Jèrriais facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Jèrriais |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| jèrriais | ||||

| Native to | Jersey and Sark | |||

| Native speakers | 1,900 (2011 census)e18 2,800 L2 speakers of Jersey and Guernsey |

|||

| Language family | ||||

| Early forms: |

Old Latin

|

|||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | Jersey | |||

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-hc | |||

|

||||

|

||||

Jèrriais is a special language and the traditional way people in Jersey have spoken for a long time. It's a type of Norman language used on the island of Jersey, which is part of the Channel Islands. These islands are located off the coast of France.

Jèrriais is closely related to other Norman languages, like Guernésiais, which is spoken on the nearby island of Guernsey. It's also related to other langues d'oïl, which are languages from northern France.

Over the last 100 years, fewer and fewer people have been speaking Jèrriais. This is because English became the main language for schools, businesses, and government in Jersey. There are now very few people who learned Jèrriais as their first language. Their numbers are getting smaller each year because the speakers are mostly older. But don't worry, people are working hard to keep the language alive!

The language spoken on the island of Sark, called Sercquiais, actually came from Jèrriais. Jersey colonists settled Sark in the 1500s and brought their language with them. People who speak Sercquiais can often understand the Norman language spoken in mainland Normandy.

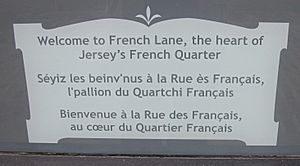

Sometimes, Jèrriais is called "Jersey French" or "Jersey Norman French" in English. However, this can be a bit confusing because it's not the same as the French used for legal documents in Jersey, which is called Jersey Legal French. To avoid confusion, some people prefer to call it "Jersey Norman."

Contents

History of Jèrriais

Even though few people speak Jèrriais as their main language today, it was the everyday language for most people in Jersey until the 1800s. Before the Second World War, about half of the island's population could still speak it.

People started to notice the language was declining in the 1800s. Famous people like Victor Hugo, who lived in Jersey for a while, were interested in Jèrriais. He even knew some Jèrriais writers.

Writers in Jersey and nearby Guernsey helped create a standard way to write Jèrriais. This was based on French spelling rules. However, Jersey, Guernsey, and mainland Normandy still use slightly different writing systems for their Norman languages.

As English became more common in Jersey during the 1900s, people started working to save Jèrriais.

- The Jersey Eisteddfod, a local festival, has had a Jèrriais section since 1912.

- Groups like L'Assembliée d'Jèrriais (started in 1951) and Le Don Balleine (a trust set up by Arthur E. Balleine) were created to promote the language.

- A Jèrriais magazine started in 1952.

- A grammar book, Lé Jèrriais pour tous, was published in 1985.

- Cassettes and other learning materials were also made.

Many Jersey people moved to North America long ago, especially to work in the cod fishing industry in Quebec, Canada. Jèrriais was often used for business there. Some people even reported hearing Jèrriais speakers in Canadian villages in the 1960s!

During the German Occupation of the Channel Islands in the Second World War, local people used Jèrriais to talk to each other. The German soldiers and their French interpreters couldn't understand it, which was very useful! However, after the war, English became even more common.

It's thought that the last adults who only spoke Jèrriais probably passed away in the 1950s. But some children who only spoke Jèrriais were still starting school in the late 1970s.

Did you know that famous people like Lillie Langtry and the painter Sir John Everett Millais reportedly spoke Jèrriais to each other?

Jèrriais Dictionaries

People have been creating Jèrriais dictionaries since the 1800s.

- The Glossaire du Patois Jersiais was published in 1924.

- The Dictionnaire Jersiais–Français (Jèrriais-French dictionary) came out in 1966.

- The first English-Jèrriais dictionary was published in 1972.

- A children's picture dictionary, Les Preunmié Mille Mots (The First Thousand Words), was released in 2000.

- Newer dictionaries, like the Dictionnaithe Jèrriais-Angliais (Jèrriais-English) in 2005 and Dictionnaithe Angliais-Jèrriais (English-Jèrriais) in 2008, have also been published.

Current Status of Jèrriais

Recent surveys show how many people speak Jèrriais today.

- A 2012 survey found that 18% of people in Jersey could speak some Jèrriais words or phrases.

- More than 7% of people over 65 were fluent or could speak a lot of Jèrriais.

- About 5% of adults could usually or fully understand someone speaking Jèrriais.

- Only a small number (under 1%) could write Jèrriais fluently.

These numbers are from the 2001 census. That census showed about 3% of the island's population spoke Jèrriais regularly. However, other research suggests up to 15% of people understand some of the language. The latest census also showed more children speaking Jèrriais, which is great news! This is likely thanks to Jèrriais teaching programs in Jersey schools.

The parish (like a county) with the most Jèrriais speakers is Saint Ouen. The parish with the fewest is Saint Helier, even though it's the largest.

The government of Jersey, called the States of Jersey, helps fund Jèrriais teaching in schools. They also support signs in Jèrriais at places like the airport. They are even discussing officially recognizing Jèrriais under a European agreement for minority languages.

In 2005, the States of Jersey decided to work on a plan to help the language. They said:

Jersey almost lost its language in the 20th century. Now, big efforts are being made to bring it back. Le Don Balleine is leading a program to teach Jèrriais in schools. L'Assembliée d'Jèrriais promotes the language in general. Language helps make a place special and gives people a sense of belonging. It's really important for Jersey's identity. This plan is to help these groups revive and improve the language's standing.

In 2009, a special agreement was signed to make L'Office du Jèrriais responsible for protecting and promoting Jèrriais. They also created a plan to make the language more visible every day. You can find Jèrriais in newspapers and on the radio. Since 2010, Jersey banknotes even have the value written in Jèrriais!

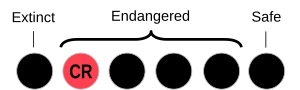

The Endangered Languages Project currently lists Jèrriais as "threatened." However, the British and Irish governments recognize Jèrriais as a regional language. In 2019, the States of Jersey officially made Jèrriais an official language. This means it will be used on signs and official letters.

Jèrriais Literature

The history of writing in Jèrriais goes way back to Wace, a poet from Jersey in the 1100s. But most of the Jèrriais literature we have today was written after the first printing press arrived in Jersey in the 1780s.

The first printed Jèrriais appeared in newspapers in the late 1700s. Newspapers and journals in the 1800s were a great place for poets and writers to share their work. They often wrote funny comments about the news or local politicians. The first collection of Jèrriais poems, Rimes Jersiaises, was published in 1865.

Important writers include "Laelius" (Sir Robert Pipon Marett) and "A.A.L.G." (Augustus Aspley Le Gros). "Elie" (Edwin J. Luce) was a newspaper editor and poet. He also helped start Jèrriais plays and performances, which led to the Jèrriais section of the Jersey Eisteddfod in 1912.

During the German occupation of the Channel Islands in World War II, the German censors didn't allow much new writing. So, older Jèrriais stories and poems were reprinted in newspapers to boost morale. After the war, Edward Le Brocq started a weekly newspaper column with letters from a fictional old couple, "Ph'lip et Merrienne", who talked about the news and old times.

One of the most important Jèrriais writers in the 1900s was George F. Le Feuvre (who used the pen-name "George d'la Forge"). He moved to North America after World War I. But for almost 40 years, he kept sending articles in Jèrriais back to Jersey newspapers. His articles have been published in books.

Frank Le Maistre, who created the Dictionnaire Jersiais–Français, also wrote a lot. He wrote newspaper articles, poems, and did research on place names. More recently, Geraint Jennings has helped save the language by putting thousands of pages of Jèrriais text online in Les Pages Jèrriaises, including parts of the Bible.

Jèrriais Vocabulary

Jèrriais is a Romance language, which means it comes from Latin. But it also has some words from Old Norse. This happened when Norse-speaking Normans (who were "North-men") took over the area now called Normandy. They started speaking the local language, but their own language influenced it. So, Jèrriais has some Norse words, plus words borrowed from other languages later on.

Words from Norse

Here are some Jèrriais words that come from Old Norse:

- mielle (meaning sand dune)

- mogue (meaning mug)

- bel (meaning yard)

- gradile (meaning blackcurrant)

- mauve (meaning seagull)

- graie (meaning to prepare)

- hèrnais (meaning cart)

- bète (meaning bait)

- haûter (meaning to doze)

Words from Breton

Jèrriais has also borrowed a few words from the Breton language. For example:

- pihangne (meaning spider crab, from Breton bihan 'small')

- quédaine (meaning fast, from Breton gaden 'hare')

However, most of the influence on Jèrriais today comes from French and, more and more, from English.

Words from French

Many French words have entered Jèrriais. This happened because French was an official language and because of French culture and literature. Some French words have even replaced older Jèrriais words. For example:

- French leçon (lesson) replaced the native Jèrriais word lichon.

- French garçon (boy) replaced the native Jèrriais word hardé.

- French chanson (song) replaced the native Jèrriais word canchon.

People are working to keep some native Jèrriais words, even if French forms are becoming more common. For example:

- They promote hielle over French huile (oil).

- They promote huiptante (eighty) over French quatre-vingts (which means four-twenties).

Words from English

Some words from English entered Jèrriais a long time ago, especially words about the sea. For example, baûsouîn (from boatswain). Later, by the late 1700s, some everyday words also came from English. This happened when Jèrriais-speaking servants worked in English-speaking homes.

- bliatchinner (to polish shoes, from blacking)

- coutchi (to cook)

- grévîn (gravy)

- ouâchinner (to rub in soapy water, from washing)

- scrobbine-broche (scrubbing brush)

- sâsse-paine (saucepan)

- stchilet (skillet)

- ticl'ye (from tea-kettle)

- code à phôner (phone code)

Other words borrowed from English before 1900 include:

- chârer (to share)

- drâses (underpants, from drawers)

- ouothinner (to worry)

- ouadinne (cotton wool, from wadding)

- nosse (nurse)

- souîndgi (to throw, from swing)

- sténer (to stand, to endure)

It's interesting to note that some words, like mogue (mug) and canne (can), might seem like they came from English. But actually, they were Norman words that went to England after the Norman Conquest. Also, words like fliotchet (flock) and ridgi (rig) are Norman words that are similar to English words because they share a common origin.

More recently, words like boutchi (to book), partchi (to park), and tyeur (tyre) have been added to the language. When creating new words for technology, people try to avoid just borrowing from English. For example, they made up textéthie for texting, maître-pêtre for webmaster (which literally means master-spider), and mégabouochi for megabyte.

Jèrriais Grammar

Verbs and Time

Jèrriais has different ways to show when something happened or how it's happening. This is called grammatical aspect.

Here's how Jèrriais shows different times for verbs:

Past Time

| Simple Past | j'pâlînmes | we spoke |

| Happening in Past | ou 'tait à pâler | she was speaking |

| Completed Action | ous avez pâlé | you have spoken |

| Ongoing Past | j'pâlais | I spoke (repeatedly or over time) |

Future Time

| Simple Future | j'pâl'lai | I will speak |

| Happening in Future | tu s'sa à pâler | you will be speaking |

| Completed by Future | oulle étha pâlé | she will have spoken |

Present Time

| Simple Present | j'pâle | I speak |

| Happening Now | i' sont à pâler | they are speaking |

Repeating Actions

You can show that an action is happening again by adding èr- or r' to the beginning of a verb.

| aver | have |

| èraver | have again |

| êt' | be |

| èrêt' | be again |

| netti | clean |

| èrnettit | clean again |

| muchi | hide |

| èrmuchi | hide again |

| èrgarder | watch |

| èrèrgarder | watch again |

| téléphoner | phone |

| èrtéléphoner | phone again |

Verbs as Nouns (Gerunds)

You can change verbs into nouns that describe the action itself. These are called gerunds. They are used a lot in Jèrriais.

| chanter | sing |

| chant'tie | singing |

| faithe | make |

| faîs'sie | making |

| haler | pull |

| hal'lie | hauling, haulage |

| partchi | park |

| parqu'thie | parking |

| liéthe | read |

| liéthie | reading |

| faxer | fax |

| faxéthie | faxing |

Examples of Jèrriais Words

Here are some common words in Jèrriais, along with their French and English meanings:

| Jèrriais | French | English |

| Jèrri | Jersey | Jersey |

| beinv'nu | bienvenue | welcome |

| bel | cour | garden (yard) |

| bieauté | beauté | beauty |

| bouônjour | bonjour | hello |

| brînge | brosse | brush |

| chièr | cher | dear |

| compather | comparer | compare |

| l'êtrangi | l'étranger | abroad |

| janmais | jamais | never |

| lian | lien | link |

| tchaîse | chaise | chair |

| ticl'ye | bouilloire | kettle |

| viages | voyages | journeys |

| yi | œil | eye |

See also

In Spanish: Idioma jerseyés para niños

In Spanish: Idioma jerseyés para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |