Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1499–1501) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1499–1501) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Kingdom of Granada in Castile |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 80,000 | Unknown | ||||||

The First Rebellion of the Alpujarras (Arabic: ثورة البشرات الأولى) happened between 1499 and 1501. It was a series of uprisings by the Muslim people living in the Kingdom of Granada. This area was part of the Crown of Castile and used to be the Emirate of Granada.

The rebellion started in 1499 in the city of Granada. It happened because many Muslims were being forced to change their religion to Catholicism. People felt this broke the 1491 Treaty of Granada. The uprising in the city quickly ended.

However, more serious revolts then began in the nearby mountains called the Alpujarras. The Catholic forces, sometimes led by King Ferdinand himself, stopped these revolts. They punished the Muslim population severely.

The Catholic rulers used these revolts as a reason to ignore the Treaty of Granada. They took away the rights of Muslims that the treaty had promised. All Muslims in Granada were then told they had to become Catholic or leave. By 1502, this rule applied to all Muslims in Castile.

Contents

Why the Rebellion Started

Muslims had lived in Spain for a long time, since the 700s. By the late 1400s, the Emirate of Granada was the last area in Spain ruled by Muslims. In January 1492, after a ten-year war, Muhammad XII of Granada (also called "Boabdil") gave up the Emirate. He surrendered to the Catholic forces led by the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile.

The Treaty of Granada was signed in November 1491. It promised many rights to the Muslims of Granada if they surrendered. These rights included being able to practice their religion and fair treatment.

At that time, about 250,000 to 300,000 Muslims lived in the former Emirate of Granada. They made up most of the people there. They were also about half of all the Muslims in Spain.

At first, the Catholic rulers kept their promises from the treaty. Even though some Spanish church leaders wanted them to be stricter, Ferdinand and the Archbishop of Granada Hernando de Talavera allowed Muslims to practice their faith. They hoped that by living near Catholics, Muslims would choose to become Catholic on their own. When Ferdinand and Isabella visited Granada in 1499, Muslims welcomed them warmly.

In the summer of 1499, Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, a powerful archbishop, came to Granada. He started working with Talavera. Cisneros did not like Talavera's gentle approach. He began sending Muslims who did not cooperate, especially important noblemen, to prison. They were treated harshly until they agreed to convert.

Cisneros became more determined as more people converted. In December 1499, he told Pope Alexander VI that three thousand Muslims had converted in just one day. Even Cisneros's own church council warned that his methods might be breaking the Treaty. Some historians from that time also said his methods "were not correct."

Uprising in Granada City

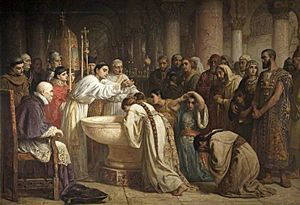

The increasing number of forced conversions made Muslims angry. The first resistance happened in the Albayzín, the Muslim area of Granada city. The situation got worse because of how elches were treated. Elches were Christians who had converted to Islam.

The Treaty of Granada said that elches could not be forced back to Christianity. But it allowed Christian priests to question them if Muslim religious leaders were present. Cisneros used this rule to call elches for questioning. He then imprisoned those who refused to become Christian again. He often focused on the wives of Muslim men. This made the Muslim people very angry, as they felt their families were being attacked.

On December 18, 1499, a police officer named Velasco de Barrionuevo was taking a female elche from the Albayzín for questioning. As they walked through a square, she shouted that she was being forced to become Christian. A crowd gathered around them. The officer was killed, and his helper escaped after a local Muslim woman helped him hide.

This event led to an open revolt. People in the Albayzín blocked the streets and armed themselves. An angry crowd marched towards Cisneros's house, planning to attack. The crowd later broke up, but over the next few days, the revolt became more organized. The people of the Albayzín chose their own leaders.

The archbishop Hernando de Talavera and the military leader Marquis de Tendilla tried to calm things down. They used talks and friendly actions. After ten days, the uprising ended. The Muslims gave up their weapons and handed over the people who killed the officer. These killers were quickly executed.

After this, Cisneros was called to the court in Seville. King Ferdinand was very angry with him. But Cisneros argued that the Muslims, not him, had broken the Treaty by rebelling. He convinced Ferdinand and Isabella to forgive the rebels. But this pardon came with a condition: they had to convert to Christianity. Cisneros then returned to Granada. The city was now officially Christian.

Uprising in the Alpujarra Mountains

Even though the uprising in Granada city seemed over, the rebellion spread to the countryside. The leaders of the Albayzín uprising escaped to the Alpujarra mountains. The people in these mountains were almost all Muslims. They had only accepted Christian rule unwillingly.

They quickly rebelled because they felt the Treaty of Granada had been broken. They also feared they would be forced to convert, just like the people in Granada city. By February 1500, 80,000 Christian soldiers were sent to stop the rebellion. By March, King Ferdinand arrived to lead the soldiers himself.

The rebels often fought well and used the mountains for guerrilla warfare. But they did not have one main leader or a clear plan. This was partly because the Castilian rulers had encouraged rich Granadan Muslims to leave the country or convert and join the Christian upper class. Because the rebels lacked a strong command, the Christian forces could defeat them one area at a time.

The rebelling towns and villages in the Alpujarra were slowly defeated. King Ferdinand personally led the attack on Lanjarón. Rebels who surrendered usually had to be baptized to save their lives. Towns that had to be taken by force were treated very harshly.

One very sad event happened in Laujar de Andarax. Catholic forces captured 3,000 Muslims and then killed many of them. Between 200 and 600 women and children hid in a mosque. The soldiers then blew up the mosque with gunpowder. When Velefique was captured, all the men were killed and the women were made slaves. At Nijar and Güéjar Sierra, everyone was enslaved except for children. These children were taken away to be raised as Christians.

On January 14, 1501, Ferdinand ordered his army to stop fighting. The uprising seemed to be over. However, more unrest happened in Sierra Bermeja. An army led by Alonso de Aguilar, a famous Spanish captain, marched to stop this new rebellion. On March 16, the army's soldiers, eager for loot, charged the rebels without waiting for orders. But the rebels fought back fiercely. This was a disaster for the Catholic army. Aguilar himself was killed, and the army suffered heavy losses.

However, the Muslims soon asked for peace. Ferdinand knew his army was tired and fighting in the mountains was hard. He said the rebels had to choose between leaving Spain or being baptized. Only those who could pay ten gold coins could leave. Most could not pay, so they had to stay and be baptized.

The rebels surrendered in groups, starting in mid-April. Some waited to see if the first groups were safe. Those who left were escorted to the port of Estepona. From there, they sailed to North Africa. The remaining people were allowed to go home after converting, giving up their weapons, and losing their property.

What Happened Next

By the end of 1501, the rebellion was completely stopped. Muslims no longer had the rights promised by the Treaty of Granada. They were given a choice:

- Stay and become Christian.

- Refuse to become Christian and be enslaved or killed.

- Leave the country.

Leaving Spain was very expensive. So, becoming Christian was the only real choice for most of them. Just ten years after the fall of the Emirate of Granada, all Muslims in Granada had officially become Christian.

In 1502, these forced conversions were extended to all other lands of Castile. This happened even though Muslims outside Granada had not been part of the rebellion. The newly converted Muslims were called nuevos cristianos ("new Christians") or moriscos.

Even though they became Christian, they kept many of their old customs. This included their language, names, food, clothes, and some ceremonies. Many secretly practiced Islam while publicly acting as Christians. In response, the Catholic rulers made stricter rules to try and get rid of these customs.

This led to Philip II's Pragmatica law on January 1, 1567. This law ordered the Moriscos to give up their customs, clothing, and language. The pragmatica caused the Morisco revolts between 1568 and 1571.

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión de las Alpujarras (1499-1501) para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión de las Alpujarras (1499-1501) para niños