Santōka Taneda facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Taneda Santōka

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

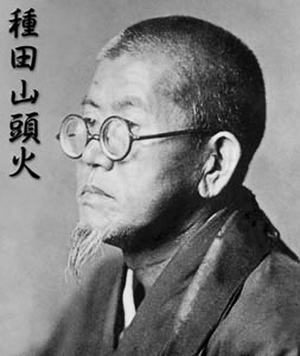

Photo of Taneda Santōka

|

|||||

| Born | December 3, 1882 |

||||

| Died | October 11, 1940 (aged 57) | ||||

| Other names | 種田 山頭火 | ||||

| Occupation | Haiku poet | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 種田 山頭火 | ||||

| Hiragana | たねだ さんとうか | ||||

|

|||||

Santōka Taneda (種田 山頭火 ([Taneda Santōka] Error: {{nihongo}}: text has italic markup (help)), born December 3, 1882 – died October 11, 1940) was the pen-name of Shōichi Taneda (種田 正一 ([Taneda Shōichi] Error: {{nihongo}}: text has italic markup (help))). He was a Japanese author and haiku poet. He is famous for his free verse haiku. This style does not follow the usual rules of traditional haiku.

Early Life

Santōka was born in a village in Honshū, Japan's main island. His family owned a lot of land and was wealthy. When he was eleven, his mother died by throwing herself into the family well. The exact reason for her action is not fully known, but it was a very sad event for the family. After this, Santōka was raised by his grandmother.

In 1902, he started studying literature at Waseda University in Tokyo. He had to leave university early due to health issues. At that time, his father, Takejirō, was having money problems and could barely pay for Santōka's studies.

In 1906, Santōka and his father sold some family land. They used the money to open a sake brewery. In 1909, his father arranged for Santōka to marry Sato Sakino, a girl from a nearby village. In 1910, Sakino gave birth to their son, Ken.

Life as a Poet

In 1911, Santōka started publishing his writings. He translated works by famous authors like Ivan Turgenev and Guy de Maupassant. He published them in a magazine called Seinen (Youth) using the pen name Santōka (山頭火). This name means "Mountain-top Fire."

That same year, Santōka joined a local haiku group. At first, his haiku poems mostly followed the traditional 5-7-5 syllable rule. Here is an example:

- In a café we debate decadence a summer butterfly flits

- Kafe ni dekadan o ronzu natsu no chō toberi

In 1913, Santōka became a student of Ogiwara Seisensui. Seisensui was a leading haiku reformist. He is seen as the creator of the free-form haiku movement. Other writers like Masaoka Shiki and Kawahigashi Hekigoto also helped this movement. Free-form haiku (called shinkeikō or 'new trend') did not follow the 5-7-5 syllable rule. They also did not need a special seasonal word (kigo).

Santōka began writing poems regularly for Seisensui's haiku magazine, Sōun (Layered Clouds). By 1916, he became an editor for the magazine.

However, 1916 was also a difficult year. His father's sake brewery went bankrupt. The family lost all their money. His father went into hiding. Santōka moved his family to Kumamoto City. There, he opened a picture frame shop. Later, Santōka's grandmother died. In 1919, Santōka left his family to find a job in Tokyo. In 1920, he divorced his wife, Sakino. His father died soon after.

Santōka was not good at keeping a steady job. In 1920, he became a librarian, but by 1922, he was unemployed again due to health issues. He was in Tokyo during the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. After the earthquake, he was wrongly arrested as a suspect. Once released, he returned to Kumamoto City. He helped Sakino with her shop.

One day, Santōka tried to end his life by lying on train tracks. The train stopped just in time. A newspaper reporter took him to the Sōtō Zen temple Hōon-ji. The head priest, Mochizuki Gian, welcomed him. Santōka found peace in the Zen life. The next year, at age forty-two, he became a monk in the Sōtō sect.

In 1926, Santōka started his first long walking trip. He had spent a year taking care of the Mitori Kannon-dō temple. He was away for three years. During this time, he completed the Shikoku Pilgrimage, visiting eighty-eight temples on Shikoku Island. He also visited the grave of his friend, Ozaki Hōsai.

In 1929, he briefly returned to Kumamoto. He visited Sakino and published more haiku in Sōun. He also started his own publication, Sambaku. Soon, he was back on the road.

During his trips, Santōka wore his priest's robe. He also wore a large bamboo hat called a kasa to protect himself from the sun. He carried one bowl for begging and eating. To survive, he went from house to house to beg for food and money. Begging (takuhatsu) is a part of practice for monks in Japan. However, since Santōka was not part of a monastery, he was sometimes looked down upon. He was even questioned by the police a few times. The money he earned each day paid for a room at a guesthouse, food, and sake.

In 1932, Santōka lived for a while in a small house in Yamaguchi prefecture. He called it “Gochūan.” There, he published his first book of poems, Hachi no ko (“Rice Bowl Child”). He lived on money from friends, what he grew in his garden, and money from his son Ken. In 1934, he started another walking trip but became very ill. He had to return home. In 1936, he began to walk again. He wanted to follow the path of the famous haiku poet Bashō. Bashō's journey is described in Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Interior). Santōka returned to Gōchuan after eight months.

In 1938, Gochūan became too old to live in. After another walking trip, Santōka settled at a small temple near Matsuyama City. On October 11, 1940, Santōka died in his sleep. He had published seven collections of poems and many editions of Sambaku. He was fifty-seven years old.

Poetry

Here is a famous example of Santōka's poetry:

What, even my straw hat has started leaking

笠も漏り出したか

kasa mo moridashita ka

This poem shows two main things about free verse haiku:

- It is a single thought and does not have the 5-7-5 syllable pattern.

- It does not contain a specific season word.

However, the poem does hint at rain. It talks about a straw hat and how it is leaking. This suggests a natural event.

Here are more examples of free haiku poems by Santōka:

- From Hiroaki Sato’s translation of Santōka's Grass and Tree Cairn:

- I go in I go in still blue mountains

- Wakeitte mo wakeitte mo aoi yama

- Fluttering ... leaves scatter

- Horohoro yōte ki no ha chiru

- From Burton Watson’s translation For All My Walking:

- there

- where the fire was

- something blooming

- yake-ato nani yara saite iru

- feel of the needle

- when at last

- you get the thread through it

- yatto ito ga tōtta hari no kanshoku

|

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |