Dorothy Hodgkin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Dorothy Hodgkin

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot

12 May 1910 |

| Died | 29 July 1994 (aged 84) Ilmington, Warwickshire, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Sir John Leman Grammar School |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Thomas Lionel Hodgkin

(m. 1937) |

| Children | Luke, Elizabeth, and Toby |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biochemistry X-ray crystallography |

| Thesis | X-ray crystallography and the chemistry of the sterols (1937) |

| Doctoral advisor | John Desmond Bernal |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Other notable students |

|

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin (born May 12, 1910 – died July 29, 1994) was a brilliant British chemist. She won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her amazing work. Dorothy made a special technique called X-ray crystallography much better. This helped her figure out the exact shapes of important molecules in living things. This was very important for understanding how living things work.

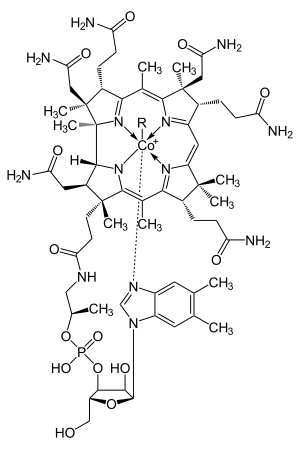

Some of her most famous discoveries include confirming the structure of penicillin. This was a very important medicine. She also figured out the structure of vitamin B12. For this discovery, she won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964. She was only the third woman to ever win this award. Later, in 1969, after 35 years of hard work, Dorothy also figured out the structure of insulin.

Dorothy used her birth name, "Dorothy Crowfoot," for many years. After she married Thomas Lionel Hodgkin, she started using "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin." Many places, like the Royal Society, simply call her "Dorothy Hodgkin."

Contents

Early Life and Education

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot was born in Cairo, Egypt. She was the oldest of four daughters. Her parents worked in North Africa and the Middle East. They were involved in colonial administration and later became archaeologists. Dorothy came from a family of archaeologists.

Her parents were John Winter Crowfoot and Grace Mary (Molly) Crowfoot. The family lived in Cairo during the winter. They returned to England each year to avoid the hot Egyptian summers. In 1914, when Dorothy was four, her mother left her and her younger sisters with their grandparents in England. Her mother returned to her husband in Egypt.

Even though they were often apart, her parents supported her. Her mother especially encouraged Dorothy's interest in crystals. Dorothy first showed this interest at age 10. In 1923, Dorothy and her sister studied pebbles they found in streams. They used a portable kit to analyze minerals.

In 1921, Dorothy's father enrolled her in the Sir John Leman High School in Beccles, England. She was one of only two girls allowed to study chemistry there. When she was 13, she visited her parents in Khartoum, Sudan. Her father was the head of Gordon College there.

A distant cousin, chemist Charles Harington, encouraged her interest in chemistry. He recommended a biochemistry book to her. Her parents continued to work abroad part of the year. They returned to England for several months each summer.

In 1928, Dorothy joined her parents at an archaeological site in Jerash, Jordan. She drew detailed patterns of mosaics from ancient churches. She even continued these drawings while starting her studies at Oxford. She also analyzed glass pieces from the site. Her careful attention to detail in these drawings was similar to her later work in chemistry. She loved archaeology so much that she thought about becoming an archaeologist instead of a chemist.

Dorothy developed a strong interest in chemistry from a young age. Her mother, who was a skilled botanist, supported her scientific interests. For her 16th birthday, her mother gave her a book on X-ray crystallography. This book helped her decide what she wanted to do in the future. A family friend, A.F. Joseph, who was also a chemist, further encouraged her.

Her school did not teach Latin, which was required to enter Oxford University. Her headmaster gave her special lessons. This allowed her to pass the entrance exam for Oxford. When asked about her childhood heroes, Dorothy named three women. First was her mother, Molly. The others were medical missionary Mary Slessor and Margery Fry, the head of Somerville College.

Higher Education and Early Research

In 1928, at age 18, Dorothy entered Somerville College, Oxford. She studied chemistry there. In 1932, she graduated with top honors. She was only the third woman at Oxford to achieve this.

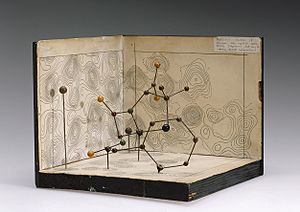

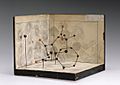

Later that year, she began working on her PhD at Newnham College, Cambridge. Her supervisor was John Desmond Bernal. It was then that she realized how powerful X-ray crystallography could be. This technique could figure out the structure of proteins. She worked with Bernal on using this technique for the first time on a biological substance, pepsin. Dorothy is largely credited for the pepsin experiment. However, she always said that Bernal took the first photographs and gave her important ideas. She earned her PhD in 1937. Her research was on X-ray crystallography and the chemistry of sterols.

Career and Major Discoveries

In 1933, Dorothy received a research fellowship from Somerville College. In 1934, she moved back to Oxford. She started teaching chemistry using her own lab equipment. The college made her its first chemistry tutor in 1936. She held this job until 1977.

In the 1940s, one of her students was Margaret Roberts. Margaret later became Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Margaret Thatcher respected Dorothy so much that she hung a portrait of her former teacher in her office. Dorothy, however, was a lifelong supporter of the Labour Party.

In 1953, Dorothy and her colleagues were among the first to see the model of the double helix structure of DNA. This model was built by Francis Crick and James Watson. It was based on data from Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. Dorothy and her team drove from Oxford to Cambridge to see this groundbreaking model.

Dorothy became a "reader" (a senior academic position) at Oxford in 1957. The next year, she got a modern laboratory. In 1960, she was appointed the Royal Society's Wolfson Research Professor. This position provided her salary and research funds. She held this role until 1970. She was also a fellow at Wolfson College, Oxford, from 1977 to 1983.

Unlocking Steroid Structures

Dorothy was especially known for figuring out the 3D shapes of important biological molecules. In 1945, she and her colleague C.H. Carlisle published the first such structure of a steroid. This was cholesteryl iodide, a type of cholesterol. She had been working on cholesteryls since her PhD studies.

Solving the Penicillin Structure

In 1945, Dorothy and her team, including biochemist Barbara Low, solved the structure of penicillin. At the time, many scientists thought it had a different structure. Dorothy's work showed that it contained a special ring called a β-lactam ring. This work was finally published in 1949.

Discovering Vitamin B12 Structure

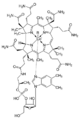

In 1948, Dorothy first worked with vitamin B12. She was able to create new crystals of it. Vitamin B12 had only been discovered earlier that year. Its structure was mostly unknown. When Dorothy found it contained cobalt, she realized X-ray crystallography could figure out its shape. The molecule was very large, and most of its atoms were unknown. This made it a huge challenge.

From these crystals, she guessed there was a ring structure. This was because the crystals showed different colors when viewed from different angles (pleochroic). She later confirmed this using X-ray crystallography. The study of B12 that Dorothy published was called as important "as breaking the sound barrier" by another famous scientist, Lawrence Bragg. The final structure of B12, which earned Dorothy the Nobel Prize, was published in 1955.

The Long Journey to Insulin Structure

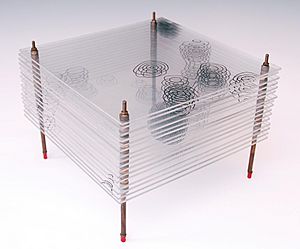

Insulin was one of Dorothy's most amazing research projects. It started in 1934 when she received a small sample of crystalline insulin. This hormone fascinated her because it has such complex and widespread effects in the body. However, at that time, X-ray crystallography was not advanced enough to handle a molecule as complex as insulin. She and others spent many years making the technique better.

It took 35 years after her first photograph of an insulin crystal for the techniques to be ready. Finally, in 1969, Dorothy and her team of young, international scientists were able to figure out the structure of insulin for the first time.

Dorothy's work with insulin was very important. It helped make it possible to mass-produce insulin. This meant it could be used widely to treat both type one and type two diabetes. She worked with other labs doing insulin research, offering advice and traveling the world to talk about insulin. Solving the structure of insulin had two big impacts for diabetes treatment. It made mass production possible. It also allowed scientists to change insulin's structure to create even better medicines for patients.

Personal Life and Beliefs

Personality and Influence

Dorothy Hodgkin was soft-spoken, gentle, and modest. But beneath this, she had a strong determination to reach her goals. She inspired great loyalty in her students and colleagues. Even the newest members of her team called her simply "Dorothy." Her studies of important biological molecules set high standards for her field. She made huge contributions to understanding how these molecules work in living systems.

Health Challenges

In 1934, at age 24, Dorothy started having pain and swelling in her hands. After an infection following the birth of her first child, she was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. This condition would get worse over time, causing pain and deformities in her hands and feet. In her later years, Dorothy often used a wheelchair. Despite this, she remained active in her scientific career.

Marriage and Family

In 1937, Dorothy Crowfoot married Thomas Lionel Hodgkin. He was a historian's son. He taught adult education classes in mining communities in England. Thomas was sometimes a member of the Communist Party. He later wrote important books on African politics and history. He became a well-known lecturer at Balliol College, Oxford.

During World War II, Thomas's health was too poor for military service. He continued working, returning to Oxford on weekends. Dorothy stayed in Oxford, working on penicillin. The couple had three children: Luke (born 1938), Elizabeth (born 1941), and Toby (born 1946). Their children were very talented. Luke became a mathematician. Elizabeth followed her father's career path. Toby studied botany and agriculture. Thomas Hodgkin spent a lot of time in West Africa. He was a big supporter of the new independent African nations.

Aliases and Recognition

Dorothy published her work as "Dorothy Crowfoot" until 1949. Then, she was asked to use her married name for a chapter she wrote in a book called The Chemistry of Penicillin. By then, she had been married for 12 years, had three children, and had been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

After that, she published as "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin." This was the name used by the Nobel Foundation when she received her award. For simplicity, the Royal Society and Somerville College often refer to her as "Dorothy Hodgkin."

International Connections

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Dorothy made strong connections with scientists in other countries. She worked with researchers at the Institute of Crystallography in Moscow, in India, and with Chinese scientists in Beijing and Shanghai. These Chinese groups were also working on the structure of insulin.

Her first visit to China was in 1959. She traveled there seven more times over the next 25 years. Her last visit was a year before she died. A memorable visit was in 1971. The Chinese group had independently solved the structure of insulin. They did it later than Dorothy's team, but with even more detail.

Political Views and Activities

Because of Dorothy's political activities and her husband's connection to the Communist Party, she was banned from entering the US in 1953. She was only allowed to visit the country with special permission.

In 1961, Thomas became an advisor to Kwame Nkrumah, the President of Ghana. Thomas spent long periods in Ghana. Dorothy was in Ghana with her husband when they heard she had won the Nobel Prize.

Dorothy learned from her mother, Molly, to care about social inequalities. She was determined to help prevent armed conflicts. Dorothy became especially worried about the threat of nuclear war. In 1976, she became president of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs. She held this position longer than anyone else. She stepped down in 1988. This was the year after a treaty banned certain nuclear weapons. In 1987, she accepted the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet government. This was for her work for peace and disarmament.

Later Life and Death

Due to the long distance, Dorothy decided not to attend the 1987 International Union of Crystallography Congress in Australia. However, despite her increasing weakness, she surprised everyone by going to Beijing for the 1993 Congress. She was warmly welcomed there.

She passed away in July 1994 after a stroke. She died at her husband's home in the village of Ilmington, England.

Honours and Awards

Achievements During Her Life

- By 1945, she successfully described the 3D arrangement of atoms in penicillin.

- Dorothy won the 1964 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. She is the only British woman scientist to have won a Nobel Prize in any of the three sciences (Physics, Chemistry, Medicine).

- In 1965, she was appointed to the Order of Merit. She was only the second woman in science to receive this honor.

- She was the first woman to receive the very respected Copley Medal.

- In 1947, she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). She also became an EMBO Member in 1970.

- Dorothy was the Chancellor of the University of Bristol from 1970 to 1988. She received an honorary Science Degree from the University of Bath in 1978.

- In 1958, she was elected an Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- In 1966, she received the Iota Sigma Pi National Honorary Member award for her important contributions.

- She became a foreign member of the USSR Academy of Sciences in the 1970s.

- In 1982, she received the Lomonosov Medal from the Soviet Academy of Sciences.

- In 1987, she accepted the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet government. She was the first woman to receive the Copley Medal and the Lenin Peace Prize.

- An asteroid (5422) discovered in 1982 was named "Hodgkin" in her honor in 1993.

- In 1983, Dorothy received the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art.

Legacy and Impact

- British Commemorative Stamps: Dorothy was one of five "Women of Achievement" chosen for a set of stamps in 1996. In 2010, for the 350th anniversary of the Royal Society, she was the only woman in a set of stamps celebrating ten of the Society's most famous members. She was featured alongside scientists like Isaac Newton and Ernest Rutherford.

- Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship: The Royal Society awards the Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship. This is for excellent scientists early in their careers who need flexible working hours. This might be due to parenting, caring for others, or health reasons.

- Buildings Named After Her: Council offices in London and buildings at the University of York, Bristol University, and Keele University are named after her. The science building at her old school, Sir John Leman High School, is also named in her honor.

- The New Elizabethans: In 2012, Dorothy was featured in the BBC Radio 4 series The New Elizabethans. This series celebrated people whose actions had a big impact on life in the UK during Queen Elizabeth II's reign.

- Chemical Breakthrough Award: In 2015, Dorothy's 1949 paper on the structure of penicillin was honored. It received a Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award. This award recognized her groundbreaking use of X-ray crystallography to find the structure of complex natural products like penicillin.

- Dorothy Hodgkin Memorial Lecture: Since 1999, the Oxford International Women's Festival has held an annual lecture in her honor.

- Famous Quote: Dorothy once said, "I believe in perfecting the world and trying to do everything to improve things, but not because I know what's to come of it."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin para niños

In Spanish: Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin para niños