William Roy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Roy

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | 4 May 1726 Carluke, Scotland

|

| Died | 1 July 1790 (aged 64) London, England

|

| Known for | The survey of Scotland. The survey linking Britain and France. |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1785) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Surveying |

William Roy (born May 4, 1726 – died July 1, 1790) was a Scottish soldier, mapmaker, and historian. He was very good at using new science and technology to create super accurate maps of Great Britain. His most famous work is often called Roy's Map of Scotland.

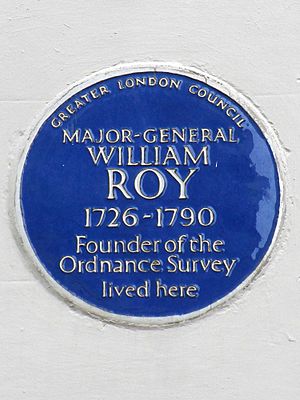

Roy's ideas and leadership led to the creation of the Ordnance Survey in 1791. This is Britain's official map-making organization, and it started the year after he passed away. He won the Copley Medal in 1785 for his amazing work in setting up a special measuring line for surveys. His maps and drawings of Roman ancient sites in Scotland were the first accurate studies of these places. Even today, they are still very useful! Roy was also a member of important scientific groups like the Royal Society.

Contents

About William Roy

His Early Life

William Roy was born on May 4, 1726, in a place called Milton Head, in Carluke, Scotland. His father and grandfather worked as "factors," which meant they managed land and property for wealthy families. Because of this, William grew up seeing maps and land surveys every day.

He went to school in Carluke and then to Lanark Grammar School. We don't know much about what he did right after school. But by the time he was 20, in 1746, he was already working for the Board of Ordnance. This was a government group that dealt with military supplies and engineering. He even made an official map of the Battle of Culloden soon after it happened.

His work caught the eye of Lieutenant-Colonel David Watson, a high-ranking officer in Edinburgh. Roy also did some private mapmaking jobs. He was known as a respected land surveyor even before his military work.

Roy always remembered where he came from. A servant from a local family recalled how Roy would visit. At first, he ate with the servants. But as he became more famous, he would dine with the family, and eventually, he sat in the most important seat at the table!

His Monument

There's a special monument to William Roy where he was born in Carluke. It's a tall pillar, like a trig point used in surveying. The monument says that Miltonhead, his birthplace, stood there. It also mentions that his military map of Scotland, made between 1747 and 1755, led to the creation of the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain.

Roy as a Mapmaker and Soldier

Mapping Scotland

In 1747, after a rebellion in Scotland, Lieutenant-Colonel David Watson suggested making a map of the Scottish Highlands. King George II agreed and asked for a military map of the Highlands. Roy was chosen to start and lead a big part of this project. This map is now known as The Duke of Cumberland's Map.

At first, Roy wasn't a soldier, but Watson made him an assistant. This gave him authority over the small teams of soldiers who worked with him. Each team usually had six people, including chainmen who measured distances.

From 1749, other young mapmakers joined him. Two famous ones were Paul Sandby, who later became known for his beautiful paintings, and a 17-year-old David Dundas, who later became a top commander in the army.

Eventually, six teams were working on the survey. They measured the land by walking in straight lines and sketching what they saw on the sides. The Highlands were mapped by 1752. The survey then continued into the lowlands until 1755. It stopped because a war broke out, and the mapmakers were sent to other military jobs. Roy later said the map was "a magnificent military sketch rather than a very accurate map."

Today, you can see the original maps at the British Museum or view them online.

Military Career

When the Scottish survey ended in 1755, Roy officially joined the military. He became a lieutenant in a new regiment and also a "practitioner-engineer" in the Board of Ordnance.

Roy was promoted quickly in both the army and the engineering department. His army rank was always higher. For example, he became a lieutenant-colonel in the army by 1762. He is best known by his army rank of major-general, which he reached in 1781.

From 1786 until he died in 1790, Roy was the Colonel of the 30th (Cambridgeshire) Regiment of Foot.

Active Service in War

After the Scottish survey, Roy was sent to the south of England in 1756. He helped check military defenses along the coast because a French invasion was expected. He made plans of forts and rough maps of the coastline. These sketches are now kept in the British Library.

By 1757, Roy was fighting in France and then in Germany. He was very good at his job and always found new ways to do things. This made his commanders notice him. Before a battle, engineers usually drew each step of the fight on separate pieces of paper. But Lieutenant Roy drew everything on one sheet with clear, accurate layers. This made it much easier for the commander to understand the battle plan. Roy's method was quickly adopted, and his promotions came fast. By the end of the war in 1763, he was a lieutenant colonel and a director of engineers.

Chief Mapmaker

After the war in 1763, Roy moved to London, where he lived for the rest of his life. He strongly believed that the whole of Britain needed a detailed national map, not just the south coast. He kept pushing for this idea, but wars made it too expensive for about 20 years.

In 1765, he was made "surveyor-general." This meant he had to inspect and report on the coasts of Britain and its islands. This job took him to many parts of Britain and even to Ireland and Gibraltar. His plans and maps from this time are also in the British Library.

Even with all his travels, Roy was active in London's scientific community. In 1767, he became a member of the Royal Society. He gave a talk there in 1783 about how to measure heights using a barometer. He continued to be promoted, becoming a major-general in 1781. By 1783, he was the director of the Royal Engineers.

The Anglo-French Survey

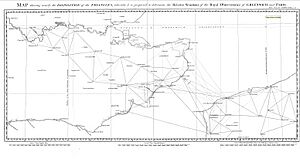

Late in his life, when he was 57, Roy got the chance to make his biggest mark in mapmaking. A French scientist, Cassini de Thury, suggested that the British and French observatories should be precisely linked by a survey.

Sir Joseph Banks, the head of the Royal Society, asked Roy to lead this project. Roy was thrilled! He saw it as the first step toward the national map of Britain he had always wanted. Roy wrote about this project in three major articles for the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

Roy and his team found a good place for their starting measurement line, called a "baseline," on Hounslow Heath near London. It was about 5 miles long. They first measured it with a steel chain. Then, they used special glass tubes, each 20 feet long, for a super accurate measurement. The final measurement of the baseline was 27,404.7 feet, which is about 5 miles. This measurement was incredibly precise, accurate to about 3 inches over 5 miles! Because of this amazing accuracy, Roy received the Copley Medal in 1785.

The main part of the survey, called triangulation, started in 1787. They used a new, super accurate tool called a theodolite. This tool could measure angles with incredible precision, even detecting the Earth's curve! Many measurements, especially across the English Channel, were taken at night using bright flares. Sometimes, they had to place their instruments on church towers or even build tall portable towers.

Roy's final report in 1790 gave the exact distance between Paris and Greenwich, and the precise location and height of the British survey points. Roy also took every chance to mark the positions of many landmarks. These became the basis for new maps. Roy died when he was just a few pages away from finishing his final report.

Roy's Impact on Science

William Roy's use of new scientific ideas and accurate math changed how maps were made. His work marks the point where old, less accurate maps in Britain became new, highly precise ones. He is often mentioned in old math books for his use of "spherical trigonometry" in mapmaking.

Later technical books on modern surveying also point to Roy's work as the beginning of the modern mapmaking profession. Perhaps his greatest legacy is the Ordnance Survey. It started in 1791, a year after he died, by continuing his Anglo-French Survey across the rest of Great Britain over the next sixty years.

Roy as a Historian

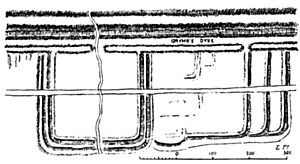

During his survey of Scotland, Roy carefully noted where he found ancient Roman remains, especially military camps. He marked them precisely on his maps. This started his lifelong interest in ancient Scottish history. He continued this interest whenever he traveled as Surveyor General.

Roy's maps and drawings of Roman sites in Scotland were immediately seen as very important and reliable. For places where Roman remains were later destroyed, his drawings are often the only record we have of them.

Roy was the first person to systematically map the Antonine Wall and provide accurate, detailed drawings of what was left of it. He did this in 1764.

Roy's only history book, Military Antiquities of the Romans in Britain, was published after he died in 1793. This book has a mixed reputation. His drawings and maps are highly valued even today. However, his historical discussions are not considered accurate. This is mainly because he believed a fake historical text, De Situ Britanniae, was real. Almost everyone at the time believed it was real too. Because Roy based his ideas on this fake text, his own conclusions were not correct. He spent a lot of time trying to follow made-up journeys described in De Situ Britanniae.

It's a bit sad that some of Roy's great talents were wasted. He was a Scot who loved ancient Scottish history, and his technical skills and scientific knowledge made him uniquely qualified to provide information about a time in history that we know little about. Scottish historians have often regretted this loss for Scottish history.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |