Pyrenean ibex facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pyrenean ibex |

|

|---|---|

|

|

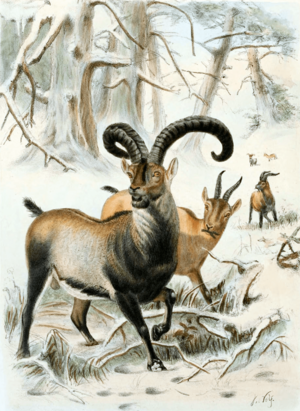

| Illustration from 1898 | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Caprinae |

| Genus: | Capra |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: |

†C. p. pyrenaica

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica (Schinz, 1838)

|

|

The Pyrenean ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) was a type of wild goat. It was one of four subspecies of the Iberian ibex. This animal lived only in the Pyrenees mountains. People called it bucardo in Spanish and Aragonese. In Basque, it was bukardo, and in French, bouquetin.

Pyrenean ibex were often found in the Cantabrian Mountains. They also lived in Southern France and the northern Pyrenees. These ibex were common long ago, during the Holocene and Pleistocene periods. Their skulls were larger than other Capra (goat) types from that time.

Sadly, the last Pyrenean ibex died in January 2000. This meant the subspecies became extinct. Other types of Iberian ibex still exist today. These include the Western Spanish ibex and the Southeastern Spanish ibex. Another subspecies, the Portuguese ibex, had already died out earlier.

Scientists did not get to study the Pyrenean ibex much before it disappeared. Because of this, its exact family tree is still debated. There were attempts to bring the Pyrenean ibex back using cloning. In July 2003, a cloned ibex was born alive. But it only lived for a few minutes because of a lung problem.

Contents

The Pyrenean Ibex Story

Scientists have different ideas about how the Pyrenean ibex came to live in the Iberian Peninsula. They also wonder how the different ibex subspecies are related.

One idea is that the Pyrenean ibex came from an ancestor like the Capra caucasica. This ancestor lived in the Middle East. This might have happened at the start of the last glacial period, about 120,000 to 80,000 years ago. The Pyrenean ibex likely moved from the northern Alps through France. It then reached the Pyrenees around 18,000 years ago.

If this is true, the Pyrenean ibex might have been very different from other ibex types. These other ibex lived in the Iberian Peninsula. This would mean they came from different ancestors. Their genes would also be quite different. We know all four subspecies lived together long ago. But scientists are not sure how much they mixed their genes.

Another idea is that the Pyrenean ibex was already in the Iberian Peninsula. This was before other ibex started moving through the Alps. Genetic studies support the idea that many Capra subspecies came to the Iberian region at the same time. It's possible they even bred together, but we don't have clear proof.

Appearance and Habits

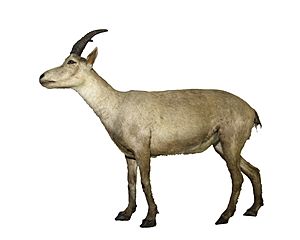

The Pyrenean ibex had short hair. Its fur color changed with the seasons. In summer, its hair was short. In winter, it grew longer and thicker to keep warm. The hair on its neck stayed long all year.

Male and female ibex looked different. You could tell them apart by their color, fur, and horns. In summer, males were a faded grayish-brown. They had black areas on their mane, front legs, and forehead. In winter, their colors were duller. The grayish-brown turned to dull gray, and the black spots faded.

Female ibex looked more like deer. Their coats were brown all summer. Unlike males, females did not have black markings. Young ibex looked like females for their first year of life.

Male ibex had large, thick horns. These horns curved outwards and backwards. Then they curved outwards and downwards, and finally inwards and upwards. The surface of the horn had ridges. These ridges grew more defined with age. Each ridge was thought to represent one year of the ibex's life. So, you could tell its age by counting the ridges. Female ibex had short, cylinder-shaped horns. Ibex ate plants like grasses and herbs.

Life Cycle and Movement

Pyrenean ibex moved to different areas depending on the season. In spring, they would go to higher parts of the mountains. This is where males and females would mate. In spring, females usually separated from the males. They did this to give birth in more private places. Baby ibex, called kids, were usually born in May. Females typically had one kid at a time.

During the winter, the ibex would move to valleys. These valleys were not covered in snow. This allowed them to find food even when the seasons changed.

Where They Lived

The Pyrenean ibex was seen in parts of France, Portugal, Spain, and Andorra. It was less common in the northern parts of the Iberian Peninsula. In places like Andorra and mainland France, the Pyrenean ibex died out first. This happened in the northern tip of the Iberian Peninsula.

At its peak, there might have been 50,000 Pyrenean ibex. They lived in over 50 smaller groups. These groups ranged from the Sierra Nevada to Sierra Morena. Many of these groups lived in mountains in Spain and Portugal. The last Pyrenean ibex were found in the Middle and Eastern Pyrenees. They lived below 1,200 meters (about 3,900 feet) in altitude. However, in southern France, ibex were found at different heights. They lived from 350 to 925 meters (about 1,100 to 3,000 feet) and up to 1,190 to 2,240 meters (about 3,900 to 7,300 feet).

The Pyrenean ibex was very common until the 1300s. Their numbers did not drop much until the mid-1800s. They liked rocky places with cliffs and trees. They also lived in areas with scrub or pine trees. Small rocky patches in farmland or along the coast were also good homes for them. The ibex could live well as long as they had the right habitat. They could also spread out and settle new areas quickly.

Pyrenean ibex were a useful resource for humans. This might have led to their extinction. Researchers think that constant hunting played a role. Also, the ibex might not have been able to compete with other farm animals for food. However, the exact reasons for their extinction are still not fully known.

This subspecies once lived across the Pyrenees in France and Spain. This included the Basque Country, Navarre, northern Aragon, and northern Catalonia. A few hundred years ago, there were many of them. But by 1900, fewer than 100 were left. From 1910 onwards, their numbers never went above 40. They were only found in a small part of Ordesa y Monte Perdido National Park in Huesca, Spain.

Why They Disappeared

The Pyrenean ibex was one of four types of Iberian ibex. The first to become extinct was the Portuguese ibex in 1892. The Pyrenean ibex was the second. The last one, a female named Celia, was found dead in 2000.

In the Middle Ages, there were many Pyrenean ibex in the Pyrenees. But their numbers quickly dropped in the 1800s and 1900s. This was mainly because of too much hunting. By the late 1900s, only a small group lived in the Ordesa y Monte Perdido National Park in Spain.

Competition with farm animals and other wild animals also helped cause their extinction. Much of their land was shared with sheep, goats, cows, and horses. This was especially true in summer when they were in high mountain pastures. This led to animals competing for food. It also caused overgrazing, which hurt the ibex during dry years.

Also, new wild animals were brought into areas where the ibex lived. Examples include fallow deer and mouflon. This increased the pressure on food. It also raised the risk of diseases spreading.

The very last natural Pyrenean ibex, Celia, was found dead on January 6, 2000. She had been killed by a fallen tree. The exact reason for the subspecies' decline is not fully understood. Some ideas include not being able to compete for food, diseases, and illegal hunting.

The Pyrenean ibex became the first animal to be "unextinct" on July 30, 2003. A cloned female ibex was born alive. But she died a few minutes later because of lung problems.

The Cloning Project

Celia, the last ibex, was caught in Ordesa y Monte Perdido National Park. Scientists took small skin samples from her ear. These samples were frozen in nitrogen. Celia died a year after her tissue was collected. In 2000, a company called Advanced Cell Technology, Inc. announced that Spain would let them try to clone her. They planned to use a method called nuclear transfer.

Cloning a goat was expected to be easier than cloning other animals. This is because scientists know more about how goats reproduce. Their pregnancy lasts only five months. Also, only certain extinct animals can be cloned. This is because you need a suitable animal to carry the clone. The company agreed to return any cloned Pyrenean ibex to their original home.

Celia's tissue samples were good for cloning. However, cloning attempts showed a big problem. Even if a healthy female Pyrenean ibex could be made, there were no males to breed with her. To bring back a species, you need genetic samples from many animals. This creates different genes in the cloned group. This is a major challenge for bringing back extinct species through cloning.

One idea was to breed Celia's clones with males from another ibex subspecies. But the babies would not be pure Pyrenean ibex. A more complex plan would be to change a female clone's genes to make a male. But this technology does not exist yet.

Three teams of scientists worked on the cloning project. Two were Spanish, and one was French. Dr. Jose Folch led one of the Spanish teams. Other researchers were from the National Research Institute of Agriculture and Food in Madrid.

The project was managed by the Food and Agricultural Investigation Service of Aragon. The National Institute of Investigation and Food and Agrarian Technology also helped. The National Institute of Agrarian Investigation in France was also involved.

Researchers took adult cells from Celia's tissue. They put these cells into goat eggs that had their own DNA removed. This was to make sure the clone only had Celia's DNA. The new embryos were then put into a domestic goat. This goat acted as a surrogate mother.

The first cloning tries did not work. Out of 285 embryos, 54 were put into 12 ibex or ibex-goat hybrid mothers. Only two survived the first two months of pregnancy, but then they also died.

On July 30, 2003, one clone was born alive. But it died a few minutes later. It had physical problems with its lungs. Despite this, scientists are still studying Celia's frozen cells. They hope to create hybrids. The cells are still alive and frozen. This gives them an advantage over trying to bring back animals like mammoths, whose DNA is very old. Still, cloning technology needs to improve a lot before whole groups of animals can be brought back.

This was the first time scientists tried to bring back an extinct subspecies. The process actually started before the subspecies officially died out.

See also

In Spanish: Bucardo para niños

In Spanish: Bucardo para niños

- De-extinction

- List of resurrected species

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |