Robert Knox facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Knox

FRSE FRCSE

|

|

|---|---|

Robert Knox, c. 1830

|

|

| Born | 4 September 1791 Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Died | 20 December 1862 (aged 71) Hackney, London, England

|

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Anatomist, ethnologist |

Robert Knox (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a Scottish expert in anatomy and ethnology. Anatomy is the study of the body's structure, and ethnology is the study of different human groups.

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox became a popular teacher of anatomy. He taught a new idea called transcendental anatomy. However, some of his ways of getting bodies for study were not careful before a law called the Anatomy Act 1832 was passed. This, along with disagreements with other experts, hurt his career in Scotland. He then moved to London, but his career did not fully recover there.

Over time, Knox's ideas about people changed. He also spent his later years studying and writing about evolution and ethnology. His work on ethnology, which included ideas about different human groups, was later seen as controversial and harmful. These ideas have largely overshadowed his other contributions.

Contents

Robert Knox's Life Story

Early Years in Scotland

Robert Knox was born in 1791 in Edinburgh. He was the eighth child in his family. When he was a baby, he got smallpox, which damaged his left eye and changed his face. He went to the Royal High School of Edinburgh, where he was known for being a strong student. He even won a special gold medal in his last year.

In 1810, he started studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh. He became very interested in the ideas of transcendentalism, which looks at the deeper meaning of things. He also joined a student club called the Royal Physical Society. Although he struggled with his anatomy exam at first, he worked hard and passed it the second time.

Time Abroad and Army Service

Knox finished university in 1814. He joined the army as a Hospital Assistant in 1815. He was sent to Belgium to help soldiers wounded in the Battle of Waterloo. He used a new method to treat wounds, which helped many soldiers. His time in the army showed him how important it was for surgeons to know a lot about anatomy.

In 1817, he went to South Africa with the army. He found the people there healthy and had light duties. He enjoyed riding and observing the landscape. He also became interested in studying different human groups. He did not like how some European settlers treated the local people. However, he got into trouble after an argument with another officer. This led to a duel and his promotion was cancelled. He returned to Britain in 1820.

After this, he went to Paris for a year (1821–1822) to study anatomy more. There, he met famous scientists like Georges Cuvier and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, who became his heroes.

Teaching Anatomy in Edinburgh

Knox came back to Edinburgh in 1822. In 1823, he became a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He also helped create a museum for comparing different animal bodies.

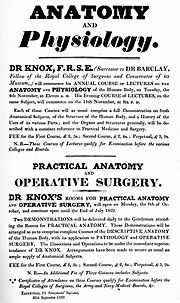

In 1825, his former teacher, John Barclay, asked him to join his anatomy school. Knox became very popular, teaching more students than all other private teachers combined. He was known for his sharp wit and interesting lectures. Even John James Audubon, a famous bird artist, visited Knox's dissecting room and found it very intense. Knox's school grew, and he hired three assistants.

Family Life

Not much is known about Knox's wife, Susan, whom he married in 1824. They had seven children, but sadly, only two lived to be adults. During his time in Edinburgh, Knox lived in one place with his sisters, while his wife and children lived in another nearby.

Later Years in London

After his wife passed away, Knox moved to London. He found it hard to get a university job. From then until 1856, he wrote for medical journals, gave public talks, and wrote several books. One of his most important books was The Races of Men. In this book, he wrote about his ideas that each human group was best suited for its own environment. His book about fishing was also very popular.

In 1854, his son Robert died. Knox tried to get a job in the army again, but at 63, he was considered too old. In 1856, he became an anatomist at the Free Cancer Hospital in London. He continued working there until shortly before he died on 20 December 1862. He was buried in Brookwood Cemetery.

Ideas on Human Groups

Knox became interested in different human groups when he was a student. He believed that each group had certain traits and was best suited for its environment. In his book The Races of Men (1850), he wrote about these ideas. He thought that some groups were more advanced than others, which is a view that is now considered wrong and harmful.

He also had very strong opinions about people from Ireland and parts of Scotland and Wales. He believed that these groups were "Celtic" and had certain negative traits. He even suggested that people should be forced to leave their land. These ideas are now seen as very prejudiced and incorrect.

Transcendentalism and Nature

Knox's way of looking at nature was shaped by important scientists of his time. He learned about the long periods of Earth's history and how some animals became extinct. He also believed that all living things were connected and followed certain patterns.

He was also influenced by the German writer Goethe, who thought there were perfect "archetypes" or basic forms in the natural world. Knox believed that if you studied animals in the right order, you could see these perfect forms. He wanted to show that animals were related by their general type, not just by their specific kind.

Ideas on Evolution

Knox also had ideas about evolution, which is how living things change over time. He thought that new species might appear suddenly, not just through slow changes. He wondered if simple animals could have led to more complex ones, like fish leading to reptiles, birds, and then humans. He believed that new species survived or died out based on their environment.

One reviewer at the time found his ideas about species changing over millions of years to be very bold. Knox believed that species could transform into others, especially if they already shared many characteristics when they were young. He thought that all living things were related, from species to larger groups.

Legacy and Recognition

Robert Knox is remembered in the scientific name of a type of African lizard, Meroles knoxii.

Works by Robert Knox

- Engravings of the nerves: copied from the works of Scarpa, Soemmering and other distinguished anatomists. Edinburgh 1829.

- The races of men: a fragment. Renshaw, London. 1850, revised 1862.

- Great artists and great anatomists: a biographical and philosophical study. Van Voorst, London 1852.

- A manual of artistic anatomy 1852.

- Fish and fishing in the lone glens of Scotland, with a history of the propagation, growth and metamorphoses of the Salmon. Routledge, London 1854.

- Man – his structure and physiology 1857.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Robert Knox (anatomista) para niños

In Spanish: Robert Knox (anatomista) para niños