Conservation of mass facts for kids

The Law of Conservation of Mass is a basic rule in science. It says that in a closed system, the total amount of mass stays the same. This means mass cannot be created or destroyed. It can only change its form or move around.

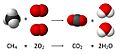

For example, during any chemical reaction, the total mass of the starting materials (called reactants) will always equal the total mass of the new materials (called products). Imagine you burn a piece of wood. The mass of the ash, smoke, and gases produced will be the same as the mass of the original wood and the oxygen used for burning.

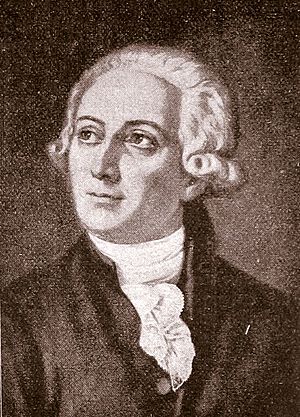

This important law is used in many areas like chemistry and physics. Antoine Lavoisier discovered it for chemical reactions in the late 1700s. His work helped change alchemy into modern chemistry.

In very special cases, like with huge amounts of energy (such as in nuclear reactions), mass and energy can be seen as related. This is explained by Einstein's famous equation E=mc². But for most everyday chemical reactions, the Law of Conservation of Mass is very accurate.

Contents

History of the Law of Mass Conservation

Early Ideas About Mass

Ancient Greek thinkers had an important idea: "Nothing comes from nothing." This meant that what exists now has always existed. They believed no new matter could just appear.

- Empedocles (around 490–430 BC) said that nothing can come from what is not, and nothing can be completely destroyed.

- Epicurus (341–270 BC) also wrote that the universe and everything in it has always been the way it is now, and always will be.

Later Discoveries

The Jain philosophy, an ancient Indian belief system, also teaches that the universe and its parts, like matter, cannot be destroyed or created. A text from the 2nd century AD, called Tattvarthasutra, states that a substance is permanent, but its forms can change.

A similar idea was stated by Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī (1201–1274), a Persian scientist. He wrote that "A body of matter cannot disappear completely. It only changes its form, condition, composition, color and other properties and turns into a different complex or elementary matter."

Lavoisier's Experiments

The Law of Conservation of Mass was clearly shown and proven by Antoine Lavoisier in the late 18th century. He did careful experiments, especially with burning materials. He showed that when something burns, the total mass of the substances before burning is the same as the total mass of the substances after burning. This was a huge step forward for chemistry.

Images for kids

-

Combustion reaction of methane. Here, 4 atoms of hydrogen, 4 atoms of oxygen, and 1 of carbon are present before and after the reaction. The total mass after the reaction is the same as before the reaction.

See also

In Spanish: Ley de conservación de la materia para niños

In Spanish: Ley de conservación de la materia para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |