Fred Hoyle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Fred Hoyle

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 24 June 1915 Gilstead, Bingley, West Riding of Yorkshire, England

|

| Died | 20 August 2001 (aged 86) Bournemouth, England

|

| Alma mater | Emmanuel College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Coining the phrase 'Big Bang' Steady-state theory Stellar nucleosynthesis theory Triple-alpha process Panspermia Hoyle state Hoyle's fallacy Hoyle's model B2FH paper Hoyle–Narlikar theory Bondi–Hoyle–Lyttleton accretion |

| Spouse(s) |

Barbara Clark

(m. 1939) |

| Children |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Institutions | Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge |

| Academic advisors | Rudolf Peierls Maurice Pryce Philip Worsley Wood |

| Doctoral students | John Moffat Chandra Wickramasinghe Cyril Domb Jayant Narlikar Leon Mestel Peter Alan Sweet Sverre Aarseth |

| Other notable students | Paul C. W. Davies Douglas Gough |

| Influenced | Jocelyn Bell Burnell Jayant Narlikar Donald D. Clayton |

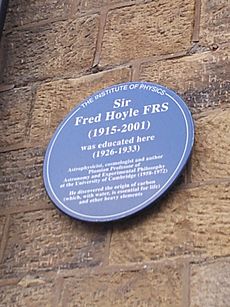

Sir Fred Hoyle (June 24, 1915 – August 20, 2001) was an English astronomer. He developed the idea of stellar nucleosynthesis. This theory explains how stars create heavier elements. He also helped write the important B2FH paper.

Hoyle had some ideas that were different from most scientists. For example, he did not believe in the "Big Bang" theory. He actually came up with the name "Big Bang" on BBC Radio. Instead, he supported the "steady-state model" of the universe. He also thought that life on Earth might have come from space, a theory called panspermia. Fred Hoyle also wrote science fiction books and plays. He spent most of his career at the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge. He was its director for six years.

Contents

About Fred Hoyle

Early Life and Education

Fred Hoyle was born in Gilstead, near Bingley, England. His father was a violinist and worked in the wool trade. His mother was a pianist. Fred went to Bingley Grammar School. He then studied mathematics at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. As a young boy, he sang in his local church choir.

In 1936, he won the Mayhew Prize for his studies.

Career Highlights

In 1940, Hoyle left Cambridge to work for the Admiralty. He did research on radar during World War II. He helped develop ways to find the height of enemy planes. He also worked on ways to stop radar-guided guns. During this time, he met other scientists like Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold. They had many talks about the universe.

His war work allowed him to visit North America. There, he learned about supernova explosions. He also learned about nuclear physics. He saw a link between supernovae and nuclear explosions. This made him think about how elements are made in stars. He later published a key paper on this idea in 1954.

Hoyle also formed a group at Cambridge to study how elements are made in ordinary stars. He noticed that a process called the triple-alpha process would work much better if the carbon-12 nucleus had a special energy level. Nuclear physicists had not found this level yet. Hoyle visited a physics group at Caltech. He convinced them to look for this special energy level, which they found. This discovery, called the Hoyle state, helped explain how carbon is made in stars.

After the war, in 1945, Hoyle returned to Cambridge University. He became a lecturer at St John's College, Cambridge. From 1945 to 1973, he became a top expert in astrophysics. He had many new and original ideas. In 1958, he became a professor at Cambridge. In 1967, he became the first director of the Institute of Theoretical Astronomy. This institute became one of the best in the world for astrophysics.

Hoyle was knighted in 1972, which means he was given the title "Sir." He left his positions at Cambridge in 1972 and 1973. After leaving Cambridge, Sir Fred Hoyle wrote many popular science and science fiction books. He also gave lectures around the world. He helped plan and open the Anglo-Australian Telescope in New South Wales.

Later Life and Passing

After leaving Cambridge, Hoyle moved to the Lake District. He enjoyed hiking and writing books. He also continued to work on scientific ideas, though some were not widely accepted. In 1997, he fell into a ravine while hiking. He was found about twelve hours later. He was in the hospital for two months with health problems. After this, his health declined. He suffered several strokes and passed away in Bournemouth in 2001.

Scientific Ideas and Contributions

How Elements Are Made in Stars

Fred Hoyle wrote the first two important research papers on how stars create chemical elements heavier than helium. In 1946, he showed that the centers of stars get very hot. At these high temperatures, elements like iron can become very common.

In 1954, Hoyle published another key paper. He showed that elements between carbon and iron are made by specific nuclear fusion reactions inside massive stars. These stars are like onions, with different elements being made in layers. This idea is now widely accepted.

In the mid-1950s, Hoyle led a group of scientists in Cambridge. This group included William Alfred Fowler, Margaret Burbidge, and Geoffrey Burbidge. They worked together to explain how all the chemical elements in the universe were created. This field is now called nucleosynthesis.

In 1957, this group published the famous B2FH paper. It explained how elements are made through different nuclear processes. This paper was so important that it became the main reference for nucleosynthesis for many years.

Hoyle's 1954 paper also used an interesting idea. It was later called the anthropic principle. He was trying to figure out how stars make carbon. He calculated that a specific nuclear reaction, the triple-alpha process, would only work if the carbon nucleus had a very exact energy level. Since there is a lot of carbon in the universe, which allows for life, Hoyle believed this reaction must work. Based on this, he predicted the exact energy level of carbon-12. Later experiments proved he was right.

Many people were surprised that Fred Hoyle did not win the Nobel Prize for Physics. His co-worker, William Alfred Fowler, won it in 1983.

Disagreement with the Big Bang Theory

Fred Hoyle agreed that the universe was expanding. This idea was supported by Edwin Hubble's observations. However, Hoyle did not agree with the idea that the universe had a beginning. He felt that the idea of a universe starting from nothing was not scientific.

Instead, Hoyle, along with Thomas Gold and Hermann Bondi, proposed the "Steady State theory" in 1948. This theory suggested that the universe is eternal and always looks the same. Even though galaxies move apart, new matter is constantly created between them. This fills the space, making the universe appear unchanging, like a flowing river. The individual water molecules move, but the river itself stays the same.

Hoyle was a strong critic of the Big Bang theory. He even gave it the name "Big Bang" during a BBC radio show in 1949. Some people thought he used the name to make fun of the theory. But Hoyle said he just wanted to create a clear image for his radio audience. He also believed that scientists liked the Big Bang theory because it sounded like the story of creation in the Bible.

Over time, more and more evidence supported the Big Bang theory. For example, the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in the 1960s. Also, the way young galaxies and quasars are spread out in the universe supported the Big Bang. Most scientists eventually accepted the Big Bang theory. However, Fred Hoyle never accepted it. He continued to work on his own ideas, like the "quasi-steady state cosmology" in 1993.

Life from Space (Panspermia)

In his later years, Hoyle became a strong critic of the idea that life started on Earth by itself. With his colleague Chandra Wickramasinghe, Hoyle suggested that the first life on Earth came from space. This idea is called panspermia. They believed that life, like viruses, could travel through the universe on comets. They also thought that new viruses arriving from space could influence evolution on Earth.

Hoyle and Wickramasinghe also suggested that some outbreaks of illnesses on Earth came from space. They even thought the 1918 flu pandemic might have been caused by a virus from cometary dust. Most experts do not agree with this idea.

In his books Evolution from Space, Hoyle argued that the chance of a simple living cell forming by itself on Earth was extremely small. He famously compared it to a "tornado sweeping through a junk-yard might assemble a Boeing 747 from the materials therein." This idea is known as "Hoyle’s Fallacy." Even though Hoyle said he was an atheist, his ideas led him to believe that "a superintellect has monkeyed with physics." This means he thought some intelligent force had designed the universe.

Media Appearances

Fred Hoyle gave a series of radio talks about astronomy for the BBC in the 1950s. These talks were later put into a book called The Nature of the Universe. He wrote many other popular science books too.

In a 2004 TV movie called Hawking, Fred Hoyle was played by Peter Firth. The movie showed a fictional meeting where Stephen Hawking challenged Hoyle's ideas.

Honours and Legacy

Fred Hoyle received many awards and honours for his work. These include:

- Being elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1957.

- The Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1968).

- The Bruce Medal (1970).

- A Knighthood in 1972.

- The Royal Medal (1974).

- The Balzan Prize for Astrophysics (1994).

- The Crafoord Prize (1997).

Several things have been named after him:

- The Hoyle Building at the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge.

- Asteroid 8077 Hoyle.

- A type of bacteria called Janibacter hoylei.

- A road in Bingley, called Sir Fred Hoyle Way.

- The Institute of Physics Fred Hoyle Medal and Prize.

His personal collection, including his papers, photos, and even his walking boots, is kept at St John's College Library.

See also

In Spanish: Fred Hoyle para niños

In Spanish: Fred Hoyle para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |