Resistance in the German-occupied Channel Islands facts for kids

During the German occupation of the Channel Islands in World War II, people living there showed resistance in different ways. There were many German soldiers on the islands compared to the number of civilians – about one soldier for every two or three islanders. This, along with strict punishments from the Germans, meant that most resistance was not violent. Even so, more than twenty civilians died because they resisted the occupiers.

Contents

How the Occupation Began

When Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, some Channel Islanders left to join the armed forces or work in war factories in Britain.

On May 10, 1940, Nazi Germany invaded France and nearby countries. Their fast "Blitzkrieg" (Lightning War) tactics surprised everyone. By June 16, it was clear Germany would win the Battle of France. Islanders worried about staying, but authorities told them to remain to avoid panic.

On June 15, the British government decided to remove its soldiers from the islands, leaving them undefended. Germany didn't know this. On June 28, German planes bombed and attacked the harbours of Saint Peter Port and Saint Helier. This killed 38 civilians and injured 45.

Boats for civilians to evacuate only became available on June 20. People were still told to stay, and only women and children were first allowed to leave. When the island leaders finally left, more people could evacuate. The last official ships sailed on June 23.

In total, about 17,000 people from Guernsey, 6,600 from Jersey, and all 1,400 from Alderney went to England. This large evacuation meant fewer people were left on the islands to resist when the Germans arrived on June 30, 1940.

German Soldiers on the Islands

The German military police, called the Feldgendarmerie, worked on both islands. They handled crimes, traffic, and guarded buildings. Another group, the Geheime Feldpolizei (Secret Field Police), looked for sabotage and rebellion.

Many German soldiers were stationed on the islands. By October 1944, there were 12,000 soldiers in Jersey and 13,000 in Guernsey. Compared to the civilian populations, this meant about one German soldier for every three civilians in Jersey and one for every two in Guernsey. This was a very high number compared to other occupied areas. For example, in France, there was only one German soldier for every 80 civilians.

How Resistance Grew

In July 1940, any military personnel stuck on the islands were sent to prisoner-of-war camps. A year later, all trained army officers, many of whom were retired British people or Islanders who had fought in World War I, were identified. What was left were older veterans and civilians with no weapons or way to contact Britain for help.

Experts say that in other European countries, about 0.6% to 3% of the population actively resisted German occupation. The Channel Islands had a similar percentage. Out of 66,000 islanders, about 4,000 were punished for breaking laws. Many of these were for regular crimes, but some were for resistance. About 570 prisoners were sent to prisons and camps in Europe, and at least 31 people from Jersey and Guernsey did not return.

More than 200 people in Jersey helped forced laborers who had escaped. Over 100 of these people even provided safe houses for them.

How People Organized Resistance

The British government told the island leaders to stay and help the people. Britain also did not encourage or help any resistance on the islands.

Resistance efforts were usually not organized. When they were, they happened through existing social groups. Unlike other countries, the islands didn't have strong political parties or worker groups that could help organize resistance. People focused on surviving rather than on grand acts of defiance.

Some people helped escaped prisoners because they felt it was the right thing to do. Others saw it as the only way to defy the Germans when more active resistance was too difficult. In other occupied countries, people often helped friends or family. In the Channel Islands, those who helped escaped workers were usually sheltering strangers who didn't even speak their language.

Norman Le Brocq led a resistance group called the Jersey Democratic Movement (JDM). This group helped many Soviet forced laborers brought to the island by the Germans. The JDM also spread anti-German messages. They even seemed to have some success in turning German soldiers against their leaders. For example, they may have been involved in setting fire to the Palace Hotel, which led to a nearby ammunition dump exploding.

Escaping the Islands

A total of 225 islanders escaped to England or France: 150 from Jersey and 75 from Guernsey. Many people drowned or were caught while trying to escape.

After D-Day in 1944, more people tried to escape. Conditions on the islands got worse as supplies were cut off. People also wanted to join the fight to free Europe, and the escape route to France became shorter.

In May 1942, three young people, Peter Hassall, Maurice Gould, and Denis Audrain, tried to escape from Jersey in a boat. Audrain drowned, and Hassall and Gould were imprisoned in Germany, where Gould died. After this, the Germans put more rules on small boats.

Some escapees carried important information about German defenses and messages to Britain. Successful escapees were questioned to get as much information as possible about the islands.

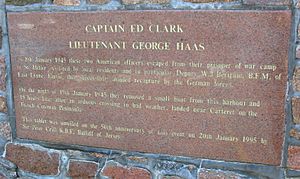

Once the Cherbourg area in France was controlled by the Allies, escaping became "easier." Two American officers, Captain Ed Clark and Lieutenant George Haas, escaped from a prisoner-of-war camp in St. Helier in January 1945. With help from islanders, they crossed to France. Helping them meant a death penalty if caught.

Types of Resistance

Resistance included quiet acts of defiance, small acts of damage, hiding and helping escaped forced workers, and printing secret newspapers with news from BBC Radio. If caught, the punishments could be very harsh.

Resistance began very early. A local newspaper on July 1, 1940, published a German order using its exact spelling, including a mistake, which was a subtle act of defiance.

There were no civilian radio transmitters on the islands, and Britain didn't try to send any. The islands remained cut off from Britain during the occupation.

Quiet Acts of Resistance

Some acts of defiance were very small and personal. This included crossing the street to avoid a German soldier, knocking on a door using the morse code for "V" (•••-), or giving a piece of food to a starving forced worker.

The Guernsey Evening Press and The Star newspapers continued to publish, even with German censorship. Frank Falla, a key member of the Guernsey "Resistance," helped create the Guernsey Underground News Sheet (GUNS). GUNS printed BBC news that was received secretly. Falla was eventually betrayed and sent to Germany, but he survived. Other members of GUNS did not return.

In Jersey, a shortage of coins led to new banknotes being printed. Artist Edmund Blampied designed the 6 pence note so that when folded, the word "six" formed a "V" for victory. A year later, he designed postage stamps. On the 3 pence stamp, he cleverly put the initials "GR" (for King George VI) to show loyalty to the King. Blampied also forged stamps for documents for people trying to escape.

In June 1943, the bodies of two British airmen washed ashore in Jersey. Their military funeral attracted large crowds. In November 1943, after two British Navy ships sank, the bodies of 21 Royal Navy and Royal Marines men washed up in Guernsey. The Germans buried them with full military honors. About 5,000 islanders attended the funeral, laying 900 wreaths. This was such a strong show of defiance that the Germans closed future military funerals to civilians.

Islanders also joined in Churchill's "V for Victory" campaign by painting "V"s over German signs. Germans then painted their own "V" signs. People even made secret "V" badges from coins. Scouting and the Salvation Army were banned but continued secretly.

When radios were taken away, people started making and hiding "crystal sets" to listen to the BBC. They used parts from public phones and even metal bed frames as antennas.

The occupation also led to more people speaking the local languages, Guernésiais and Jèrriais. Since many German soldiers understood English and French, islanders used their local languages to talk without being understood.

Active Resistance

There was no armed resistance movement in the Channel Islands. This was because the British government had removed its military, the islands were small with no hiding places, and there were many German soldiers. Also, many young men had already joined the British or French armed forces.

Small acts of damage, like cutting a telephone wire, could lead to harsh punishments. For example, men in the area might have to stand guard duty for several nights.

Marie Ozanne, a Salvation Army Major, protested against the ban on open-air preaching and the cruel treatment of forced laborers. Her protests led to her imprisonment. She died in April 1943 at age 37. Her courage was an example to others.

Reverend Cohu would secretly share BBC news during his church sermons to cheer up his community. He was arrested in March 1943, sent to a German SS camp, and died in September 1944.

Two French artists, Lucille Cahun and Suzanne Malherbe, created anti-German leaflets using BBC news. They would put these leaflets in soldiers' pockets or on their chairs, encouraging them to turn against their officers. They were caught in 1944 and sentenced to death, but their sentence was changed to prison.

Dr. Noel McKinstry, Jersey's Medical Officer of Health, hid escaped workers in his home. He also provided fake papers and changed statistics to get extra supplies for them. Other officials helped by providing ration cards and identity cards. Some islanders taught the escaped workers English.

Miriam Milbourne risked her life to save a rare breed of Golden Guernsey goats by hiding them for years. A farmer also hid his bull in a haystack for years, only letting it out at night.

The British government did not encourage resistance in the Channel Islands. They believed it wouldn't be effective and could lead to violent revenge against the islanders.

On March 9, 2010, the British government honored 25 people as "British Hero of the Holocaust" for helping victims of the Holocaust. Four Jerseymen were among them: Albert Bedane, Louisa Gould, Ivy Forster, and Harold Le Druillenec. This was the first time Britain recognized the heroism of islanders during the German occupation.

Public Feelings About the Occupation

People's feelings about German rule changed over time. At first, the Germans tried to appear non-threatening. Many islanders were willing to cooperate as long as the Germans acted correctly. Two big events changed this passive attitude: radios being taken away and large groups of people being deported.

Listening to BBC Radio was banned in 1942, and all radios were confiscated. This made islanders very angry, and they secretly continued to listen to the BBC using hidden radios or homemade "crystal sets." German raids looking for radios made people even more resentful.

In 1942, Hitler ordered British civilians in the Channel Islands to be sent to camps in Germany. This was against international law. The Germans on the islands delayed, but Hitler insisted.

The unfairness of these deportations angered those who remained and made them more willing to support resistance activities. The deportees sang patriotic songs as they left, like "There'll Always Be an England".

More anger came from a second deportation in early 1943, after a British commando raid on Sark resulted in German soldiers being killed.

Seeing the brutal treatment of slave workers also showed islanders the true cruelty of the Nazi regime. Forced marches and public beatings made the harshness of the occupation very clear.

After the Normandy invasion in June 1944, things changed. Prisoners could no longer be sent to France, and supplies to the islands were cut off. Both sides knew Germany was losing the war. The island authorities became less obedient and asked for more, like help from the International Committee of the Red Cross. The Germans started agreeing to more of these requests. Even Britain changed its mind about helping the islands, with Churchill initially saying, "Let them starve."

The Channel Islands were bypassed during the Battle of Normandy, leading to widespread hunger in the winter of 1944–1945. Each arrival of the Red Cross ship Vega brought brief moments of celebration. In April 1945, British flags started appearing, and people were warned not to anger the Germans. The true feelings of the islanders burst out on May 9, 1945, when they were finally freed.

The islands' occupation was a difficult topic for Churchill, as his "We will fight them on the beaches" speech didn't apply to the Channel Islands, which Britain had left undefended.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth made a special visit to the islands on June 7, 1945.

Punishments for Resistance

On December 13, 1940, sixteen young French soldiers tried to sail from France to England to join the Free French forces. They landed in Guernsey by mistake and were captured by German guards. Six were sent to Jersey for trial. François Scornet was named the leader and sentenced to death. He was shot by a firing squad on March 17, 1941.

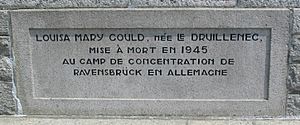

Louisa Gould hid a wireless set and sheltered an escaped Soviet prisoner. Betrayed by an informer at the end of 1943, she was arrested and sentenced on 22 June 1944. In August 1944 she was transported to Ravensbrück where she died on 13 February 1945. In 2010 she was posthumously awarded the honour British Hero of the Holocaust.

Anyone caught for resistance faced prison. Some were sent off the island. For listening to the BBC, a common punishment was four weeks in a local prison, then deportation to a prison in France, and finally to Germany as a forced laborer for years. This was mild compared to the SS "Nacht und Nebel" (Night and Fog) order from December 1941, which said that even a life sentence was "weak" and recommended death or disappearance for anyone resisting.

In July 1941, Colonel Knackfuss warned that anyone caught spying, sabotaging, or committing high treason would face death. Even worse, if communication lines were attacked, the Germans could pick anyone in the area and sentence them to death.

Ambrose Sherwill, a leader in Guernsey, was sent to prison in Paris for helping two British soldiers. He managed to get them treated as prisoners of war instead of spies, saving their lives.

Harold Le Druillenec, brother of Louisa May Gould, was arrested on June 5, 1944, for helping an escaped Russian prisoner of war and having a radio. He was sent to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp for ten months and was the only British survivor from that camp. He described the terrible conditions, including having to move dead bodies and cannibalism among prisoners.

A number of Islanders died because of their resistance activities, including:

Jersey

- Clifford Cohu: a clergyman, arrested for speaking out against the Germans. Died in Spergau.

- Arthur Dimmery: punished for digging up a hidden radio. Died in Laufen.

- Maurice Jay Gould: arrested after trying to escape to England. Died in Wittlich.

- Louisa Gould: arrested for hiding an escaped slave worker. Died in Ravensbrück concentration camp.

- James Edward Houillebecq: sent away after stolen gun parts were found. Died in Neuengamme concentration camp.

- Frank René Le Villio: sent away for stealing a motorbike. Died in a hospital in Nottingham after the war.

- William Howard Marsh: arrested for spreading BBC news. Died in Naumburg prison.

- Edward Peter Muels: arrested for helping a German soldier escape after killing his officer.

- John Whitley Nicolle: a leader in a secret radio network. Died in Dortmund.

- Léonce L'Hermitte Ogier: a lawyer, arrested for having maps of defenses and a camera. Died in prison.

- Frederick William Page: punished for not giving up his radio. Died in Naumburg-am-Saale prison.

- Clarence Claude Painter: arrested when a radio and photos of military sites were found. Died on a train to Mittelbau-Dora.

- Peter Painter: son of Clarence Painter, arrested when a pistol was found in his closet. Died in Natzweiler-Struthof.

- June Sinclair: a hotel worker, punished for slapping a German soldier. Died in Ravensbrück concentration camp.

- John (Jack) Soyer: punished for having a radio, escaped prison in France, and died fighting with a French resistance group.

- Joseph Tierney: the first person arrested from a secret radio network. Died in Celle.

Guernsey

- Sidney Ashcroft: found guilty of theft and resisting officials in 1942. Died in Naumburg prison.

- Joseph Gillingham: involved in the Guernsey Underground News Service (GUNS). Died in Naumburg prison.

- John Ingrouille: aged 15, found guilty of treason and spying, sentenced to five years hard labor. Died in Brussels after being released in 1945.

- Charles Machon: the creator of GUNS. Died in Hamelin prison.

- Percy Miller: sentenced to 15 months for radio offenses. Died in Frankfurt prison.

- Marie Ozanne: refused to accept the ban on the Salvation Army. Died in Guernsey hospital after leaving prison.

- Louis Symes: hid his son, who was on a commando mission to the island. Died in Cherche-Midi prison.

Images for kids

-

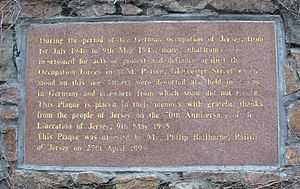

Plaque: "During the period of the German occupation of Jersey, from 1 July 1940 to 9 May 1945, many inhabitants were imprisoned for acts of protest and defiance against the Occupation Forces in H.M. Prison, Gloucester Street which stood on this site. Others were deported and held in camps in Germany and elsewhere from which some did not return."

-

During the German occupation of Jersey, a stonemason repairing the paving of the Royal Square incorporated a V for victory under the noses of the occupiers. This was later amended to refer to the Red Cross ship Vega. The addition of the date 1945 and a more recent frame has transformed it into a monument.

-

Plaque on war memorial, Saint Ouen, Jersey, to Louisa Mary Gould, victim of Nazi concentration camp Ravensbrück: Louisa Mary Gould, née Le Druillenec, mise à mort en 1945 au camp de concentration de Ravensbrück en Allemagne.

Louisa Gould hid a wireless set and sheltered an escaped Soviet prisoner. Betrayed by an informer at the end of 1943, she was arrested and sentenced on 22 June 1944. In August 1944 she was transported to Ravensbrück where she died on 13 February 1945. In 2010 she was posthumously awarded the honour British Hero of the Holocaust.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |