Santa María de Óvila facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Santa María de Óvila |

|

|---|---|

The ruins of Santa María de Óvila in Spain, shown more than 75 years after the most striking architectural features were removed by agents of William Randolph Hearst

|

|

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic Church |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Abbey |

| Year consecrated | 1213 |

| Status | Abandoned |

| Location | |

| Location | Trillo, Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, Spain |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural type | Monastery, Church |

| Architectural style | Gothic, Renaissance |

| Groundbreaking | 1181 |

| Completed | 1213 |

| Official name: Monasterio de Santa María Óvila | |

| Type | Monument |

| Designated | 4 June 1931 |

| Reference no. | (R.I.)-51-0000612-00000 |

The Santa María de Óvila was once a Cistercian monastery in Spain. Its construction started in 1181 near the Tagus River in Trillo, Guadalajara, about 90 miles (145 km) northeast of Madrid. In 1835, the Spanish government took control of it and sold it to private owners.

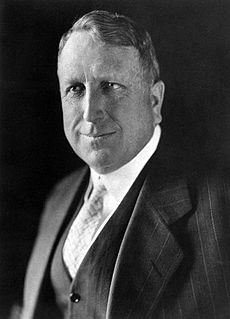

In 1931, an American newspaper owner named William Randolph Hearst bought parts of the monastery. He planned to use its ancient stones to build a huge, imaginative castle in California. About 10,000 stones were carefully taken apart and shipped across the ocean. However, they were left in San Francisco for many years.

Today, these stones are in different places in California. The old church entrance, called a portal, was put back together at the University of San Francisco. The chapter house, a special meeting room, was rebuilt by Trappist monks at the Abbey of New Clairvaux in Vina, California. Other stones are used as decorations in Golden Gate Park's botanical garden.

Back in Spain, the new government declared the monastery a National Monument in June 1931. But this happened too late to stop the removal of many stones. What's left of the monastery buildings and walls now stands on private farmland.

History of the Monastery

How the Monastery Started

The Santa María de Óvila monastery began in 1175. King Alfonso VIII of Castile gave land to the Cistercian monks from Valbuena Abbey in Spain. The king wanted to set up Catholic places on land he had recently won from the Moors.

The Cistercian monks, known as "white monks" because of their plain clothes, first chose a spot by the Tagus River. But after a few years, they moved to a better, more fertile area closer to Trillo, Guadalajara. This new spot was a flat hilltop with a nice view of the river.

Construction started in 1181. The monks' living areas and the church were built over the next 30 years. The main cloister (an open courtyard) was surrounded by the church, a large hall, a sacristy (where sacred items are kept), the chapter house, and the kitchen and dining hall. Some buildings had very thick walls, about 7 feet (2 meters) wide, with narrow windows. These were built to protect the monks if the Moors returned. The church was shaped like a Latin cross, with a main hall divided into four parts.

In 1191, the king officially confirmed that the monastery and its lands belonged to the Cistercian Order. In September 1213, the church was officially blessed by Abbot Martín de Finojosa. The areas around the monastery grew and gave money and land to the monks. Important historical documents about the monastery are kept at the University of Madrid.

Building Styles and Changes

The first buildings, including the church, were built in the Gothic style. The dining hall showed a mix of older Romanesque and newer Gothic styles. A beautiful chapter house was built using high-quality limestone. The church was rebuilt around 1650 in a later Gothic style with a grand vaulted ceiling.

The cloister was rebuilt around 1617. It had a simple design with an arcade (a series of arches) from the Renaissance period. The last building work happened around 1650, adding a new, detailed doorway to the church in a late Renaissance style. Because the monastery was successful and expanded many times, it showed examples of every Spanish religious building style from 1200 to 1600. Even at its busiest, Óvila was one of the smaller Cistercian monasteries in the Castile region.

The Monastery's Decline

Starting in the 1400s, the Santa María de Óvila monastery slowly began to decline. Wars in the area caused villages to lose people. The monastery's lands gradually went to new powerful families and the Spanish Army. Neighbors also took some of its lands.

A fire damaged part of the monastery during the War of the Spanish Succession. Later, during the Peninsular War, French soldiers looted the buildings and used them as barracks (places for soldiers to live). The monks had to leave in 1820 because a new government took church property. They returned in 1823 when the king brought back older traditions.

However, the nearby villagers didn't support the monastery. It finally stopped operating in 1835. A new law stated that small religious places with fewer than 12 residents would be taken by the state. The monastery only had four monks and one helper, so they were forced to leave.

After the Monks Left

After the government took the monastery, many of its valuable items and artworks were moved to nearby churches. Other things, like books and old documents, were stolen and sold. The remaining items, including wine-making tools, were sold at auction. A very important 328-page book of royal documents about the monastery was bought by a private owner. It was later given to another monastery in 1925. This book also contained a detailed history of the abbots and monks who lived there.

The new owners of Santa María de Óvila were farmers who didn't care much for the buildings. For a short time, it was used as a guesthouse. But mostly, the buildings were used for farming, like barns for animals. The chapter house even became a place to store manure. Other buildings were used for storage. In the early 1900s, small trees were seen growing on the monastery roofs because the protective roof tiles had been taken down and sold.

Moving to California

In 1928, the Spanish government sold the monastery to Fernando Beloso for a small amount of money. In 1930, Arthur Byne, an art agent in Madrid, was looking for an old monastery for his main client, American newspaper owner William Randolph Hearst. Byne had previously helped Hearst buy another monastery in 1925, which was taken apart and shipped to New York.

Beloso invited Byne to see the Óvila monastery in December 1930. Byne then sent pictures and drawings to Hearst. Byne listed specific parts to be removed, like archways, door frames, window openings, columns, and decorative tops. He even suggested taking entire walls of beautiful stones. He called the project "Mountolive" to try and hide it from Spanish officials who protected historical items.

Hearst loved the idea. Beloso sold Byne the stones for $85,000, which included the cloister, chapter house, dining hall, and novice dormitory. With Byne's fee, Hearst paid about $97,000. Byne quickly started the project, organizing workers and materials to remove the stones. Hearst's main architect, Julia Morgan, sent her assistant, Walter T. Steilberg, who arrived in March 1931. Steilberg suggested Hearst also buy the old church entrance, which he did for $1,500.

Under Byne and Steilberg's guidance, the monastery was carefully taken apart stone by stone. A local foreman named Antonio Gomez numbered the blocks on drawings and painted the numbers in red on the back of each stone.

To move the many stones, Byne and Steilberg built a road to the Tagus River. A special barge was used to carry stones across the river. An old World War I trench railway was brought in to move stones from the monastery buildings to the ferry. Workers pushed small rail cars along the tracks. Cranes then lifted the stones onto the ferry and then onto trucks. One big challenge was that Spain's factories couldn't make enough packing material for all the crates. Steilberg suggested slicing the stones thinner to make them easier to ship, but Hearst wanted the full-sized stones. Byne and Steilberg left some less important walls and buildings in Spain.

Byne hurried the project because he feared the authorities might stop it. Spanish law did not allow the removal of historical items. However, the Spanish government was in a difficult situation and didn't enforce the law at first. Officials "looked the other way" as trucks carried 700-year-old stones to the docks. When the king left Spain in April 1931, the new government stopped the project. Byne's lawyer convinced them to let the work continue, arguing that it employed over a hundred men and helped the struggling economy.

Doctor Francisco Layna Serrano had tried for years to save the monastery but couldn't get the government interested. Realizing this was his last chance to record the monastery before it was gone, he wrote a book about its history and drew a map of its layout from memory. Because of his efforts, on June 3, 1931, Santa María de Óvila was officially named a National Monument of Spain. Layna Serrano published his book in 1932. In 1933, the monastery's historical documents were brought to the University of Madrid and published.

By the time the dismantling finished on July 1, 1931, about 10,000 stones, weighing a total of 2,200 short tons (2,000 metric tons), had been shipped on 11 different cargo ships through the Panama Canal to San Francisco. The entire monastery project cost Hearst about one million dollars at that time.

The Ruins in Spain Today

Today, only a few buildings remain of the original monastery in Spain. These include the winery, which is now the oldest building still standing on the site. It was built in the 1200s. Outside the winery, crumbling walls, open areas, and part of the church's Gothic roof can be seen. The double arches in the walls of the Renaissance-era cloister are still there, but the arched roof is gone. The foundation of the church can also be seen.

The Monastery in California

Hearst's Wyntoon Plan

Hearst first bought the monastery stones to rebuild his family's retreat at Wyntoon, near Mount Shasta in Northern California. His mother's original chalet (a type of house) had burned down in 1929. Hearst wanted to replace it with a large stone building with towers and turrets, a unique castle that would be even bigger than the old one.

To get ready for the Spanish stones, architect Julia Morgan drew plans. The monastery's chapter house was to be the castle's entrance hall, and the large church would hold a swimming pool. Other stones were planned to cover walls and rooms on the ground floor.

At the Port of San Francisco, Walter Steilberg checked each shipment of stones, which came in thousands of crates. A warehouse near Fisherman's Wharf was used for storage. Hearst had planned to start building in July 1931, but he stopped his grand plan for Wyntoon. His wealth had greatly decreased because of the Great Depression. The stones stayed in the warehouse, costing $15,000 a year in storage fees.

Stones in Golden Gate Park

In 1940, Hearst decided to give the monastery stones away. The government of Spain asked for them back, but Hearst refused. In August 1941, the director of the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum convinced Hearst to give the stones to the City of San Francisco. In return, the city would pay Hearst's $25,000 storage debt. Hearst said the stones should be used to build museum buildings next to the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park.

The city moved the crates from the warehouse to store them outdoors behind the museum and the Japanese Tea Garden. They only had $5,000 for moving and building simple shelters. The museum plan was estimated to cost $500,000, but that money wasn't available. Julia Morgan drew several plans for the city, showing different ways to arrange the buildings. However, in December 1941, the U.S. entered World War II, and the museum plans were put on hold.

In 1946, the city continued the project. They paid Morgan to build a small model of the planned Museum of Medieval Arts, which was meant to be like The Cloisters in New York. But the city couldn't raise enough money to build the museum. The stones were also damaged in five fires. The first fire happened soon after the crates were placed in Golden Gate Park. Morgan said that "piles of burning boxes were pulled over and down by the Fire Department."

Hearst passed away in 1951, and Morgan in 1957. Neither of them saw anything built with the stones. Two fires in 1959 seemed to be set on purpose. Many stones were weakened or cracked from being heated by fire and then suddenly cooled by water. In 1960, Steilberg was hired again to check the stones. He tapped each stone with a hammer to hear if it made a solid sound or a dull thud, which meant it was cracked. He found that a little more than half the stones were still good.

In 1965, a museum group raised $40,000 to put up the grand entrance of the old church. It was placed in the de Young Museum as the main feature of Hearst Court. The rest of the stones were left by the museum in May 1969, with the announcement that they would not be rebuilt. After this, park workers sometimes took stones to decorate Golden Gate Park.

In 1999, some of the stones were used to build an outdoor reading area next to the Helen Crocker Russell Library of Horticulture, which is part of the Strybing Arboretum and Botanical Gardens in Golden Gate Park. Other stones were used for various purposes around Golden Gate Park and the Japanese Tea Garden, sometimes taken unofficially by park workers. Some ended up in the park's AIDS Memorial Grove, and others on a flower walkway called the Garden of Fragrance.

University of San Francisco Display

In 2002, the old church entrance was given by the de Young Museum to the University of San Francisco (a Jesuit university). In 2008, it was used in the construction of Kalmanovitz Hall. It now serves as the background for the outdoor Ovila Amphitheater (37°46′33″N 122°27′04″W / 37.7757°N 122.451°W), near an older Romanesque entrance from Northern Italy.

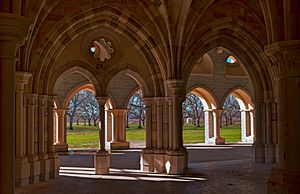

Rebuilding at Abbey of New Clairvaux

The Abbot-Emeritus of the Abbey of New Clairvaux, Thomas X. Davis, first saw the stones on September 15, 1955. He imagined them put back together in a monastery setting. He had just arrived in Vina, California, to be a new monk at the Trappist monastery called Our Lady of New Clairvaux. It was on land once used by Leland Stanford for vineyards. Davis's superior drove him through Golden Gate Park and showed him the stones sitting among the weeds. Over the years, Davis visited the stones and saw them getting worse.

In 1981, a historian named Margaret Burke started working to list all the remaining stones. She said it was like an "excavation project" because of all the weeds and tree roots growing over them. Burke identified about 60% of the stones that belonged to the chapter house, a rectangular building. She separated these stones, put a fence around them, and started making patterns to rebuild the arched entrances.

Meanwhile, Davis asked a museum staff member if he could take several truckloads of stones to Vina for decoration. Park workers helped him load the most decorative pieces he could find. Burke later found out that Davis had taken some of the chapter house stones, and the museum insisted they be returned. Davis was left with 58 stones from other monastery buildings.

In 1983 and 1987, Davis tried to get all the chapter house stones, but he was not successful. After the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the de Young museum was going to be rebuilt, and the future of the stones was discussed again. In September 1993, the museum director and Davis signed an agreement to permanently loan the chapter house stones to New Clairvaux. In 1994, the city approved the loan, saying the building had to be rebuilt accurately and open to the public sometimes. The stones were transported in 20 truckloads to Vina. Inside an old brick barn, the stones began to be fitted together, laid flat on Burke's patterns.

Construction began in 2003 on the site of an orchard (39°56′14″N 122°03′48″W / 39.9372°N 122.0632°W) next to the main cloister building. Architect Patrick Cole, who oversaw the rebuilding, said they had more than half of the stones needed for the chapter house. For the missing stones, over 90% were repeating patterns, so they had templates to carve new ones. Stonemasons Oskar Kempf and Frank Helmholz used modern hydraulic lime as mortar. Helmholz said it was a special opportunity that most stonemasons don't get in their careers.

The rebuilt building is now twice as strong as it was in Spain. The stones support their own weight, as designed, but they are also held together by an outside frame of steel and concrete to make them strong during California earthquakes. The contractor said the building's foundation was also earthquake resistant, with a thick mat of concrete and steel underneath, so "the entire building will move as one unit." The reassembled chapter house is the largest example of original Cistercian Gothic architecture in the Western Hemisphere. It is also the oldest building in America west of the Rocky Mountains.

The Sierra Nevada Brewing Company partnered with the monks of New Clairvaux to make a series of Belgian-style beers under the Ovila Abbey brand. In late 2010, the beer company launched a website to share the story of the beer and the stone restoration. Sierra Nevada's founder, Ken Grossman, had wanted to make Belgian beers for a long time, and the abbey's project was a good chance. The first beer was released in March 2011, followed by others. Sierra Nevada has given a percentage of the beer sales to help fund the rebuilding project.

See also

In Spanish: Monasterio de Santa María de Óvila para niños

In Spanish: Monasterio de Santa María de Óvila para niños