman to succeed in mathematics during that time.

What People Think Now

Today, most people agree that Sophie Germain was a very talented mathematician. However, because she didn't have formal schooling, she sometimes lacked the strong basic training she needed to be even better. One expert said that her work in elasticity "suffered generally from an absence of rigor," meaning it wasn't always perfectly precise. This was a big problem when she was judged by other mathematicians, not just admired as a young genius.

Despite these issues, Sophie's work was very important for developing the general theory of elasticity. It's interesting to note that when the Eiffel Tower was built, the names of 72 great French scientists were carved on it. Sophie Germain's name was not among them, even though her work was important for building the tower. Some believe she was left out because she was a woman.

Regarding her early work in number theory, some experts say she was good at algebra but might not have fully understood some very complex ideas. They also say that mathematicians who liked her sometimes praised her instead of giving her helpful criticism, which might have held back her math development. However, others recognize that Sophie "provided imaginative and provocative solutions to several important problems." Some even suggest that her lack of formal training might have given her unique ways of thinking. Her biographers summarize it well: "All the evidence argues that Sophie Germain had a mathematical brilliance that never reached fruition due to a lack of rigorous training available only to men."

Sophie Germain Prize

The Sophie Germain Prize is an award given every year by the Academy of Sciences in Paris. It honors a French mathematician for their research in the basic ideas of mathematics. This award, which is €8,000, was started in 2003.

See also

In Spanish: Sophie Germain para niños

In Spanish: Sophie Germain para niños

- Proof of Fermat's Last Theorem for specific exponents

- Sophie Germain Counter Mode

- Sophie Germain prime

- Sophie Germain Prize

- Sophie Germain's theorem

- Timeline of women in science

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |