September 1811 Chilean coup d'état facts for kids

The Revolution of September 4, 1811 was a military action in Chile. It is also known as the September 4 Coup or Carrera's First Coup. The main goal was to change the National Congress. They wanted it to support independence from Spain more strongly. The military leaders were the Carrera brothers, especially José Miguel Carrera. He later became a key figure in the period called Patria Vieja (1810-1814). On the political side, the Larraín family (also called Los Ochocientos) led the movement, with Fray Joaquín Larraín at the front.

The revolution quickly took control of Congress. Carrera, presenting demands from the people of Santiago, made the legislators agree to most requests. The main change was removing people who supported the King (called Saracens) or those who were neutral. They were replaced by people known for their patriotic ideas. This was the first of four coups led by Carrera. He also led coups on November 15 and December 2 of the same year, and on July 23, 1814. This event was also the first successful coup in the history of Chile.

Contents

How it Started

Carrera Comes Home

José Miguel Carrera returned to Chile on July 25, 1811. He had been fighting for the King of Spain against the French. He knew about the political changes happening in Chile. His father had been part of the first Government Junta. Carrera arrived in Valparaíso and then went to Santiago on July 26.

In Santiago, he found out about a planned revolution. His brother, Juan José Carrera, was leading it. The plan was to remove certain people from Congress.

That night, after the embrace of my family, I retired to sleep in the company of my brother Don Juan José, who somehow imposed on me the situation of my country. He told me that he was arriving at the time of a revolution that would take place at ten o'clock on the 28th. It was actually scheduled for the 27th. It was aimed at removing some individuals from Congress, Commander of Artillery Francisco Javier Reina, and I don't remember what other things. Those directing the work were Martínez de Rozas and Larraines, joined by Antonio Álvarez Jonte. It seemed to me that the project contained a great deal of ambition and decisions detrimental to the cause and to my brothers, who were the executors. I begged them to postpone that deadline until my return from Valparaíso, where I was to return so that Fleming could come to see the capital. He offered to do so and complied, in spite of the fact that in the morning many of those invited were present for the purpose.

Carrera went back to Valparaíso to meet Charles Elphinstone Fleming. When he returned to Santiago around August 11, Carrera learned more about the revolution plans. Patriots, called exalted, wanted the Carrera brothers to lead the military action. At first, José Miguel Carrera told his brothers to stay away from these plans. He wanted to understand why the patriots wanted such a big change.

I asked why and for what purpose such a resounding revolution was intended; I was told: The Congress and part of the troops are in the power of inept men and enemies of the cause. All the sane part of the people clamor to remedy this evil and it is not possible because there is no freedom; it is necessary to resort to the force commanded by the good patriots, which is the only hope that remains. We will all sacrifice our lives to save the motherland.

Trying to Stop the Revolution

Carrera first suggested gathering people and soldiers to ask for changes peacefully. But he was told the people were too scared. Then, Carrera suggested that the "healthy part of the people" should sign demands for Congress. He, with his soldiers, would support this plan.

Even with his promise, Carrera hesitated to start the coup. He felt he should try "all possible means to avoid a harmful step." He spoke to the president of the National Congress, Manuel Pérez de Cotapos. But Pérez refused to agree to the demands peacefully. José Miguel Carrera warned Pérez about his refusal.

You have compromised me; fear the results of such an imprudent step.

Congress Before September 4

The National Congress started on July 4, 1811. Most members either supported the King or did not care about the ongoing changes. This made it hard for the patriots, led by Juan Martínez de Rozas. They often argued with their opponents. The first big fight was about changing the number of deputies for Santiago from 6 to 12. This helped the royalists.

Patriot Wins and Losses in Congress

Even though they were a minority, the patriots in Congress tried to stop royalist plans. After a failed military plan on July 27, the patriots focused on stopping the election of a new executive board. They knew they would lose again.

A big win for the patriots was stopping funds from being sent to Spain. These funds were for Spain's war against Napoleon. However, they lost when Congress rejected Manuel de Salas's idea to divide the territory. This plan would have given Coquimbo the same status as Santiago and Concepción. This would have helped Rozas gain more power in the area. After this rejection, 12 patriot deputies left Congress on August 9. They complained about Santiago having 12 deputies instead of 6.

Rozas Steps Back

Many historians see the political situation in Chile around 1810-1811 as a fight between supporters and opponents of Juan Martínez de Rozas. Rozas wanted a strong government. His group would later join Bernardo O'Higgins's government. Opposing them were those who wanted more public involvement and less government power.

However, Rozas was not popular with Santiago's rich families. They questioned his actions, like the Scorpion scandal. They also disliked his close ties with Álvarez Jonte and his role in the Figueroa mutiny. In the Congress elections, Rozas's side lost badly in Santiago. This was made worse by Santiago having 12 representatives instead of 6. This led to many complaints from the pro-independence group. This group was now led by the Larraínes (Ochocientos), who had taken over from the defeated Martínez de Rozas.

Martínez de Rozas lost even more support after his failed military plan on July 27. Only a few people showed up, and Juan José Carrera and his soldiers were absent. Seeing no other options, the most radical deputies left Congress on August 9. With the revolution changing course, Martínez de Rozas went south to Concepción. He planned a revolution there for September 5. He did not know about the events that had already happened in Santiago on September 4, led by the Carrera brothers.

The Military Coup

Taking the Artillery Barracks

On Wednesday, September 4, just before noon, José Miguel Carrera arrived at the Plazuela de la Moneda. He was riding a horse and dressed as a sergeant major. He planned to carry out a detailed plan with his brothers and supporters. However, things did not go exactly as planned. According to Friar Melchor Martinez, it started earlier, at 6 a.m.:

On the 4th, from 6 o'clock in the morning, seventy Grenadiers entered in parade and in disguise at the house of Carrera, where a plentiful lunch and plenty to drink were served, after which diligence the object of their meeting was discovered, offering them great prizes if they would force and seize the Artillery park; inflaming them with the false species that this corps, united with the four quartered companies of the Regiment of the King, had prepared to assault the Grenadier barracks and put them all to the sword.

Around noon, José Miguel Carrera arrived with his brothers outside the artillery barracks. His fancy uniform and horse caught the eye of all the sentries. The guards gathered to watch Carrera's horse tricks, ignoring the barracks. At that moment, the Carrera brothers started a "joking conversation" with the officer in charge. They asked him for a recommendation letter to send horses to a brother's farm. The officer said he had no inkwell, but the Carreras kept asking. He finally agreed to go write it in a nearby room. As soon as the officer entered, artillery captain Luis Carrera locked the door. He and other officers stood in front of the weapons with their swords drawn. This stopped any soldier from grabbing a rifle.

Just then, the clock struck twelve. As planned, seventy men from the grenadier battalion came out of their hiding place. This was at the house of Ignacio de la Carrera, right behind the barracks. At the same time, artillery sergeant Ramón Picarte, who was part of the plan, suddenly took the weapon from the sentry at the barracks door. The sergeant on duty, Juan Gonzalez, shouted "Treason!" but Juan Jose Carrera shot him dead. The guards were helpless. The Carrera family quickly took the artillery barracks. In minutes, groups of grenadiers gathered there and formed under the Carrera family's orders. José Miguel Carrera immediately sent Juan J. Zorrilla with 12 men to arrest Commander Reina. This prevented him from stopping the revolution.

The Political Coup

Demands to Congress

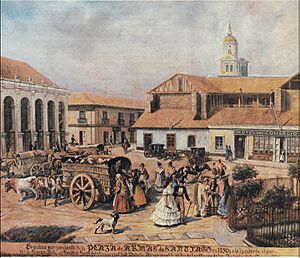

After taking the artillery barracks, José Miguel Carrera organized his soldiers. He took four cannons from the barracks and marched to the main square (today's Plaza de Armas). Congress had been meeting as usual that morning, unaware of what was happening. But shouts of "Revolution! Revolution!" were soon heard in the square. The grenadier officers guarding Congress doors, who were working with the Carrera family, closed the doors. This stopped any legislator from leaving.

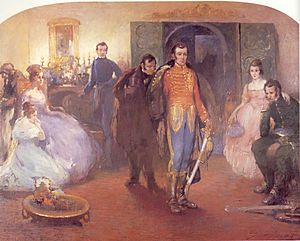

José Miguel Carrera's troops arrived and met no resistance. Even the militias protecting the congressmen put down their weapons. They were sent home by the rebels. Congressmen and people gathered in the square. According to chronicler Manuel Antonio Talavera, it was "a mob of between 25 to 30 factious" people. José Miguel Carrera got off his horse and entered Congress. He demanded that the congressmen listen to the people. The president of the corporation asked him to join him to hear the demands. Carrera wrote about some interesting moments in his Diary:

When I appeared in the hall of Congress after agreeing to the intimation, they begged me (particularly the President Don Juan Zerdán) to stay in their company to avoid insults and so that I could understand the people; I agreed. Soon after, some of the deputies, who were in a hurry to eat, said: "Let us hear once and for all what the people want. Don José Miguel Carrera can demand that they make their requests in writing to avoid confusion".

When Carrera went back to the square, he told the crowd that Congress would listen. Fray Joaquín Larraín, Carlos Correa, Francisco Ramírez, and some patriot deputies who had left on August 9 arrived. They gave Carrera a paper with the people's demands. These were the demands the Larraínes had prepared. Carrera checked the demands with the crowd. He noted that "for some unhappy people for whom everything was the same, each one of the petitions was given a viva." The demands Carrera later forced Congress to accept were:

.

- That the number of deputies from Santiago be reduced to seven, and that of the province of Concepción, which had more, to two, leaving the rest of the provinces with one representative.

- That the deputies of Santiago, Infante, Portales, Ovalle, Díaz Muñoz, Chaparro, Tocornal and Goycolea be separated; and to complete the seven that were to remain, Larraín and Correa.

- That the deputy of Osorno, Fernández, be separated.

- That the current Vocales del Poder Ejecutivo be removed, and five be named, which were Encalada, Rosales, Rozas (and due to his absence Benavente), Mackenna and Marín, Secretaries Vial and Argomedo.

- That no friar could be a deputy, nor be elected, or admitted to this position, subjects who are not of proven adherence to the system.

- That the Fiscal Agent Sanchez, and the City Attorney Rodriguez; the Aldermen Cruz and Mata, and the Government Clerk Borquez be separated from their jobs.

- Don Manuel Fernández will be confined to Combarbalá, Don Domingo Díaz Muñoz and Don Juan Antonio Ovalle to their estates, for six years; and if any plot or infraction is understood, they will be put to the sword as traitors to the King and the homeland. Don Antonio Mata to his farm and Don Juan Manuel Cruz to Tucapel, Infante to Melipilla.

- That Don Ignacio Carrera be named Brigadier.

- That the Corps of Patriots that had been discussed in the first meeting be formed.

- That Don Francisco Lastra be named Governor of Valparaíso in the vacancy of Don Juan Mackenna, who was removed for Vocal de la junta.

Carrera Leaves, Debate Continues

The demands caused arguments in Congress. Many realized the political trouble this would cause. It was hard for royalist and moderate members to accept such big changes. Some, like Juan Egaña, saw that the rebels were using the people as an excuse. Others argued that only Congress truly represented the people and tried to defend their rights. But Martínez explains how the congressmen went from defending their rights to fearing for their lives:

After reading the popular writing, it was seen that it contained 13 articles or petitions of difficult execution, in such an anguish of time and several views and opinions were raised, which observed by the seditious ones from the antechamber, they entered a second time with the former Mercedarian Larrain, Don Carlos Correa, Don Gregorio Argomedo, and Commissioner Carrera, and with imperious voices they urged the Congress to omit discussions and doubts in what the people were requesting, and to promptly sanction it to the letter, with the understanding that they were not allowed freedom to leave the room without the complete granting of all that was requested.

The grenadier battalion's pressure on Congress created fear. Carrera calmed them by promising their safety if the demands were accepted. Later, Carrera, tired of being the go-between, left the room. He left Larraín and Correa to finish making the demands official. By three in the afternoon, they announced the creation of an Executive Board. Its members were Juan Enrique Rosales, Juan Martínez de Rozas, Martín Calvo Encalada, Juan Mackenna, and Gaspar Marín. The discussions about the proposals continued until 11 at night. This ended a day of unexpected events that changed the course of the independence revolution.

The Rozas Revolution in Concepción

Rozas had left Santiago on August 13. He saw that the moderate and royalist deputies were too strong. He arrived in Concepcion on August 25 and was welcomed by friends. He quickly started his plan to expose the Congress's unfairness. He focused on the appointment of the twelve deputies for Santiago. He also highlighted how little attention was paid to the deputies from Concepción. When Rozas announced that the twelve patriot deputies had left Congress, Fray Antonio Orihuela spoke out. He said Santiago's rich families wanted to keep people enslaved. His words deeply affected the patriots of Concepción. They asked the Governor to call an open Cabildo (town hall meeting). This meeting happened on September 5. They did not know about the events in Santiago the day before. In this Cabildo, Concepción's representatives lost their power for allowing the twelve Santiago deputies. New representatives were elected, including Fray Orihuela, a strong patriot.

Concepción also asked nearby areas not to recognize Santiago. They urged them to join their cause. They also promoted local boards to check on their deputies' actions. For example, in Los Angeles, instead of removing their representative, the people praised and re-elected the patriot deputy Bernardo O'Higgins.

On September 16, news of this meeting reached Santiago. It caused fear of a split in the country. However, when the reasons for the southern revolution became clear, people realized both movements had the same goals. The fears disappeared. The deputies from Concepción were welcomed. Fray Antonio Orihuela helped make peace with the new Congress. In this way, the patriot movement, working separately, had struck two strong blows against the existing power in Congress. Melchor Martínez described the royalists' feelings after learning about Concepción. They saw the complete triumph of the patriotic cause:

A simple reading of the foregoing writing clearly demonstrates the aims and means of the whole spirit of innovation that animated the factious, removing the hypocritical veil of adherence to Ferdinand the Seventh and other disguises, with which they foolishly and perfidiously cover their projects and trade papers.

What Changed After the Revolution

The Rise of the Caudillo

A big change from the September 4 Revolution was the rise of a new type of leader: the caudillo. This was a leader supported by the military. Even with the progress made during Carrera's government, military power became the main way to gain power. Other political groups became less important. Carrera's own words show this idea of military power being more important than politics:

Fray Joaquín invited me for a walk in the company of Juan Enrique Rosales, Ramírez, Izquierdo and Pérez. On the way, after a few bottles of punch, Fray Joaquín said: "We have all the presidencies at home: me, President of Congress; my brother-in-law, of the Executive; my nephew, of the Audience; what more could we want?”. I was uncomfortable with his pride, and I unwisely wanted to answer him by asking him who had the presidency of the bayonets. This joke made such a strong impression on him that he demurred, and that night my boldness was criticized in the family, and many of them dictated the precautionary measures to be taken with the Carreras, particularly with me.

The Larraín Family's Power

Another result of this movement was the Larraín family's increased power. Carrera himself admitted they planned the military uprising. They put people in and out of Congress using the Carrera family's help. This was partly because the Larraínes were better at politics. Over time, José Miguel Carrera became angry with the Larraínes' power. He realized their true goals were their own ambitions. Despite the Larraínes' constant rejections of Carrera, the idea of using military force had worked. This pushed Carrera to get rid of the Larraínes. At the first chance, he led another coup. This time, he and his brothers took control, not "the Ottomans." The arguments between the Carrera and Larraín families became so bad that Carrera later sent Fray Joaquín Larraín into exile in Petorca. Carrera's diary shows his dislike for Fray Larraín.

See also

In Spanish: Primer golpe de Estado de José Miguel Carrera para niños

In Spanish: Primer golpe de Estado de José Miguel Carrera para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |