Maurice Wilkins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Maurice Wilkins

|

|

|---|---|

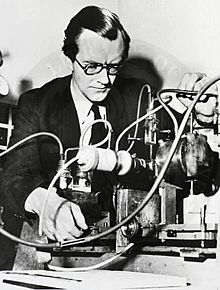

Maurice Wilkins with one of the cameras he developed specially for X-ray diffraction studies at King's College London

|

|

| Born |

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins

15 December 1916 Pongaroa, New Zealand

|

| Died | 5 October 2004 (aged 87) Blackheath, London, England

|

| Education | King Edward's School, Birmingham |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge (MA) University of Birmingham (PhD) |

| Known for | X-ray diffraction, DNA |

| Spouse(s) | Ruth Wilkins (div.) Patricia Ann Chidgey

(m. 1959) |

| Children | 5 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biophysics Physics |

| Institutions | King's College London University of Birmingham University of California, Berkeley University of St Andrews |

| Thesis | Phosphorescence decay laws and electronic processes in solids (1940) |

| Doctoral advisor | John Randall |

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist. He won the Nobel Prize for his important work on the structure of DNA.

Wilkins' research covered many areas of science. He helped us understand phosphorescence, how to separate isotopes, and how microscopes work. He also contributed to X-ray diffraction and helped develop radar.

His most famous work was at King's College London. There, he used X-ray diffraction to study DNA. His early studies in 1948–1950 produced the first clear X-ray images of DNA. He showed these images at a conference in 1951.

Later, in 1951–52, Wilkins got even clearer "B form" X-ray images of DNA. These images looked like an "X". He sent them to James Watson and Francis Crick. Watson wrote that Wilkins had "extremely excellent X-ray diffraction photographs" of DNA.

In 1953, Wilkins was given a very clear image of "B" form DNA. This image, called Photo 51, was made by Raymond Gosling in 1952. It had been put aside by Rosalind Franklin as she was leaving King's College. Wilkins showed this image to Watson.

This image, along with the news that Linus Pauling had suggested a wrong structure for DNA, encouraged Watson and Crick to restart their work. With more information from Wilkins and Franklin's research, Watson and Crick correctly described DNA's double-helix structure in 1953.

Wilkins continued to check and improve the Watson–Crick DNA model. He also studied the structure of RNA. In 1962, Wilkins, Crick, and Watson won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. They received it for their discoveries about the structure of nucleic acids (like DNA) and how they help transfer information in living things.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Maurice Wilkins was born in Pongaroa, New Zealand, on December 15, 1916. His father, Edgar Henry Wilkins, was a medical doctor. When Maurice was six, his family moved to Birmingham, England.

He attended Wylde Green College and then King Edward's School, Birmingham from 1929 to 1934. In 1935, Wilkins went to St John's College, Cambridge. He studied physics and earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1938.

Later, he became a PhD student at the University of Birmingham. He worked with John Randall. In 1940, Wilkins received his PhD for his work on phosphorescence.

Career and Research

Working After the War: 1945–1950

During World War II, Maurice Wilkins helped improve radar screens in Birmingham. He then worked on separating isotopes for the Manhattan Project in the United States from 1944 to 1945.

After the war, in 1945, Wilkins joined John Randall at the University of St Andrews. Randall then moved to King's College London in 1946. He set up a new Biophysics Unit there. This unit aimed to use physics methods to solve biology problems. Wilkins became the Assistant Director of this new unit.

Wilkins oversaw many projects and worked on new types of microscopy. The Biophysics Unit moved into new laboratories in 1952. Wilkins wrote an article for Nature magazine about these new departments.

Discovering DNA's Structure: Phase One

At King's College, Wilkins began working on X-ray diffraction of DNA. He used DNA samples from a Swiss scientist named Rudolf Signer. This DNA was much better than what had been used before.

Wilkins found he could make thin threads from this DNA solution. These threads had DNA molecules arranged in a very orderly way. This was perfect for X-ray diffraction. Wilkins and his student Raymond Gosling took X-ray photographs of these DNA threads. The photos showed that the long DNA molecule had a regular, crystal-like structure.

Gosling later said it was a "eureka moment" when they saw the clear spots on the film. They realized that if DNA was the genetic material, then genes could "crystallize." This first X-ray work happened in mid-1950. One of these photos, shown in Naples in 1951, made James Watson very interested in DNA. Wilkins also told Francis Crick about the importance of DNA.

Wilkins ordered new X-ray equipment. He also suggested that Rosalind Franklin, who was about to join the lab, should work on DNA.

Discovering DNA's Structure: Phase Two (1951–1952)

Rosalind Franklin arrived at King's College in early 1951. Wilkins was on holiday at the time. When he returned, he expected to work with Franklin on the DNA project he had started. However, Franklin believed the DNA X-ray work was her project alone. This caused some tension between them.

By November 1951, Wilkins had evidence that DNA, both in cells and purified, had a spiral (helical) shape. He shared his results with Watson and Crick. This information, along with what Watson heard from Franklin, encouraged Watson and Crick to build their first DNA model. However, Franklin told them their model was wrong. She knew the outer part of the DNA molecule had to be water-loving (hydrophilic).

In early 1952, Wilkins got much clearer X-ray patterns. He showed them to Sir William Lawrence Bragg, who agreed they strongly suggested a helical structure for DNA. These patterns were very inspiring.

Franklin focused on the "A-form" of DNA, which was less hydrated. Wilkins worked on the "B-form," which was more hydrated. Wilkins faced challenges because Franklin had the best DNA samples. He got new samples, but they were not as good.

In early 1953, Watson visited King's College. Wilkins showed him a high-quality X-ray image of the B-form DNA. This image is now known as Photo 51. Franklin had produced it in March 1952.

Knowing that Linus Pauling was also working on DNA and had published a wrong model, Watson and Crick made a strong effort to figure out DNA's structure. They also got useful information from Franklin's research reports. Watson and Crick published their proposed DNA double helix structure in the journal Nature in April 1953. In their paper, they thanked Wilkins and Franklin for their "unpublished results and ideas."

The first Watson-Crick paper appeared on April 25, 1953. The scientists from Cambridge and King's College agreed to publish their related work in three papers in Nature.

After 1953

After the DNA double helix was published in 1953, Wilkins continued his research. He led a team that did many careful experiments. Their work helped prove that the double helix model was correct for different living things. It showed that the double helix structure is universal.

Wilkins became the deputy director of the MRC Biophysics Unit at King's in 1955. He then became the director from 1970 to 1972.

Awards and Honours

Maurice Wilkins received many awards and honors for his scientific contributions.

- In 1959, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). This is a very high honor for scientists in the UK.

- In 1960, he received the Albert Lasker Award.

- In 1962, he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE).

- Also in 1962, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Watson and Crick for discovering the structure of DNA.

- In 1964, he became an EMBO Member.

From 1969 to 1991, Wilkins was the first President of the British Society for Social Responsibility in Science.

In 2000, King's College London opened the Franklin-Wilkins Building. This building honors the important work of Dr. Franklin and Professor Wilkins at the college.

A DNA sculpture outside Clare College, Cambridge in England also honors their work. It states that "The double helix model was supported by the work of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins."

In 2006, the Centre for Molecular Biodiscovery at the University of Auckland was renamed the Maurice Wilkins Centre.

Personal Life

Maurice Wilkins was married twice. His first marriage ended in divorce. He married his second wife, Patricia Ann Chidgey, in 1959. They had four children: Sarah, George, Emily, and William. He had five children in total.

Before World War II, he was involved in anti-war activities. He published his autobiography, The Third Man of the Double Helix, in 2003.

See also

In Spanish: Maurice Wilkins para niños

In Spanish: Maurice Wilkins para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |