Richard Arrington Jr. facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Arrington Jr.

|

|

|---|---|

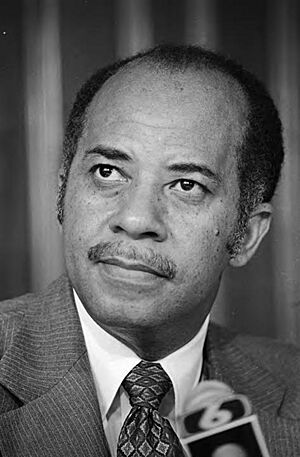

Arrington is at a microphone, possibly for a news conference.

|

|

| 25th Mayor of Birmingham, Alabama | |

| In office November 13, 1979 – 1999 |

|

| Preceded by | David Vann |

| Succeeded by | Bernard Kincaid |

| Member of the Birmingham City Council | |

| In office 1971–1979 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 19, 1934 Livingston, Alabama |

| Spouses | Barbara Jean Watts (1954–1974) Rachel Reynolds (1975–) |

| Children | Anthony, Kevin, Kenneth, Angela, and Erica |

| Residence | Birmingham, Alabama |

| Alma mater | Miles College (BA) University of Detroit (ME) University of Oklahoma (Ph.D) |

| Profession | College Professor |

Richard Arrington Jr. (born October 19, 1934, in Livingston, Alabama) made history as the first African American mayor of Birmingham, Alabama. Before becoming mayor, he served on the Birmingham City Council. He worked hard to improve the city's economy, stop police brutality, and make sure everyone, especially minorities, was treated fairly.

Arrington was mayor for 20 years, from 1979 to 1999. During his time in public service, he faced many challenges, including unfair treatment and investigations. He worked to make Birmingham a city where all people could be proud.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in Alabama

Richard Arrington Jr.'s family moved to Fairfield, Alabama, a steel-producing town, when he was five years old. His father worked for U.S. Steel, which was a better job than sharecropping. To earn more money, his father also worked as a brick mason.

His parents taught him to be independent. They chose to rent their home instead of living in company housing. They also supported a Black-owned store. Richard's mother, Ernestine, made sure the family had home-grown food and that her children used opportunities from church and school.

Church and Community

The Arrington family attended Crumbey Bethel Primitive Baptist Church. Richard was very active there, taking on many leadership roles. As a teenager, he was secretary of the Sunday School. He later became the Sunday School superintendent and a member of the choir. He was also elected to the Board of Deacons, a role he kept even during his political career.

Richard Arrington Jr.'s Education

Richard Arrington Jr. was an excellent student at Fairfield Industrial High School. He graduated in 1951 at age 16. He then attended Miles College in Fairfield, where he studied biology. He was a top student and a leader, becoming president of his fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha. He was also part of the Honor Society and the Thespian Club. He graduated with honors in 1955.

After college, Arrington became a graduate assistant at the University of Detroit in Detroit, Michigan. There, he experienced a community where people of different backgrounds lived together. This helped him see how unfair segregation was in his hometown. He earned his master's degree in 1957.

He returned to Miles College as a science professor. In 1963, he started his doctoral program in Zoology at the University of Oklahoma. This was during the Birmingham Campaign, a time of major civil rights protests in Birmingham. He earned his doctorate in 1966, completing his studies on beetles. He then returned to Miles College, becoming the Dean of the College.

Family Life

Richard Arrington Jr. married his first wife, Barbara Jean Watts, while in college. They had five children: Anthony, Kevin, Kenneth, Angela, and Erica. His family supported him throughout his career. Later, he married Rachel Reynolds, who also supported his vision for a united Birmingham.

City Council Member: 1971-1979

Campaigns and Elections

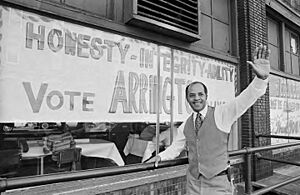

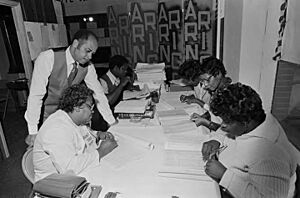

In 1971, Arrington ran for a seat on the Birmingham City Council. He promised to make Birmingham "a city of which all her people can be proud." He won his seat easily, thanks to a large turnout of African American voters. He became the second African American to serve on the council, after Arthur Shores. His second election for City Council was even smoother, as he won without needing a runoff election.

Important Changes and Achievements

As a council member, Arrington worked to promote affirmative action in Birmingham. This meant making sure that city departments hired and worked with companies that included minorities. He helped pass rules that encouraged fair hiring practices.

Arrington also pushed for an investigation into reports of police brutality. One important case involved the death of Willis "Bugs" Chambers Jr. in police custody. Arrington insisted the council investigate, which was a big step for the city. This investigation helped bring more attention to police procedures. Another case involved Bonita Carter, an 18-year-old African American girl killed by a police officer. When the mayor at the time refused to fire the officer, Arrington decided to run for mayor himself. He wanted to end police brutality and bring more positive change to Birmingham.

Mayor of Birmingham: 1979-1999

Winning the Mayoral Elections

Richard Arrington Jr. won the 1979 mayoral election. He had strong support from African American voters, with 73% of them voting in the runoff election. Even though only 10% of white voters supported him, he became Birmingham's first African American mayor.

He won reelection multiple times. In 1983, he won 60% of the votes. In 1987, he won 64% of the vote, even with three opponents. For his fourth term in 1991, he faced a federal investigation, but he still won easily. In 1995, he ran for his fifth and final term. Despite having seven opponents, he won with 54.9% of the vote.

Building a Better Birmingham

As mayor, Richard Arrington Jr. worked to improve Birmingham's economy and buildings. The city still faced high unemployment after the Great Depression. He worked to bring new businesses, like banking and finance companies, to the city. He also helped expand the city's industries beyond just steel.

Under his leadership, the University of Alabama at Birmingham became the city's largest employer. It also provided important medical research and healthcare. Arrington also added nearby areas to the city, which helped increase its land and tax money.

He created programs to improve Birmingham's economy. This included creating groups to help rebuild the city center. He also used government money to turn Five Points South into a modern area. In 1989, he started the Birmingham Plan, which set goals for construction projects in the city.

Changing City Government

During his 20 years as mayor, Arrington also changed how the city government worked. He fought to choose his own staff, and he won. This allowed him to select department heads and staff, many of whom were minorities. This brought more professionalism and diversity to City Hall.

He also helped start the Alabama New South Coalition, a group that worked for social change. In 1992, he appointed the city's first African American chief of police, Johnnie Johnson Jr..

Challenges and Investigations

Richard Arrington Jr. faced many challenges during his time in public service. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) investigated him throughout his political career.

The FBI began their investigation in 1972, shortly after he joined the City Council. At that time, Arrington was speaking out against police brutality and working to help African Americans vote. The FBI believed he was an "extremist."

The investigations continued into the 1980s. The FBI looked into all of Arrington's finances and meetings. He denied any wrongdoing. Even his wife's retail store was investigated. Listening devices were found in City Hall, including on the mayor's phone, but no link to the FBI was ever proven.

In 1989, a real estate developer told Arrington that the FBI and a U.S. Attorney had tried to get him to falsely accuse the mayor of wrongdoing. The goal was to get Arrington to accept a bribe. However, the FBI stopped this plan after other African American politicians refused to take bribes.

In 1990, the FBI and IRS started investigating Arrington again. Many of his records were requested by a federal grand jury. In 1993, a conviction against a city consultant, who the press linked to the mayor, was overturned. Arrington's records showed he had not met with an ex-partner who claimed to have bribed him.

In 1992, Arrington refused to give his personal logs to the investigation. He believed they could be used to create a false story. He was sent to prison for two days for this refusal. However, once the U.S. Attorney in charge of the case stepped down, Arrington gave up his records and cooperated fully. The investigation found no evidence that the mayor had taken bribes or done anything illegal.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |