The Cloisters facts for kids

View of the main entrance

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Established | May 10, 1938 |

|---|---|

| Location | 99 Margaret Corbin Drive, Fort Tryon Park Manhattan, New York City |

| Type | Medieval art Romanesque architecture Gothic architecture |

| Public transit access | Subway: Bus: Bx7, M4, M100 |

|

The Cloisters

|

|

|

U.S. Historic district

Contributing property |

|

| Built | 1935–1939 |

| Architect | Charles Collens |

| Part of | Fort Tryon Park and the Cloisters (ID78001870) |

| Significant dates | |

| Designated CP | December 19, 1978 |

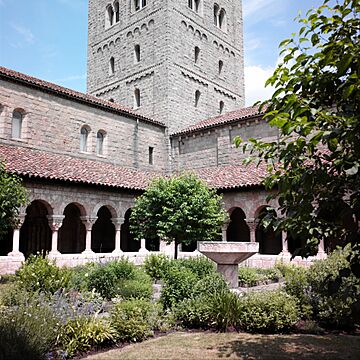

The Cloisters, also known as the Met Cloisters, is a special museum in Fort Tryon Park in New York City. It's located in Upper Manhattan, between the Washington Heights and Inwood neighborhoods. This museum focuses on European medieval art and buildings from the Romanesque and Gothic times.

The Cloisters is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It has a huge collection of medieval artworks. These artworks are shown inside buildings that look like parts of old French monasteries. The museum's main parts are four cloisters (covered walkways around an open courtyard). These cloisters—Cuxa, Saint-Guilhem, Bonnefont, and Trie-sur-Baïse—were brought from France before 1913 by an American sculptor named George Grey Barnard.

Later, a rich person named John D. Rockefeller Jr. bought Barnard's collection for the museum. Other important artworks came from the collections of J. P. Morgan and Joseph Brummer. The museum building was designed by Charles Collens. It sits on a steep hill and has different levels. Inside, you'll find medieval gardens, chapels, and themed rooms. These rooms include the Romanesque, Fuentidueña, Unicorn, Spanish, and Gothic rooms.

The museum's design makes you feel like you're in a medieval European monastery. It holds about 5,000 art pieces, all from Europe. Most of them date from the 12th to the 15th centuries. The collection includes stone and wood sculptures, tapestries, illuminated manuscripts (decorated books), and paintings. Famous pieces include the Mérode Altarpiece (around 1422) and The Unicorn Tapestries (around 1495–1505).

Rockefeller bought the land for the museum in 1930 and gave it to the Metropolitan Museum in 1931. When The Cloisters opened on May 10, 1938, people said it was a collection "shown informally in a picturesque setting, which stimulates imagination and creates a receptive mood for enjoyment."

Contents

History of The Cloisters

How the Museum Started

The idea for The Cloisters came from George Grey Barnard. He was an American sculptor who also collected medieval art. He created a medieval art museum near his home in Upper Manhattan. Barnard studied art in Paris and started buying and selling old European objects. He found many architectural pieces from old abbeys and churches in France.

Barnard was especially interested in buildings from the 12th century. Over time, many stones from these old buildings were reused by local people. Barnard was one of the first to see the value in these old pieces. By 1907, he had a high-quality collection. He even claimed to have found a tomb carving being used as a bridge over a stream! By 1914, he had enough items to open a gallery in Manhattan.

Rockefeller's Role

Barnard often had money problems. In 1925, he sold his collection to John D. Rockefeller Jr.. Rockefeller bought the collection for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These pieces became the main part of The Cloisters. Rockefeller and Barnard were very different people, but Rockefeller kept Barnard as an advisor.

In 1927, Rockefeller hired Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to design a park in the Fort Washington area. In 1930, Rockefeller offered to build The Cloisters for the Metropolitan Museum. He chose a site in Fort Tryon Park because of its great views and quiet location. The land and buildings were bought that year.

The Cloisters building and its gardens were designed by Charles Collens. He included parts from old abbeys in France and Spain. Pieces from places like Sant Miquel de Cuixà, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, and Bonnefont-en-Comminges were carefully taken apart. They were then shipped to New York City and rebuilt into the new museum. Construction took five years, starting in 1934. The museum officially opened on May 10, 1938.

Adding to the Collection

Rockefeller paid for many of the early artworks. He often bought items and then gave them to the museum. Another big donor was J. P. Morgan, who also gave many artworks to the Metropolitan.

Later, the art dealer Joseph Brummer became an important source of objects. After Brummer's death in 1947, the Cloisters' curator, James Rorimer, bought many items from his collection. These pieces, including works in gold, silver, and ivory, are now in the Treasury room at The Cloisters.

Art Collection Highlights

The museum has about 5,000 art pieces. They are shown in different rooms and spaces. The Cloisters doesn't just collect famous masterpieces. Instead, the objects are chosen to fit the medieval feel of each room. Many pieces, like carved stone, stained glass, and windows, are part of the buildings themselves.

Paintings and Sculptures

One of the most famous paintings is Robert Campin's Mérode Altarpiece (around 1425–28). This painting is very important for understanding early Dutch art. It has been at The Cloisters since 1956. Other paintings include a Nativity altarpiece and the Jumieges panels.

The 12th-century English ivory Cloisters Cross has over 92 detailed carvings. Another 12th-century French metal reliquary cross also has many engravings. Other notable pieces include a 13th-century English Enthroned Virgin and Child statue. There is also a German statue of Saint Barbara from around 1490.

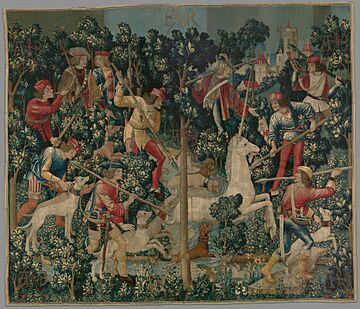

The museum also has many medieval frescoes (wall paintings), ivory statues, and metal shrines. It has rare Gothic boxwood miniatures (tiny carvings). Many objects have interesting stories. For example, the Unicorn tapestries were once used by the French army to cover potatoes! Rockefeller bought them in 1922 and gave them to the museum in 1938.

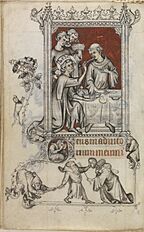

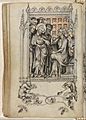

Illuminated Manuscripts

The museum has a small but amazing collection of illuminated books (hand-decorated books). These books are displayed in the Treasury room. They include the French "Cloisters Apocalypse" (around 1330) and Jean Pucelle's "Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux" (around 1324–28). Also, there's the "Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg" and the "Belles Heures du Duc de Berry" (around 1399–1416). In 2015, the Cloisters bought a small Dutch Book of Hours by Simon Bening.

The "Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux" is a tiny book with 209 pages. It has 25 full-page pictures and almost 700 border designs. It was made for Jeanne d'Évreux, the queen of France. The book uses gray drawings, which make the figures look like sculptures. It's considered a top example of Parisian court art from that time.

The "Belles Heures" is one of the most richly decorated books of its kind. It's the only complete book known to be made by the Limbourg brothers. Rockefeller bought it in 1954 and gave it to the Metropolitan Museum.

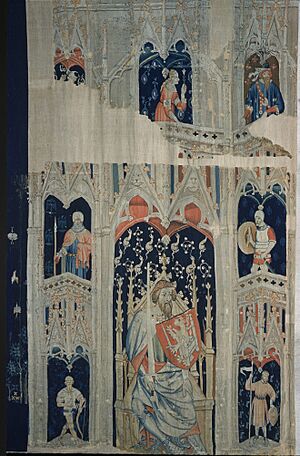

Tapestries

The museum has two special rooms for tapestries. These are the South Netherlandish Nine Heroes (around 1385) and the Flemish The Unicorn Tapestries (around 1500). The Nine Heroes tapestries are some of the oldest surviving examples. They show famous heroes like Hector, Alexander the Great, and King Arthur.

The Unicorn Tapestries room is entered through a door carved with unicorns. These tapestries are large and colorful, made in Paris and woven in Brussels or Liège. They were made for Anne of Brittany around 1495–1505. Rockefeller bought them in 1922 and gave them to the museum in 1937. They were cleaned in 1998 and are now displayed in their own room.

Stained Glass

The Cloisters has about 300 stained glass panels. Most are French and German, from the 13th to early 16th centuries. Many have bright colors and abstract designs. The largest collection is in the Boppard room, named after a church in Germany. These works show how light was used in Gothic art.

A curator named Jane Hayward helped the museum get more stained glass in the 1970s. She added windows from the Rhineland to the Campin room. This made the room feel more like a medieval home, matching the Mérode Altarpiece.

Museum Building and Gardens

The museum building is built into a steep hill. This means its rooms are on different levels. The outside of the building is mostly modern, but it uses ideas from a 13th-century church in France. The architect, Charles Collens, was inspired by Barnard's collection. Rockefeller was very involved in the building's design and construction.

The building includes parts from four French abbeys. These pieces were moved and rebuilt in New York between 1934 and 1939. The architects wanted the building to blend with the rocky hilltop. They also wanted it to have great views of the Hudson River. Construction of the outside began in 1935.

The Cloister Gardens

Cuxa Cloister

The Cuxa cloisters are the main part of the museum. They are on the south side of the main level. These cloisters originally came from the Benedictine Abbey of Sant Miquel de Cuixà in the Spanish Pyrenees. The monastery was abandoned in 1791. About half of its stone pieces were moved to New York between 1906 and 1907. The Cuxa cloisters opened to the public on April 1, 1926.

This square-shaped garden was once a central area where monks lived. The garden today has plants that would have been found in medieval times. The stone columns and carvings are original. They are made from pink marble from the Pyrenees. The carvings show leaves, pine cones, religious figures, and strange creatures. These creatures might represent nature or evil.

Saint-Guilhem Cloister

The Saint-Guilhem cloisters came from the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert. They date from the 800s to the 1660s. Barnard bought them around 1906. About 140 pieces, including columns and carvings, were moved to New York. The carvings show leaves and strange heads, like figures from the Presentation at the Temple and the Mouth of Hell.

The Guilhem cloisters are inside the museum's upper level. They are smaller than they were originally. The garden has a fountain and plants in fancy pots. A skylight covers the area, keeping it warm in winter.

Bonnefont Cloister

The Bonnefont cloisters were put together from several French monasteries. Most pieces come from a 12th-century Cistercian abbey at Bonnefont-en-Comminges. Barnard bought the stonework in 1937. Today, the Bonnefont cloisters have 21 double carvings. They surround a garden with medieval features, like a central wellhead and raised flower beds. The garden has a medlar tree, like those seen in The Unicorn Tapestries. This cloister is on the upper level and offers views of the Hudson River.

Trie Cloister

The Trie cloisters were made from two French buildings from the late 1400s to early 1500s. Most parts came from the Carmelite convent at Trie-sur-Baïse. The original abbey was destroyed in 1571. The rectangular garden has about 80 types of plants and a tall limestone fountain. Like the Saint-Guilhem cloisters, the Trie cloisters have modern roofs.

The convent at Trie-sur-Baïse had about 80 white marble carvings. Eighteen of these were moved to New York. They show scenes from the Bible and lives of saints. Some carvings show legendary figures like Saint George and the Dragon. The carvings are placed in order, starting with God creating the world.

Gardens Overview

The Cloisters has three gardens: the Judy Black Garden at the Cuxa Cloister, and the Bonnefont and Trie Cloisters gardens. They were planted in 1938. They have over 250 types of medieval plants, flowers, herbs, and trees. This makes them one of the most important collections of specialized gardens in the world. The gardens are cared for by experts who also study medieval gardening.

Inside the Museum

Gothic Chapel

The Gothic chapel is on the museum's ground level. It was built to show off its stained glass and large sculptures. The entrance has beautiful stained glass windows from France. The chapel has high, arched ceilings. The three central windows are from a church in Austria, around 1340. They show scenes like Martin of Tours. The glass on the east wall is from France, around 1325.

The chapel has three large sculptures by the main windows. Two are tall female saints from the 14th century. There is also a 13th-century Bishop from Burgundy. A large limestone sculpture of Saint Margaret is on the wall by the stairs. It dates to around 1330.

The chapel also has six beautiful tomb carvings. Three are from a monastery in Catalonia. One is the tomb of Jean d'Alluye, a knight from the crusades, from around 1248–67. He is shown as a young man in armor. Another is a lady from the mid-13th century, possibly Margaret of Gloucester. She is dressed in fancy aristocratic clothes.

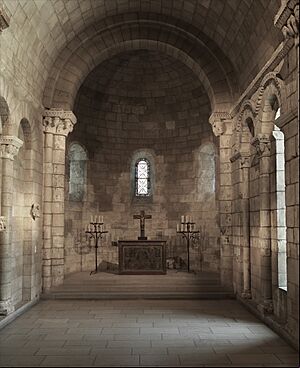

Fuentidueña Chapel

The Fuentidueña chapel is the museum's biggest room. Its main feature is the Fuentidueña Apse. This is a rounded Romanesque part of a church, built between 1175 and 1200 in Spain. By the 1800s, the church was in ruins. Rockefeller bought the chapel for The Cloisters in 1931. It took many years of talks between Spain and the US to make this happen.

The structure was taken apart into almost 3,300 stone blocks. Each block was carefully labeled and shipped to New York. It was rebuilt at The Cloisters in the late 1940s. The chapel opened to the public in 1961.

The apse has a wide arch and a half-dome ceiling. The carvings at the entrance show scenes like the Adoration of the Magi. Inside the dome is a large wall painting from a Spanish church, dating from 1130 to 1150. It shows Mary as the mother of God. A crucifix from Spain (around 1150–1200) hangs in the apse. The outside wall has small windows, designed to let in as much light as possible.

Langon Chapel

The Langon chapel is on the museum's ground level. Its right wall was built around 1126 for a Romanesque cathedral in France. The main part of the chapel came from a small Benedictine church built around 1115. When it was bought, it was in bad shape. About three-quarters of its original stonework was moved to New York.

You enter the chapel from the Romanesque hall through a large, fancy French Gothic stone doorway. This doorway was made for Moutiers-Saint-Jean Abbey in France. The abbey was damaged many times over the centuries. Barnard arranged for the doorway to be moved to New York. It was the main entrance of the abbey.

The carvings on the doorway show the Coronation of the Virgin. They also have statues of two kings and kneeling angels. The large figures on either side of the doorway are early Frankish kings, Clovis I and his son Chlothar I. Many of the statues are damaged, with most of their heads missing.

Romanesque Hall

The Romanesque hall has three large church doorways. The main visitor entrance is next to the Guilhem Cloister. A huge arched doorway from Moutier-Saint-Jean de Réôme in France dates to around 1150. It has carvings of animals and leaves. Two older doorways are from Reugny, Allier, and Poitou in central France.

The hall also has four large stone sculptures from the early 13th century. These show the Adoration of the Magi. There are also wall paintings of a lion and a wyvern from a monastery in Spain. On the left side of the room are portraits of kings and angels.

Treasury Room

The Treasury room opened in 1988 for the museum's 50th anniversary. It holds many small, valuable objects. Many of these came from the collection of Joseph Brummer. The room displays the museum's illuminated manuscripts, a French 13th-century silver arm-shaped reliquary, and a 15th-century deck of playing cards.

Museum Library

The Cloisters has one of the Metropolitan Museum's 13 libraries. It focuses on medieval art and architecture. It has over 15,000 books and journals. It also keeps the museum's old papers, records, and personal papers of George Grey Barnard. The library is mainly for museum staff, but researchers and students can visit by appointment.

New Acquisitions

The Cloisters often buys new artworks and rarely sells them. The museum tries to have a good mix of religious and everyday objects. It looks for pieces that show what medieval European life was like. In 2011, it bought The Falcon's Bath, a beautiful tapestry from around 1400–1415. It's one of the best-preserved tapestries of its kind. In 2015, the museum also bought a Book of Hours by Simon Bening.

Events and Programs

The museum's unique buildings and sounds make it a great place for music concerts and medieval plays. Past plays include The Miracle of Theophilus in 1942. Recent exhibitions include "Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures" in 2017.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: The Cloisters para niños

In Spanish: The Cloisters para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |