Saber–toothed cat facts for kids

The saber-toothed cats are some of the most famous extinct animals. They were impressive meat-eaters that lived a long time ago. These cats had very long, sharp canine teeth and jaws that could open much wider than modern cats. This suggests they hunted and killed their prey in a different way than today's lions or tigers.

The unique "saber-tooth" hunting style actually developed at least five different times in various groups of meat-eating mammals. This is a great example of convergent evolution, which is when different animals develop similar features or ways of life because they face similar challenges in their environment.

Here are some of the groups that developed saber teeth:

- The Creodonts: These were the earliest saber-toothed animals, living during the Eocene epoch. They were not closely related to modern cats. Examples include Machaeroides and Apataelurus.

- The Nimravids: These were an early group of cat-like mammals that lived from the Eocene to the Miocene epochs. Hoplophoneus is a well-known example.

- The Barbourofelidae: Another family of cat-like animals that developed saber teeth during the Miocene. They were probably more closely related to true cats than the Nimravids.

- The Sparassodonts: These were a group of mammals related to marsupials, like kangaroos. Thylacosmilus is an example from the Miocene to Pliocene epochs.

- The Machairodontinae: This group was a subfamily of the true cat family. They lived from the Miocene to the Pleistocene epochs (about 23 million to 11,000 years ago). This group includes the very famous Smilodon.

- Nimravides: This cat is part of the modern cat family (Felinae), and it's important to know it's *not* one of the Nimravids mentioned earlier.

Saber-toothed cats were ambush predators, meaning they would hide and then suddenly attack their prey. They likely lived in open forests, which were common during the Miocene. Besides their long canine teeth, they had very strong front legs, even stronger than today's big cats. Their heavy, tough bodies suggest they relied on strength rather than speed.

Scientists believe they hunted by hiding, then pouncing on their prey. They would grab onto the prey's neck, using their powerful front legs to hold it down. Then, they would use their long canine teeth to slash the underside of the throat. This attack would cause the prey to die from blood loss or by cutting off its air supply.

It's interesting that their teeth varied a lot. Some had very large teeth, while others had smaller, dagger-like teeth. Some teeth were smooth and thick, while others were blade-like, sometimes with jagged edges. Some saber-toothed cats even had a bony "flange" on their lower jaw, but most did not. These differences likely mean they had different ways of killing and hunted different types of prey.

No saber-toothed cats are alive today; they are all extinct. Their disappearance happened as the world's climate cooled. Grasslands began to replace woodlands during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs, changing their habitats and food sources.

Contents

Body Features of Saber-Toothed Cats

Their Amazing Skull

Scientists have studied the skulls of saber-toothed cats, especially their teeth, a lot. Because there are many different types of saber-toothed cats, good fossils, and modern cats to compare them to, these ancient predators help us understand how specialized meat-eaters lived and how predators and prey interacted.

Saber-toothed cats are often put into two groups: "dirk-toothed" and "scimitar-toothed."

- Dirk-toothed cats had long, narrow upper canine teeth and usually had strong, stocky bodies. Smilodon is an example.

- Scimitar-toothed cats had wider and shorter upper canines. They typically had lighter, more flexible bodies with longer legs. Homotherium is an example.

- One cat, Xenosmilus, was unusual because it had the heavy limbs of a dirk-toothed cat but the stout canines of a scimitar-toothed cat!

Meat-eating animals tend to have fewer teeth as they become more specialized in eating only meat, rather than grinding plants or insects. Cats already have fewer teeth than most other meat-eaters, and saber-toothed cats had even fewer. Most saber-toothed cats had six incisors (front teeth), two canines, and six premolars (teeth behind the canines) in each jaw. They also had two molars (back teeth) only in their upper jaw. Some, like Smilodon, had even fewer premolars. Their canines curved smoothly backward, and any small serrations (saw-like edges) wore away as they got older. These details help scientists guess the age of a fossilized saber-toothed cat.

How They Opened Their Jaws So Wide

Longer canine teeth mean an animal needs to open its mouth much wider. A modern lion can open its mouth about 95 degrees. If it had nine-inch long canines, it wouldn't be able to open its mouth enough to use them effectively. Saber-toothed cats, and other animals that developed similar teeth, had to change their skulls to make room for these huge teeth.

The main muscles that limit how wide a mammal can open its mouth are the temporalis and masseter muscles at the back of the jaw. These muscles are usually very strong but not very stretchy. To open their mouths wider, saber-toothed cats needed to make these muscles smaller and change their shape.

One way they did this was by reducing a bony part of the jaw called the coronoid process. Since the jaw muscles attach here, making this part smaller meant the muscles could be smaller. Smaller muscles allowed for more stretch and less resistance to a wide opening. This change also made the temporalis muscle longer and more compact, which is better for stretching. However, this also meant they had a weaker bite force.

The skulls of saber-toothed cats also show another change in the temporalis muscle. When a cat opens its mouth very wide, this muscle can get stretched too much around a part of the skull called the glenoid process. To prevent this, saber-toothed cats developed a skull where the back part (the occipital bone) was more upright. A domestic cat can open its mouth 80 degrees, and a lion 91 degrees. But Smilodon could open its mouth an amazing 128 degrees! This was possible because the angle of its occipital bone allowed for a much wider gape.

The skulls of many saber-toothed predators were also tall from top to bottom and short from front to back. The cheekbones (zygomatic arches) were compressed, and the part of the skull with the eyes was higher, while the snout was shorter. These changes helped them open their mouths so wide. Saber-toothed cats also had smaller lower canine teeth, which helped keep space between their upper and lower jaws.

Special Features and Diet

Bite Strength

The jaws of saber-toothed cats, especially those with longer canines like Smilodon and Megantereon, were surprisingly weak. Computer models of lion and Smilodon skulls show that Smilodon would have struggled to hold onto struggling prey using only its jaw muscles. The main problem was that strong forces could break their lower jaw at its weakest points.

Smilodon would have had only about one-third the bite force of a lion if it only used its jaw muscles. However, they had very strong neck muscles that connected to the back of their skull. When they opened their jaws very wide, these neck muscles would push their head down, forcing their canines into whatever they were biting. Once the mouth was closed enough, the jaw muscles could then help a bit.

What They Ate

Sometimes, the bones of fossilized predators are so well preserved that they still contain tiny traces of the proteins from the animals they ate. By studying these proteins, scientists have learned that Smilodon mainly hunted bison and horses. They also sometimes ate giant ground sloths and mammoths. Homotherium, another saber-toothed cat, often hunted young mammoths and other grazing animals like pronghorn antelope and bighorn sheep when mammoths weren't available.

Their Face

Some paleontologists have suggested what the soft parts of saber-toothed cats, like Smilodon, might have looked like.

One idea was that they had lower ears, or at least their ears looked lower because of a high ridge on their skull. However, modern cats always have their ears in a similar position, even if they have skull ridges. So, how their ears looked (big or small, pointed or rounded) is mostly up to the artist drawing them, as fossils don't show these details.

Another idea was that they had a pug-like nose. But aside from pugs and similar dog breeds, no modern meat-eating animal has a pug nose naturally. This trait is usually created by selective breeding. So, this idea is generally not accepted by scientists.

A third idea was that their lips were much longer, perhaps 50% longer than a modern cat's. This idea is still used in many modern drawings of saber-toothed cats. The argument was that longer lips would allow for more stretch when biting prey with such a wide gape. However, some scientists disagree, saying that modern cats' lips are already very stretchy and would be enough. Despite this debate, many artists still draw saber-toothed cats with long lips, sometimes looking like the jowls of large dogs.

Studies of Homotherium and Smilodon suggest that scimitar-toothed cats like Homotherium had upper lips and gums that could completely hide and protect their long upper canines, just like modern cats. But Smilodon had such long canines that they likely stuck out a bit past their lips and chin even when their mouth was closed.

How They Sounded

By comparing the hyoid bones (small bones in the throat that support the tongue and voice box) of Smilodon and modern lions, scientists think that Smilodon and possibly other saber-toothed cats could have roared like their modern relatives. However, a recent study in 2023 suggested that while saber-toothed cats had the same number of hyoid bones as "roaring" cats, their shape was actually closer to that of "purring" cats. So, it's still a bit of a mystery!

Images for kids

-

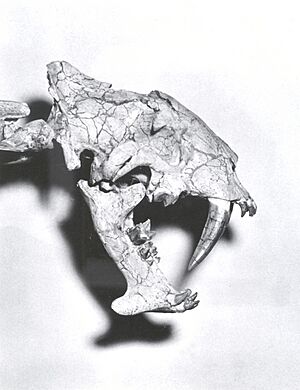

Reconstruction of a Smilodon

-

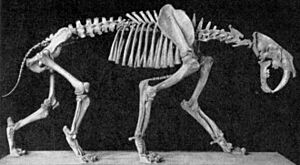

4th saber-tooth instance: Machaeroides skull.

See also

In Spanish: Macairodontinos para niños

In Spanish: Macairodontinos para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |