Roald Hoffmann facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Roald Hoffmann

|

|

|---|---|

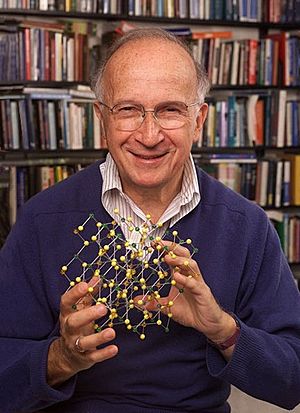

Hoffmann in 2015

|

|

| Born |

Roald Safran

July 18, 1937 Złoczów, Second Polish Republic

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Columbia University Harvard University |

| Known for | Woodward–Hoffmann rules Extended Hückel method Isolobal principle |

| Spouse(s) |

Eva Börjesson

(m. 1960) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical Chemistry |

| Institutions | Cornell University |

| Thesis | Theory of Polyhedral Molecules: Second Quantization and Hypochromism in Helices. (1962) |

| Doctoral advisor |

|

| Doctoral students | Jing Li |

| Other notable students | Jeffrey R. Long (undergraduate), Karen Goldberg (undergraduate) |

Roald Hoffmann, born Roald Safran on July 18, 1937, is a famous Polish-American theoretical chemist. He won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1981. Besides his science work, he also writes plays and poetry. He used to be a professor at Cornell University.

Contents

Early Life and Survival

Roald Hoffmann was born in Złoczów, which was then part of Poland. His family was Polish-Jewish. He was named after the famous explorer Roald Amundsen. His father, Hillel Safran, was an engineer, and his mother, Clara Rosen, was a teacher.

Hiding During World War II

When Germany invaded Poland, Roald's family was forced into a labor camp. His father was a valuable prisoner because he knew a lot about the local area. As the situation became very dangerous, the family managed to escape by bribing guards.

Roald, his mother, two uncles, and an aunt hid for 18 months. They stayed in the attic and a storeroom of a local schoolhouse. This was from January 1943 to June 1944, when Roald was between 5 and 7 years old. A kind Ukrainian neighbor, Mykola Dyuk, helped them hide.

Roald's father stayed at the labor camp. He was later killed by the Germans for trying to help prisoners get weapons. When his mother heard the news, she wrote her feelings in a notebook. While they were in hiding, Roald's mother taught him to read. She also had him memorize geography from textbooks found in the attic. Roald remembers this time as being "enveloped in a cocoon of love."

In 1944, they moved to Kraków, where his mother remarried. They took on her new husband's last name, Hoffmann. Most of their other family members did not survive the war. In 1949, Roald and his family moved to the United States.

In 2006, Roald Hoffmann visited Zolochiv with his son. He found that the attic where he had hidden was still there. The storeroom, however, had become a chemistry classroom. In 2009, Hoffmann helped build a monument in Zolochiv to remember the victims of the Holocaust.

Personal Life and Education

Roald Hoffmann married Eva Börjesson in 1960. They have two children, Hillel Jan and Ingrid Helena. He has said that he is "an atheist who is moved by religion."

School and University

Hoffmann finished high school in New York City in 1955. He won a science scholarship. He then earned his first university degree from Columbia University in 1958. He continued his studies at Harvard University, getting his Master's degree in 1960.

He earned his PhD from Harvard University. He worked with two professors, Martin Gouterman and William N. Lipscomb, Jr.. Lipscomb later won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1976. Hoffmann studied how atoms connect in molecules. He helped create a method called the Extended Hückel method to understand molecular orbitals. In 1965, he started working at Cornell University, where he is now a professor emeritus.

Amazing Scientific Discoveries

Roald Hoffmann's research focuses on how molecules are built and how they react. He has studied many types of molecules, including organic and inorganic ones. He also looked at how metals react and how materials behave in a solid state. He created computer tools to help understand molecular orbitals, like the extended Hückel method in 1963.

Woodward–Hoffmann Rules

With another scientist named Robert Burns Woodward, Hoffmann developed the Woodward–Hoffmann rules. These rules help explain how chemical reactions happen and what shape the new molecules will have. They found that small differences in the electron orbitals of molecules can predict how a reaction will turn out. For example, their rules can predict different results if a reaction is started by heat versus light.

For this important work, Hoffmann received the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He shared the prize with Japanese chemist Kenichi Fukui, who had worked on similar ideas. Robert Burns Woodward could not receive the prize because it is only given to living people. In his Nobel speech, Hoffmann also introduced the isolobal principle. This principle helps predict how certain metal-containing compounds will bond.

More recently, Hoffmann has studied how materials behave under extreme high pressure. This is like the pressure found at the center of the Earth. He finds joy in understanding how different explanations, like physics and chemistry, come together to describe these conditions.

Connecting Science and Art

Roald Hoffmann is not just a scientist; he also has a strong interest in the arts.

The World Of Chemistry

In 1988, Hoffmann hosted a 26-episode TV show called The World of Chemistry. This show was part of a PBS education series. Hoffmann explained scientific ideas, while another person, Don Showalter, did demonstrations to help viewers understand.

Entertaining Science

Since 2001, Hoffmann has hosted a monthly series called Entertaining Science. This series takes place in New York City and explores how art and science are connected.

Books and Poetry

He has written books about the links between art and science. These include Roald Hoffmann on the Philosophy, Art, and Science of Chemistry and Beyond the Finite: The Sublime in Art and Science.

Hoffmann is also a poet. Some of his poetry collections are The Metamict State (1987) and Gaps and Verges (1990). He also co-produced Chemistry Imagined (1993) with artist Vivian Torrence.

Plays

He co-wrote a play called Oxygen with Carl Djerassi. This play is about the discovery of oxygen and what it's like to be a scientist. Hoffmann has also written other plays, including "Should've" (2006), which is about ethics in science and art. Another play, "Something That Belongs to You" (2009), is based on his experiences during the Holocaust.

Awards and Recognition

Roald Hoffmann has received many honors and awards for his work.

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

In 1981, Hoffmann received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He shared it with Kenichi Fukui. They were honored "for their theories, developed independently, concerning the course of chemical reactions."

Other Awards

Hoffmann has won many other awards and has received more than 25 honorary degrees from universities. Some of his notable awards include:

- ACS Award in Pure Chemistry, 1969

- Arthur C. Cope Award in Organic Chemistry, 1973 (with Robert B. Woodward)

- National Medal of Science, 1983

- Priestley Medal, 1990

- American Institute of Chemists Gold Medal, 2006

- Lomonosov Gold Medal, 2011

He is a member of the International Academy of Quantum Molecular Science. In 2007 and 2017, the American Chemical Society held special events to celebrate his 70th and 80th birthdays.

In 2018, the Hoffmann Institute of Advanced Materials was founded in Shenzhen, China, and named in his honor. In 2023, Roald Hoffmann was recognized by the Carnegie Corporation of New York with a Great Immigrants Award.

See also

In Spanish: Roald Hoffmann para niños

In Spanish: Roald Hoffmann para niños

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |