Jocelyn Bell Burnell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jocelyn Bell Burnell

|

|

|---|---|

Bell Burnell in 2009

|

|

| 83rd President of the Royal Astronomical Society | |

| In office 2002–2004 |

|

| Preceded by | Nigel Weiss |

| Succeeded by | Kathryn Whaler |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Susan Jocelyn Bell

15 July 1943 Lurgan, County Armagh, Northern Ireland |

| Education |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | Discovering pulsars (1967) |

| Spouse(s) |

Martin Burnell

(m. 1968; div. 1993) |

| Children | 1 |

| Awards |

|

| Honours | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | The Measurement of radio source diameters using a diffraction method (1968) |

| Doctoral advisor | Antony Hewish |

Dame Susan Jocelyn Bell Burnell (born 15 July 1943) is a famous Northern Irish physicist. While she was a student working on her PhD, she made an amazing discovery in 1967: the first radio pulsars. This discovery was so important that it led to the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974. However, Jocelyn Bell Burnell herself was not given the award.

Bell Burnell has held many important positions. She was the president of the Royal Astronomical Society from 2002 to 2004. She also led the Institute of Physics from 2008 to 2010. From 2018 to 2023, she was the Chancellor of the University of Dundee.

In 2018, she received the Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics. This prize came with $3 million (about £2.3 million). She decided to use all of this money to create a special fund. This fund helps female, minority, and refugee students who want to become research physicists. The Institute of Physics manages this fund.

In 2021, Bell Burnell was awarded the Copley Medal, one of the oldest and most important science awards. She was only the second woman to receive it. In 2025, her image was featured on a stamp in Ireland, celebrating women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics).

Contents

Early Life and Education

Jocelyn Bell Burnell was born in Lurgan, County Armagh, Northern Ireland. Her parents were M. Allison and G. Philip Bell. She grew up in their country home, called "Solitude," with her younger brother and two younger sisters. Her father was an architect who helped design the Armagh Planetarium. When she visited the planetarium, the staff encouraged her to think about a career in astronomy. She also loved reading her father's books about astronomy.

She attended the Preparatory Department of Lurgan College from 1948 to 1956. At that time, boys could study technical subjects like science, but girls were usually expected to study subjects like cooking. Bell Burnell was able to study science only after her parents and others spoke up and challenged the school's rules.

After failing an important exam, her parents sent her to The Mount School in York, England. This was a Quaker girls' boarding school where she finished her high school education in 1961. She was very impressed by her physics teacher, Mr. Tillott. She said he showed her how easy physics could be if you understood a few key ideas.

She then went to the University of Glasgow and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in physics in 1965. After that, she went to New Hall, Cambridge, where she earned her PhD in 1969.

At Cambridge, she worked with her supervisor, Antony Hewish, and others. They built a special radio telescope called the Interplanetary Scintillation Array. This telescope was used to study quasars, which are very bright objects in space that had just been discovered.

Discovering Pulsars

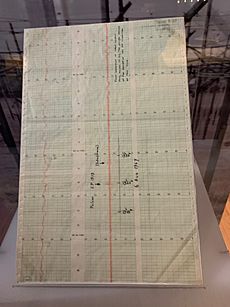

On 28 November 1967, while she was a student at Cambridge, Bell Burnell noticed something unusual. It was a "bit of scruff" on her chart-recorder papers. These papers showed signals from space. The signal had actually appeared in data from August, but it took her three months to find it because she had to check the papers by hand.

She realized that the signal was pulsing very regularly, about once every 1.3 seconds. They jokingly called the source "Little Green Man 1" (LGM-1). After several years, scientists understood that this source (now known as PSR B1919+21) was a rapidly spinning neutron star. This amazing discovery was later featured in the BBC Horizon TV series.

In a 2020 lecture, she shared how the media reacted to the pulsar discovery. She said interviews often focused on her personal life, asking about her hair color or boyfriends, while her supervisor was asked about the science. A science reporter for The Daily Telegraph shortened "pulsating radio source" to pulsar, and the name stuck.

After her PhD, she worked at several universities and observatories. She was at the University of Southampton (1968–1973), University College London (1974–1982), and the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh (1982–1991). She also taught for the Open University for many years. From 1986 to 1991, she was the project manager for the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii. She became a Professor of Physics at the Open University from 1991 to 2001.

Bell Burnell was also a visiting professor at Princeton University and the Dean of Science at the University of Bath (2001–2004). She was the President of the Royal Astronomical Society from 2002 to 2004. In 2007, she was a visiting professor of astrophysics at the University of Oxford. She was also the President of the Institute of Physics from 2008 to 2010. In 2018, she became the Chancellor of the University of Dundee.

Nobel Prize Discussion

Jocelyn Bell Burnell did not receive the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974, which caused some discussion. She had spent two years helping to build the telescope and was the one who first noticed the unusual signal. She often checked huge amounts of data by hand every night. Bell Burnell later said she had to be very persistent in reporting the signal because her supervisor, Antony Hewish, first thought it was just interference.

The scientific paper announcing the discovery of pulsars had five authors. Bell's supervisor, Antony Hewish, was listed first, and Bell was listed second. The Nobel Prize was awarded to Hewish and another astronomer, Martin Ryle. Some scientists, like Sir Fred Hoyle, felt that Bell should have been included.

In 1977, Bell Burnell said that she believed Nobel Prizes should not usually be given to students, unless it was a very special case. The Nobel committee said they were honoring Ryle and Hewish for their important work in radio-astrophysics, especially Hewish's role in discovering pulsars.

Feryal Özel, another astrophysicist, explained Bell Burnell's contributions: "She helped build the equipment she used to make the observation. She is the one who noticed it. She is the one who argued it's a real signal." Özel added that when a student takes such a lead in a project, it's hard to ignore their contribution.

In later years, Bell Burnell shared her thoughts that "the fact that I was a graduate student and a woman, together, lowered my standing in terms of receiving a Nobel prize." The decision about who receives the Nobel Prize for the pulsar discovery is still talked about today.

Awards and Honors

Jocelyn Bell Burnell has received many important awards and honors for her scientific work.

Awards

- Albert A. Michelson Medal (1973)

- J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Prize (1978)

- Beatrice M. Tinsley Prize (1986)

- Herschel Medal (1989)

- Magellanic Premium (2000)

- Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (2003)

- Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (2004)

- Grote Reber Medal (2011)

- Royal Medal of the Royal Society (2015)

- Women of the Year Prudential Lifetime Achievement Award (2015)

- Institute of Physics President's Medal (2017)

- Grande Médaille of the French Academy of Sciences (2018)

- Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics (2018). She gave all the prize money to a fund that helps women, minority, and refugee students become physics researchers.

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (2021)

- Copley Medal of the Royal Society (2021)

- Karl Schwarzschild Medal (2021)

- Prix Jules Janssen (2022)

- Matteucci Medal (2022)

- Cunningham Medal (2023)

- Hawking Fellowship (2024)

Honors

- In 1999, she was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE).

- In 2007, she was promoted to Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE). This means she is now called "Dame."

- In 2012, she became an Honorary Member of the Royal Irish Academy.

- In 2013, she was named one of the 100 most powerful women in the UK by BBC Radio 4.

- In 2014, she was recognized as one of the BBC's 100 women.

- In 2014, she became the first woman to be elected President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

- In 2016, the Institute of Physics renamed an award for young female physicists the Jocelyn Bell Burnell Medal and Prize.

- In 2020, a painting of her was added to the collection at the Royal Society headquarters.

- In 2020, the BBC included her in a list of important but lesser-known British female scientists.

- In 2025, she was appointed to the Order of the Companions of Honour.

In July 2022, Ulster Bank in Northern Ireland featured Bell Burnell on their new £50 banknote. She said she is very keen on encouraging more women to choose careers in science.

Species Named in Her Honor

A new type of sea slug, called Cadlina bellburnellae, was named after Jocelyn Bell Burnell.

Personal Life

Bell Burnell is the house patron for Burnell House at Cambridge House Grammar School. She has worked hard to improve the number and standing of women in science jobs, especially in physics and astronomy.

Quaker Activities

Since her school days, she has been an active member of the Quaker community. She has held important roles within the Quaker organization. She has also spoken about her personal religious beliefs and how they connect with her scientific work. In 2013, she wrote a book called A Quaker Astronomer Reflects: Can a Scientist Also Be Religious?, where she explored how science and faith can go together.

Family Life

In 1968, Jocelyn Bell married Martin Burnell. They later divorced in 1993. She worked part-time for many years while raising their son, Gavin Burnell. Gavin is now a scientist who studies physics at the University of Leeds.

See also

In Spanish: Jocelyn Bell Burnell para niños

In Spanish: Jocelyn Bell Burnell para niños

- Timeline of women in science

- Nobel Prize controversies

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |