Rose Schneiderman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rose Schneiderman

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | April 6, 1882 Sawin, Congress Poland

|

| Died | August 11, 1972 (aged 90) New York City, New York, US

|

| Occupation | Labor union leader |

| Partner(s) | Maud O'Farrell Swartz (d. 1937) |

Rose Schneiderman (born April 6, 1882 – died August 11, 1972) was an important American leader. She was born in Poland. Rose was a strong voice for workers' rights and women's rights. She was a socialist and a feminist.

As part of the New York Women's Trade Union League, she showed how dangerous workplaces could be. This was especially true after the terrible Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911. She also worked hard for women's right to vote. She helped pass a law in New York in 1917 that gave women this right.

Rose Schneiderman also helped start the American Civil Liberties Union. She worked for President Franklin D. Roosevelt on his Labor Advisory Board. She is famous for saying "Bread and Roses." This phrase means that workers deserve more than just enough to live. They also deserve beauty and joy in their lives.

Contents

Early Life

Rose Schneiderman was born Rachel Schneiderman on April 6, 1882. She was the first of four children in a Jewish family. They lived in a village called Sawin in Poland. Her parents, Samuel and Deborah, worked with sewing.

Rose first went to a Hebrew school in Sawin. This school was usually only for boys. Then she went to a public school in Chełm. In 1890, her family moved to the Lower East Side of New York City.

Rose's father died in 1892. This left her family very poor. Her mother worked hard as a seamstress. But sometimes, they had to put the children in a Jewish orphanage. Rose left school in 1895 after the sixth grade. She wanted to keep learning, but she had to work. She first worked as a cashier. Later, in 1898, she stitched linings in a cap factory.

In 1902, Rose and her family moved to Montreal for a short time. There, she became interested in politics and labor unions.

Working for Change

Rose came back to New York in 1903. She and a friend started to organize the women in her factory. They wanted to form a union. The United Cloth Hat and Cap Makers Union told them to come back when they had 25 women. They did this in just a few days! This led to the union's first local group for women.

Schneiderman became well-known during a capmakers' strike in 1905. She was chosen as secretary of her local union. She also became a delegate to the New York City Central Labor Union. There, she met the New York Women's Trade Union League (WTUL). This group helped women workers with money and support.

Rose quickly became a top member of the WTUL. In 1908, she was elected vice president of the New York branch. She left the factory to work full-time for the league. She even went to school with money from a wealthy supporter. She was very active in the "Uprising of the 20,000" in 1909. This was a huge strike by shirtwaist workers in New York City. She also helped at the first 1919 International Congress of Working Women in 1919. This meeting worked to improve conditions for women workers.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire happened in 1911. In this terrible fire, 146 garment workers died. They either burned or jumped from the ninth floor of the factory. This event showed everyone how dangerous workplaces were. Rose Schneiderman, the WTUL, and unions had been fighting these conditions.

The WTUL had already found many unsafe factories. These places had no fire escapes or locked exit doors. This was done to stop workers from stealing materials. Before the Triangle fire, 25 workers had died in a similar fire in Newark, New Jersey.

Rose Schneiderman spoke at a memorial meeting on April 2, 1911. She was very angry about what happened. She spoke to a crowd that included many wealthy WTUL members:

I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting. The old Inquisition had its rack and its thumbscrews and its instruments of torture with iron teeth. We know what these things are today; the iron teeth are our necessities, the thumbscrews are the high-powered and swift machinery close to which we must work, and the rack is here in the firetrap structures that will destroy us the minute they catch on fire.

This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 143 of us are burned to death.

We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers and brothers and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

Public officials have only words of warning to us – warning that we must be intensely orderly and must be intensely peaceable, and they have the workhouse just back of all their warnings. The strong hand of the law beats us back, when we rise, into the conditions that make life unbearable.

I can't talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.

Even after these strong words, Rose kept working for the WTUL. She became president of its New York branch. Then, she became its national president for over 20 years. She stayed in this role until the WTUL closed in 1950.

In 1920, Schneiderman ran for the United States Senate in New York. She wanted to build affordable housing for workers. She also wanted better schools, public power, and health insurance for everyone.

Rose helped start the American Civil Liberties Union. She became good friends with Eleanor Roosevelt and her husband, President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1933, President Roosevelt chose her for his Labor Advisory Board. She was the only woman on this board. From 1937 to 1944, she was New York State's Secretary of Labor. She worked to get social security for house workers. She also fought for equal pay for women. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, she tried to help Jewish people escape Europe. Albert Einstein praised her efforts.

Fighting for Women's Vote

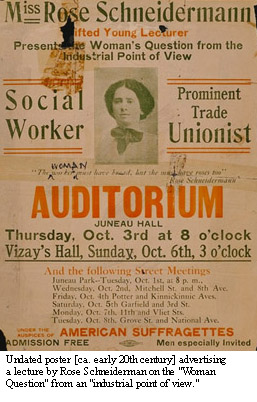

Starting in 1907, Rose Schneiderman said that women needed the right to vote. She believed this would help them improve their poor working conditions. She helped bring working-class women into the women's suffrage movement. This movement was mostly made up of middle-class women. Rose became a popular speaker for groups that focused on working women.

In 1912, she traveled through Ohio. She gave talks to working men to get their support for women's voting rights. She told them that if their wives and daughters could vote, it would greatly help labor laws. The vote did not pass in Ohio that year.

In 1917, New York was going to vote on women's suffrage. Rose was put in charge of the industrial section of the New York Women's Suffrage Association. She spoke at men's union meetings. She also shared writings and wrote open letters. These letters explained how voting could help women improve their jobs. On election day, Rose and her friends worked at three voting places. This was the first time they had seen the inside of a polling station. The vote passed, giving women in New York the right to vote.

After the Nineteenth Amendment passed in 1920, women across the U.S. could vote. Some feminists then wanted the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). This amendment would give equal rights to all citizens, no matter their sex. But Rose and other women labor activists were against the ERA. They worried it would take away special protections for working women. These protections included rules about wages, hours, and safety during pregnancy.

Legacy

Rose Schneiderman is famous for a powerful phrase. It became important for both the women's movement and the labor movement:

What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist — the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. You have nothing that the humblest worker has not a right to have also. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with.

Her phrase "Bread and Roses" became linked to a 1912 textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Many of the workers were immigrant women. Later, James Oppenheim used it as the title of a song. It was put to music by Mimi Fariña and sung by artists like Judy Collins and John Denver.

In 1949, Rose Schneiderman retired from public life. She sometimes gave radio speeches and appeared for unions. She spent her time writing her life story, called All for One, which came out in 1967.

Rose never married. She was very close to her nieces and nephews, treating them like her own children. She had a long and close friendship with Maud O'Farrell Swartz (1879–1937). Maud was also a working-class woman active in the WTUL. They were work and travel partners. They were often invited to events together and gave gifts together.

Rose Schneiderman died in New York City on August 11, 1972, when she was 90 years old. The New York Times said she taught Eleanor and Franklin D. Roosevelt a lot about unions. They also said she helped pass important laws like the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. Her obituary stated that she did "more to upgrade the dignity and living standards of working women than any other American."

See also

In Spanish: Rose Schneiderman para niños

In Spanish: Rose Schneiderman para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |