Seneca language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Seneca |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onödowáʼga꞉ʼ | ||||

| Native to | United States, Canada | |||

| Region | Western New York and the Six Nations Reserve, Ontario | |||

| Ethnicity | Seneca | |||

| Native speakers | 100 (2007)e18 | |||

| Language family | ||||

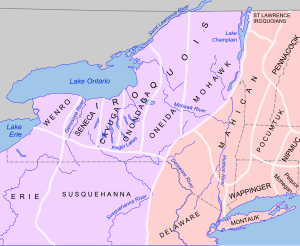

Map of the New York tribes before European arrival, showing the pre-contact distribution of Seneca in western New York Iroquoian tribes Algonquian tribes

|

||||

|

||||

Seneca (pronounced SEN-ih-kuh) is the language spoken by the Seneca people. They are one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois League. This language belongs to the Iroquoian language family. When Europeans first arrived, Seneca was spoken in western New York.

The name Seneca has been used since the 1600s, but its exact meaning is not clear. The Seneca people call their language Onödowáʼga꞉, which means "those of the big hill."

About 10,000 Seneca people live in the United States and Canada. Most live on reservations in western New York. Others live in Oklahoma and near Brantford, Ontario. Since 2013, there has been a strong effort to bring the language back to life.

Contents

What is the Seneca Language?

Seneca is an Iroquoian language. It is spoken by the Seneca people, who are part of the Iroquois Confederacy. This group was first known as the Five Nations, and later the Six Nations.

Seneca is most closely related to other languages from the Five Nations. These include Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk. Among these, Seneca is most similar to Cayuga.

The first records of the Seneca language come from the early 1700s. These were two dictionaries made by a French missionary named Julien Garnier. Over the 1700s, the way Seneca sounds changed a lot. Because of these changes, the Seneca spoken then would be very different from modern Seneca.

Today, Seneca is mainly spoken in western New York. It is used on three reservations: Allegany, Cattaraugus, and Tonawanda. It is also spoken in Ontario, on the Grand River Six Nations Reserve. There are only about 100 native speakers left. However, many people are working hard to teach and save the language.

How is Seneca Written and Spoken?

Seneca words are written using 13 letters. Three of these letters can have a special mark called an umlaut. The language also uses a colon (꞉) and an acute accent mark.

Seneca is usually written in all lowercase letters. Capital letters are used only rarely, usually for the first letter of a word. You will never see words written in all capital letters, even on road signs.

The vowels and consonants used are: a, ä, e, ë, i, o, ö, h, j, k, n, s, t, w, y, and the glottal stop (ʼ). Sometimes, t is written as d, and k as g. This is because Seneca does not have a clear difference between voiced and voiceless sounds for these letters. The letter j can also be written as tsy.

Seneca Sounds: Consonants

Here are the consonant sounds in Seneca:

| Dental and alveolar |

Postalveolar and palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | n | ||||

| Stop | Voiceless | t | k | ʔ ⟨ʼ⟩ | |

| Voiced | d | g | |||

| Affricate | Voiceless | t͡s ⟨ts⟩ | t͡ʃ ⟨č⟩ | ||

| Voiced | d͡z ⟨dz⟩ | d͡ʒ ⟨j⟩ | |||

| Fricative | s | ʃ ⟨š⟩ | h | ||

| Approximant | j ⟨y⟩ | w | |||

Seneca Sounds: Vowels

Seneca has several vowel sounds. Some are oral (air comes out of the mouth), and some are nasalized (air comes out of the nose and mouth).

Here are the vowel sounds:

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Close-mid | e | o |

| Open-mid | ɛ̃ ⟨ë⟩ | ɔ̃ ⟨ö⟩ |

| (Near)Open | æ ⟨ä⟩ | ɑ ⟨a⟩ |

Nasal vowels, like the ones in "sing" or "song," are written with two dots above them (⟨ë ö⟩). Long vowels have a colon (⟨:⟩) after them. Stress, or emphasis on a syllable, is shown with an acute accent mark (like ⟨é⟩).

How Seneca Words are Built

Seneca is a polysynthetic and agglutinative language. This means words are often very long and made by adding many small parts (called morphemes) together. It's like building with LEGOs, where each small piece adds a bit more meaning.

Most Seneca words are verbs (action words). Verbs can have many different parts added to them. This makes it possible to create a huge number of different Seneca verbs.

Building Verbs

A Seneca verb starts with a verb root, which is the main meaning of the word. Then, other parts can be added to it.

- Adding meaning: You can add suffixes (word endings) to change the verb's meaning. For example, one suffix means "while walking." Another can reverse the meaning, like adding "un-" to "tie" to make "untie."

- Middle Voice / Reflexive: These prefixes (word beginnings) show that the action is done by the agent and also affects the agent. For example, "he washes himself."

- Incorporating Nouns: You can even put a noun (a person, place, or thing) right into the verb! This noun often becomes the object of the verb. For example, you might have a verb that means "to eat" and add the noun for "apple" into it to make a single word meaning "to eat an apple."

Here are some examples of how suffixes can change a verb's meaning:

| Name | Form | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Ambulative | -hne- | "while walking" |

| Andative | -h- | Goes to a different place to do the action. |

| Archaic Causative | -hw- | "cause," "make" (less common) |

| New Causative | -ht- | "cause," "make" (more common) |

| Archaic Reversive | -hs- | Reverses meaning (e.g., "tie" > "untie") (less common) |

| New Reversive | -kw- | Reverses meaning (e.g., "tie" > "untie") (more common) |

| Benefactive | -ni-, -ne- | Action helps or harms someone (e.g., "for him/her") |

| Directive | -n- | Action happens towards a certain place (e.g., "go there") |

| Distributive | -hö- | Action affects things in many places or times. |

| Eventuative | -hsʼ- | "eventually" |

| Facilitative | -hsk- | "easily" |

| Inchoative | -ʼ- | "become," "get," "come to be" |

| Instrumental | -hkw- | "by means of" |

Aspect Suffixes

Every Seneca verb has an aspect suffix. This suffix tells you about the timing or state of the action. For example, it can show if an action is:

- Habitual: Happens regularly (like "I usually eat").

- Progressive: Happening right now (like "I am eating").

- Stative: Describes a state (like "it is heavy").

- Perfect: Completed action with a result (like "I have eaten").

There is also a punctual suffix for actions that happen at a single point in time.

Pronominal Prefixes

Seneca verbs also have very detailed pronominal prefixes. These prefixes are added to the beginning of the verb. They tell you not only who is doing the action (the agent) but also who is receiving the action (the patient).

For example, a single prefix can mean "I see you (singular)." There are 55 possible pronominal prefixes! They show if the agent or patient is singular, dual (two people), or plural (more than two). They also show if "we" includes the listener or not. For third-person (he, she, it, they), they even show gender (masculine or feminine/animal) and if something is alive or not.

Building Nouns

Building nouns in Seneca is much simpler than building verbs. Nouns have a main noun root and a noun suffix. They can also have a pronominal prefix at the beginning.

- Noun Suffix: This simply shows that the word is a noun.

- Locative Suffixes: These suffixes show location. For example, one suffix means "on" or "at" the noun, and another means "in" the noun.

- Pronominal Prefixes: For nouns, these prefixes show possession. So, instead of "I see," they mean "my" or "your."

How Seneca Sentences Work

In Seneca, a lot of information is packed into each word. Because of this, the order of words in a sentence is very flexible. There isn't a strict "subject-verb-object" rule like in English.

Instead, new or important information usually comes first in a Seneca sentence. If a speaker thinks a noun is more important than a verb, the noun might appear before the verb. If not, it usually comes after the verb.

Connecting Ideas: Conjunctions

Seneca uses different words to connect parts of a sentence, similar to "and," "or," or "but" in English.

Here are some ways Seneca connects ideas:

| Conjunction | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ø | 'and' | Used between two verb phrases. |

| koh | 'and' | Usually comes after the word it connects. |

| háéʼgwah or há꞉ʼgwah | 'also,' 'too' | Connects things of equal importance. |

| gi꞉h | 'or' | Usually placed between the two choices. |

| giʼsëh | 'maybe' | Usually comes at the end of the sentence. |

| giʼsëh ... giʼsëh | 'either ... or' | The first part is between choices, the second after both. |

| gwa꞉h heh | 'but' | Usually comes before the new idea it introduces. |

| sëʼëh | 'because' | Usually comes before the reason. |

Pointing Things Out: Deictic Pronouns

Seneca has words to point out things based on how close or far they are. This is like saying "this" or "that" in English.

Here are some examples:

| Pronoun | Meaning | Distance |

|---|---|---|

| në꞉gë꞉h | 'this' | Close by |

| në꞉dah | 'this one here' | |

| hi꞉gë꞉h | 'that' | Far away |

| né꞉neʼ | 'that one here' | |

| neʼhoh | 'that,' 'there' |

Bringing the Language Back to Life

Many people are working hard to save and teach the Seneca language.

- Seneca Faithkeepers School: In 1998, this school was started. It teaches children the Seneca language and traditions five days a week.

- Teacher Recognition: In 2010, Anne Tahamont, a K-5 Seneca language teacher, was recognized for her work. She helps students and works on documenting the language.

- Computer Catalog Project: In 2012, the Seneca Nation received a $200,000 grant. This money helps them work with the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). They are creating an easy-to-use computer catalog or web-based dictionary for the Seneca language. This will help future generations learn and speak it. Robbie Jimerson, an RIT student working on the project, said, "My grandfather has always said that a joke is funnier in Seneca than it is in English."

- Seneca Language App: As of January 2013, a Seneca language app was being developed.

- Mentorship and Newsletter: In fall 2012, Seneca language learners started working with fluent speakers. A newsletter, Gae꞉wanöhgeʼ! Seneca Language Newsletter, is also available online.

- Radio Station: The former Seneca-owned radio station WGWE used to broadcast a "Seneca Word of the Day." It also played some Seneca music and used the language in its shows. This helped more people learn about the language.

- Sports Announcing: In 2013, middle school students announced a lacrosse game in the Seneca language. This was the first public sports event to be announced in Seneca.

- Bilingual Road Signs: Since 2016, you can see bilingual road signs in the Seneca capital of Jimersontown. These signs, like stop signs and speed limit signs, are in both English and Seneca. Before this, signs for townships on the Allegany Indian Reservation were also put up in Seneca along Interstate 86.

Sample Texts

"Funny Story"

This story was translated by Nils M. Holmer.

hatinöhsutkyöʼ

They-had-a-house-it-is-said

yatatateʼ

they-are-grandfather-and-grandson

wayatuwethaʼkyöʼ.

they-went-hunting-it-is-said.

tyëkwahkyöʼshö

All-of-a-sudden-they-say

katyeʼ

it-flies

citeʼö

a-bird

hukwa

nearby

uswëʼtut

it-hollow-tree

katyeʼ

then-it-is-said

nekyöʼ

here

nehuh

it-went-into.

hösakayöʼ.

In-just-a-little-while

tatyöʼkyöʼshö

it-flies

katyeʼ

just-a-little-while

tötakayakëʼt.

it-flew-again.

tatyöʼkyöʼshö

In-just-a-little-while

skatyeʼ

it-flew-again

hösakayöʼ.

it-went-in.

tatyöʼshö

In-just-a-little-while

katyeʼ

it-flies

tötakayakëʼt.

it-came-out-again.

A grandfather and a grandson had a house, it is said; they went hunting. All of a sudden a bird came flying (from) near a hollow tree; then, it is said, it flew into it. After a little while it flew in again. After a little while, it flew back (into the hollow tree). After a while it came flying out again, etc.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |