First Chilean National Congress facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First Chilean National Congress |

|

|---|---|

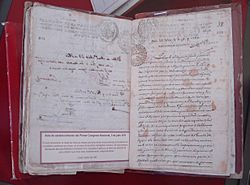

Inaugural session of the Congress

|

|

|

|

| Chambers | Unicameralism |

| History | |

| Founded | Palacio de la Real Audiencia de Santiago |

| Disbanded | December 2, 1811 |

| Preceded by | Without Legislative Body |

| Succeeded by | 1812 Senate, Chile |

| Leadership | |

|

President

|

Joaquín Echeverría Larraín

Juan Pablo Fretes |

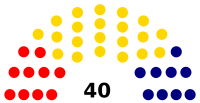

| Seats | 40 deputies (owners) |

|

|

|

Political groups

|

Royalist Indifferent party Patriot party |

The First Chilean National Congress was the very first group of lawmakers in Chile. It started on July 4, 1811, making it one of the oldest congresses in Latin America. Its main job was to decide how the Kingdom of Chile should be governed. This was important because King Ferdinand VII was held captive by Napoleon at the time. The Congress met from July 4 until December 2, 1811. It was then ended by a coup d'état (a sudden takeover of government) led by General José Miguel Carrera.

At first, the Congress was quite moderate. But after a takeover on September 4, 1811, the more radical "patriotic" group gained control. This group brought in many changes. For example, they passed a law called "freedom of womb." This law meant that children born to enslaved parents would be free. They also started planning for future changes, like laws about cemeteries and education. They even began writing a constitution, but the Congress closed before it could be finished.

Contents

Why the First Congress Was Called

The idea for this Congress came from the First Government Board. This board was set up on September 18, 1810. However, only people from Santiago had chosen this board. So, it was seen as a temporary government. Its goal was to rule only "until representatives from all parts of Chile could gather to form a new government."

Some towns held elections even before the board sent instructions. For example, in Petorca, a local leader named Manuel de la Vega had himself elected. In Concepción, Andrés del Alcázar was chosen. These early elections were later accepted if they followed the rules.

Many patriots, like Bernardo O'Higgins, doubted how well the Congress would work. They felt Chile lacked political experience. O'Higgins wrote:

As for me, I have no doubt that the first congress of Chile will show the most childish ignorance and will be guilty of all sorts of follies. Such consequences are inevitable, because of our total lack of knowledge and experience; and we cannot expect it to be otherwise until we begin to learn.

The board discussed calling the Congress for a long time. There was a lot of resistance. Finally, on December 15, thanks to Juan Martínez de Rozas, the board approved the rules for calling the First Chilean National Congress. These rules were similar to those used in Spain.

The Congress's main tasks were:

- To decide the best government system for Chile while the King was away.

- To set rules for different authorities and define their powers.

- To ensure the country's safety and help its people thrive.

Forty-two main representatives, called deputies, were to be elected. Each deputy also had a backup. Voting was done secretly. People who could be elected were natural-born Chileans or residents over 25. They needed to be respected and have good reputations. Priests, military officers, and those who had taken bribes could not be elected.

Local councils, called cabildos, were in charge of the elections. They chose who could vote and checked the results. People who could vote were respected individuals over 25, including priests and military personnel. Some, like José Miguel Infante, believed everyone should vote. But this idea did not become law.

Santiago's council felt their city, being the capital, should have more representatives. They asked to double their number from 6 to 12, and this was approved.

The Elections

Many people were unsure about the elections. Chileans were used to laws from the King. It was hard for them to imagine a group of Chileans making their own laws. To encourage voting, the Santiago council sought help from the church. The bishop of Santiago, Domingo Errázuriz, supported the elections. However, most church members were not interested in the revolution.

As elections happened in the provinces, different groups emerged:

- Radicals or Exalted: Led by Juan Martínez de Rozas, they wanted more independence.

- Moderates: This group, including Agustín Eyzaguirre, was less extreme. They often spoke through the Santiago council.

- Royalists: This group, strong in the Royal Audience, wanted to stay loyal to the Spanish King.

Elections were not always fair. Families tried to influence votes, and government officials sometimes interfered. Voting usually involved a solemn church service, then electors casting secret ballots in the council hall.

For Santiago's election, set for April 1, the radical group feared their opponents would win. They asked the board to exclude 34 people known to be against the revolution. The council agreed and even excluded more.

Figueroa's Mutiny

On April 1, the day of Santiago's elections, a military uprising happened. Lieutenant Colonel Juan Miguel Benavente was ordered to keep order. But his soldiers began to rebel, asking who they were fighting for. They only agreed to move when told it was for King Ferdinand VII. A corporal, Eduardo Molina, declared they only recognized Tomás de Figueroa as their leader. He called for the overthrow of the government board.

Captain Figueroa soon appeared and led the mutiny. He marched his group to the consulate square, expecting to find the board members. But the square was empty. Confused, they went to the main square. Figueroa entered the Royal Audience building, but the court refused to give him orders without consulting the board.

The board members, including Rozas and Carrera, quickly met. They ordered Commander Vial to confront the mutineers. After some confusion, Vial's loyal troops faced Figueroa's men. A shot was fired, and Vial's men responded with cannon fire. This caused chaos, leaving 20 wounded and 10 dead, including Corporal Molina. Figueroa fled, shouting, "I am lost, I have been tricked."

Martínez de Rozas helped capture Figueroa, who had hidden in a convent. Figueroa was put on trial and confessed. The board sentenced him to death for treason. He was shot and his body displayed.

After this mutiny, the board became stricter. They dissolved the Royal Audience and expelled many residents, including the former governor García Carrasco.

Elections in Santiago

By April 30, elected deputies from other provinces were in Santiago. They demanded to join the government, arguing they represented their towns. Some board members disagreed, as Santiago's elections hadn't happened yet. But Rozas, who had many supporters among these deputies, backed their request. The Santiago council protested, but their arguments were ignored. The government board now had 28 members, with Rozas and his supporters in charge.

The moderate group wanted to regain control. They pushed for Santiago's elections to happen quickly, setting them for May 6. On that day, voting tables were set up at the Palace of the Governors. Voters filled out lists with names for deputies. As voting was ending, Rozas, seeing his party might lose, demanded that military officers be allowed to vote. The council agreed to this, but paused voting until 4 PM. During this break, the moderates convinced the officers to support them. Their victory was confirmed when results were announced.

The election results were celebrated with great joy. On May 9, a special church service was held, with a military parade and cannon salutes. The newly elected deputies then joined the executive group that governed Chile until the Congress officially began.

Starting the National Congress

The Congress officially opened on July 4. Its meetings were held in the former rooms of the Royal Audience. On opening day, a procession of deputies, board members, and other important people walked to the cathedral. Inside the church, Father Camilo Henríquez gave a patriotic speech. He spoke about Spain's troubles and the need for Chile to defend itself. He argued that Chileans had the right to create their own constitution to ensure freedom and prevent tyranny.

Father Henríquez explained his ideas in three points:

First proposition: The principles of the Catholic religion, relative to politics, authorize the National Congress of Chile to form itself a Constitution.

Second proposition: There exist in the Chilean nation rights by virtue of which the body of its representatives can establish a Constitution and dictate providences that assure its liberty and happiness.

Third proposition: There are reciprocal duties between the individuals of the State of Chile and those of its National Congress, without the observance of which freedom and public happiness cannot be achieved. The former are bound to obedience; the latter to love of country, which inspires the right and all social virtues. The proof of these propositions is the argument of this speech.

After the speech, the deputies took an oath. They swore to defend the Catholic religion, obey King Ferdinand VII, and protect Chile from enemies. They all replied, "Yes, we swear."

After the church service, the deputies went to the Congress hall. Juan Martínez de Rozas gave the opening speech. He reminded everyone of their important duties. He stressed the need for laws based on Chile's real conditions, not just theories. These laws, he said, would protect against chaos and tyranny.

Then, the members of the old government board gave up their power. The Congress was now fully in charge. Juan Antonio Ovalle, as the oldest deputy, became the first president. He also gave a speech, and then the first session ended.

That night, the city celebrated with lights and fireworks.

The Congress had 36 main deputies and 36 backup deputies, representing their towns. On July 5, they set rules for the presidency, which would last 15 days. Juan Antonio Ovalle was elected president, and Martín Calvo Encalada vice president. On the same day, military leaders and other officials swore loyalty.

Congress's Work Before the September 4 Coup

The first meetings of Congress focused on setting up its administration. They chose two church members, Diego Antonio Elizondo and José Francisco Echaurren, as secretaries.

From July 8, they discussed creating an executive board and defining its powers. This caused a big debate. The radical deputies, who were a minority, opposed it. They knew the board would be controlled by the majority in Congress. They tried to argue about Santiago having 12 deputies instead of 6, but their efforts failed.

Many rumors and mocking writings were spread to criticize both sides. The moderate majority wanted to stop these writings and punish their authors. The radical minority argued that in a representative government, citizens should be free to express their opinions. The majority eventually dropped their plan.

After 15 days, new leaders were chosen for Congress. The moderates elected Martín Calvo Encalada as president and Agustín Urrejola, an enemy of the new system, as vice president. This angered the Rozas group. They planned to remove the most conservative deputies from Congress. Their goal was to make the radical group the majority, so Rozas could lead the executive board. This plan, set for July 27, failed.

The government did little to punish those involved. They only increased security. On July 29, it was decided the executive board would have three members with equal power, rotating the presidency. But the minority prevented an election.

On July 25, a British warship arrived in Valparaíso. On board was José Miguel Carrera, who would later play a big role. The ship also carried news from Spain, confirming the war against Napoleon. The ship's captain, Charles Fleming, was there to collect elected deputies for Spain and money for the war. He didn't understand Chile's new government.

Captain Fleming asked Congress for funds, citing the alliance between Spain and England. The radical group in Congress managed to avoid giving money. They responded vaguely and invited him to Santiago, which he refused. Fleming kept asking for the funds. Some in Congress wanted to cooperate, but the radicals strongly opposed it. Bernardo O'Higgins passionately declared that they would use their energy and courage to stop the money from leaving, as it was vital for Chile's defense.

On August 6, Congress gave its final answer:

The lack of foresight with which the leaders of the former Government lavished the Royal Treasury on luxurious buildings and other objects of minor importance, brought it into our hands weakened in such a way that it has been necessary to use the meager funds available to pay for a foot army, not only indispensable to defend the kingdom from the armed force of the usurper, but also, and very principally, from his machinations and intrigues aimed at revolutionizing these dominions, whose security is entrusted to us to maintain our unfortunate Sovereign; consequently, and in spite of the best wishes, we have not at this day any wealth to send.

After this, Fleming left Chile.

The executive board's organization was still undecided. On August 7, a rumor spread that Captain Fleming had landed in Valparaíso and arrested the governor. The radicals used this news to push for the board's immediate creation, with Rozas as president. The majority in Congress, though scared, didn't give in. They checked the news and found it was false.

The next day, discussions continued. Most deputies agreed on the powers of Congress and the board. Manuel de Salas suggested that Coquimbo should have equal representation, hoping Rozas would get a position. The majority rejected this. On August 9, seeing they would lose, twelve radical deputies walked out. They protested the increased number of Santiago deputies, calling it "outrageous."

The majority was surprised but didn't try to make peace. On August 10, the remaining Congress members met and appointed the board members: Martín Calvo Encalada, Juan José Aldunate, and Francisco Javier del Solar.

Congress called for new elections, allowing the withdrawn deputies to be re-elected. However, they suggested choosing other people for the country's safety. This caused conflicts in some towns. Some radicals, like O'Higgins, got their powers back. Rozas left for Concepción with his supporters, hoping to stir up support for freedom in the southern provinces.

On September 2, Congress set rules for its meetings. It had 15 articles. Key points included the president leading debates and proposing topics a day in advance. For serious matters, two expert deputies would inform their colleagues. Deputies had to speak calmly and in order. Voting would happen the day after discussions. Opinions could be public if Congress agreed.

José Miguel Carrera's First Coup d'État

José Miguel Carrera arrived in Chile on the Standard ship. He quickly went to Santiago and met his family, who were involved in the revolution. His brothers told him about the political situation. His brother Juan José tried to get him to join a planned takeover on July 28, but José Miguel wanted to delay it. This first attempt failed.

On August 12, Carrera returned to Santiago. He met with radical party supporters. They told him that most of Congress was made up of people against the revolution. Carrera joined their cause. He tried to influence the Congress president, Manuel Pérez de Cotapos, to change the government's direction. Carrera and his brothers then planned a coup for September 4.

On Wednesday, September 4, the coup happened. Not everything went as planned. Only 60 Grenadiers followed Juan José, who took the artillery barracks. This action resulted in one dead and one wounded.

Quickly, messages were sent to other barracks for more troops. Officer Zorrilla arrested Commander Francisco Javier Reina at his home.

José Miguel Carrera, on horseback, led a group of soldiers to the main square. Congress members and the executive board were working normally until they heard shouts of "Revolution!" Soldiers blocked the doors to prevent deputies from escaping. Carrera arrived and read a document. He presented his group's demands as "petitions of the people" and asked for a quick decision.

The petitions included:

- Reducing the number of deputies from Santiago to seven, and from Concepción to two. Other provinces would have one.

- Removing certain deputies from Santiago and Osorno.

- Replacing the current executive board with five new members.

- Forbidding friars from being deputies and ensuring only loyal people were elected.

- Removing several officials from their jobs.

- Exiling some individuals to their estates for six years, with a death threat if they plotted.

- Naming Ignacio Carrera as Brigadier.

- Forming a "Corps of Patriots."

- Naming Francisco Lastra as Governor of Valparaíso.

The soldiers' presence scared the deputies. After much debate, most of the demands were accepted. A new executive board was formed with Juan Enrique Rosales, Juan Martínez de Rozas, Martín Calvo Encalada, Juan Mackenna, and Gaspar Marín. This gave the patriotic group more power in Congress.

The Era of Reforms

The patriotic deputies gained more power in Congress. This was because some reactionary deputies were expelled, and provinces re-elected deputies who had left Congress. Some areas, like La Serena, even removed deputies who opposed the new movement. The moderates in parliament accepted the changes and didn't resist much.

On September 20, Joaquín Larraín was elected president of Congress, and Manuel Antonio Recabaren became vice-president. Both were patriots who had supported Carrera's coup. Congress, which had met in private, decided to open its doors to the public.

Government Changes

Congress created the province of Coquimbo and appointed Tomas O'Higgins as its governor.

On October 25, a plan for public safety and police was proposed. It suggested creating an official who would report directly to the government. This plan was approved later, in April 1813.

Congress also wanted to count all the people in the country (a census). They noted that towns were not well represented because there was no accurate population count. On October 9, they agreed to conduct a census. Priests were asked to help by listing their church members.

On September 23, Congress asked the council to stop selling positions like alderman. On October 11, they officially ended the practice of auctioning alderman positions in Santiago. For the time being, Congress would appoint people to fill vacant spots.

In legal matters, Congress made sure that lay judges (non-lawyers) had to work with a lawyer. They also created a special court for important cases, which acted as a final court of appeal.

They tried to set up "Courts of Settlement" to help people resolve disputes before going to court. But this idea didn't gain enough support.

The main reason for calling Congress was to write a constitution. This discussion was often delayed. Finally, on November 13, just before Carrera's second coup, a group was chosen to write a draft constitution. This draft was meant to govern Chile while the King was captive. Juan Egaña later wrote a draft constitution, but it was never used.

Church Reforms

Congress began some reforms related to the church. They claimed the right to appoint church officials. They also stopped collecting "parochial rights," which were fees for church services like baptisms and burials. These fees had become a heavy burden, causing some people to avoid church services.

Congress also started separating Chile from the Holy Office. They stopped sending money to Lima for it and decided to use that money for good causes within Chile. Seeing that convents for nuns had too much wealth, Congress decided on October 18 that nuns' dowries (money paid to join a convent) would go to their families when they died, except for Capuchin nuns.

Contributions for building churches were also stopped to save money for the government. Fees for religious bulls (official church documents) were abolished. A payment that monks had to make to their superior when leaving the monastery was also removed.

These church reforms often led to opposition from religious leaders. They sometimes attacked politicians in their sermons.

Cemetery Law

Congressman Bernardo O'Higgins proposed a law about cemeteries. He wanted to stop the practice of burying people inside or near churches. His father, Governor Ambrosio O'Higgins, had tried this before but faced resistance from the clergy. Congress supported the idea, and some church members like Juan Pablo Fretes also agreed. Congress decided to build a public cemetery in Santiago, placed away from the city to prevent disease.

A group was formed to plan the cemetery. But before the law could be fully carried out, Carrera's November coup ended the Congress's power. It was Bernardo O'Higgins himself, later as supreme director, who would finally make the cemetery a reality.

Money Matters

One of Congress's biggest worries was managing public money, which was in bad shape. They tried to avoid raising taxes, as this would make people dislike the government. Instead, they focused on cutting expenses.

They removed some tax exemptions that had been granted by the King. They also raised postal rates, but this didn't have a big effect because there wasn't much mail.

To cut costs, they targeted opponents of the government and officials from the old system. For example, Judas Tadeo Reyes had his salary cut to one-third. Congress asked to be informed of all vacant jobs to decide if they should be eliminated or if their salaries should be reduced. They decided no salary should be more than two thousand pesos a year (except for high-ranking military officers and governors). The office that managed Jesuit properties was closed, and its funds went to the national treasury.

Export duties (taxes on goods leaving the country) were abolished and replaced with a smaller tax on wheat exports. They encouraged growing guillipatagua instead of yerba mate, which was no longer coming from Paraguay. They also allowed temporary freedom for tobacco farming, but kept the tobacco tax.

Military Defense

In terms of defense, a new "Battalion of Patriots" was created. People could volunteer, but not all spots were filled. Only 8 battalions were formed. Congress began removing army commanders who seemed disloyal to the new government. The "Battalion of Commerce," made up of wealthy European merchants, was also disbanded because they were seen as suspicious.

To get weapons, they tried to negotiate with Buenos Aires, who promised to sell arms when they received them from Europe. When this didn't work, Congress decided on October 8 to buy weapons from private citizens and register all existing weapons. They also tried to set up a weapons factory in Chile, but this failed due to a lack of experts and materials. On the same day, they created the position of "inspector of troops" to oversee weapons care.

Foreign Relations

The diplomatic agent in Buenos Aires, Antonio Álvarez, was fired. He was accused of sending negative reports about Chile and spreading anti-Congress pamphlets. He was dismissed on September 26.

To strengthen ties with other governments and get news from Spain, Congress appointed Francisco Antonio Pinto as a representative to the Board of Buenos Aires on the 9th.

With Peru, on October 9, a secret agent was sent. Peru was seen as a threat because of the attitude of its viceroy, Abascal. The agent's job was to get "exact, prompt and reliable news" about what was happening in Peru.

The viceroy found out about this and demanded an official report on what had happened in Chile since the first government board was set up. Manuel de Salas wrote a response, explaining the events and trying to show that Chile was still loyal to the King.

Education

Congress planned big changes for education. On October 5, they gave the government board information needed to reform public schools. On October 7, they asked the head of the University of San Felipe for a report on the university's situation and how to improve it.

Two officials were asked to observe students in primary schools supported by the council. The experiment seemed successful. Deputies then encouraged other teachers to show similar results from their students.

Congress decided to close a school for native people in Chillán, which cost two thousand pesos. Instead, they proposed that native students be admitted to state schools and receive the same benefits. This was to help them "forget the shocking distinction that keeps them in the unjust dejection and hatred towards a people of which they should be a part."

Juan Egaña, before becoming a deputy, proposed a plan on October 24. He suggested creating a large school for students from Santiago and other regions. It would be led by the best teachers and include sciences, which were not widely taught then. Congress approved the plan and decided to share it.

Another detailed plan came from Camilo Henríquez. He proposed organizing education into three parts: physical sciences and mathematics, moral sciences, and languages and literature. Congress heard these plans and added them to other ideas for renewing studies.

Freedom of the Womb

The most important project during this time was the "freedom of wombs" law, pushed by Manuel de Salas. This law stated that all people born in Chile were free, no matter if their parents were enslaved. It also banned bringing enslaved people into the country. If enslaved people passed through Chile and stayed for more than six months, they would become free. Slavery was not as important in Chile's economy as in other Spanish American countries. Many patriots even freed their own enslaved people to help end slavery completely. Despite its good intentions, the law faced strong opposition from royalist groups.

Some slave owners and priests even falsified birth certificates to make newborns appear as enslaved. They also hid adult enslaved people when the government tried to conscript them into the army.

End of Congress

After the coup, relations between José Miguel Carrera and the Larraín family worsened. Joaquín Larraín boasted that his family held all the important positions. But the Carrera brothers had the military power.

To change things, the Carrera family started a new plot. Royalists, mistakenly believing the Carreras would bring back the old system, supported them. The Carreras promised to put their father, Ignacio de la Carrera, in charge of the government.

The coup happened on November 15, led by Juan José Carrera. After taking military control of the capital, he demanded that Congress and the board meet to hear "the voice of the people." The Congress president thought it was a minor event and prepared to gather the deputies. But the board tried to talk Juan José out of it, without success.

Juan José Carrera's refusal to listen to the board scared Congress. They feared a return to the old government. Though they tried to resist the demand for a public assembly, they had to agree.

The assembly, made up of about 300 people, mainly demanded changes in government staff and an end to the exiles ordered after the September 4 coup.

Congress debated these demands intensely. Juan José Carrera promised that the new institutions would be maintained, which eased the congressmen's fears. They continued discussing until late at night, deciding to resume the next day.

On November 16, the executive board resigned. New government leaders were chosen during the public assembly. The positions went to Gaspar Marín, Bernardo O'Higgins, and José Miguel Carrera, with Carrera as president. Congress could not stop Carrera's rise. However, they hoped Marín and O'Higgins would balance his power, and they convinced them to accept their roles despite their initial reluctance.

After these events, Congress continued to meet but lost most of its political power. Its sessions focused on minor topics, and minutes were no longer recorded after Manuel de Salas resigned as secretary.

To fully control the government, Carrera only needed to dissolve Congress. He delivered the final blow on December 2. That day, Congress was in session when soldiers surrounded the building with cannons pointed at it. Sentries were ordered not to let deputies leave. Congress was told to dissolve, and after some discussion, they agreed to resign.

The Congress is suspended until the provinces of the kingdom are notified. It need not be a permanent body; therefore, there is no obstacle to suspension. The legislative power is essentially incommunicable by the representatives, and can only be so by the will of those who confer it. All other powers, including those requested by the troops, remain in the executive power.

The deputies were disheartened. On December 4, Carrera issued a long statement explaining why he suspended Congress. He argued that calling a Congress was too soon, as Chile wasn't ready for full independence. He also claimed the elections were flawed, influenced by powerful people rather than the public's will. He said Congress had been inefficient and was leading the country to ruin.

From that moment on, José Miguel Carrera and his brothers had almost complete control of the government. This led to a more radical push for self-rule, which eventually resulted in Chile's independence.

Members of the First National Congress

Proprietary deputies

| District | Deputy | Political party |

|---|---|---|

| Copiapó | Juan José Echeverría | Patriot |

| Huasco | Ignacio José de Aránguiz | Moderate |

| Coquimbo | Presbyter Marcos Gallo Vergara | Monarchism |

| Manuel Antonio Recabarren | Patriot | |

| Illapel | Joaquín Gandarillas Romero | Moderate |

| Petorca | Estanislao Portales Larraín | Moderate |

| Aconcagua | José Santos Mascayano | Patriot |

| Los Andes | Francisco Ruiz-Tagle | Moderate |

| Quillota | José Antonio Ovalle y Vivar | Patriot |

| Valparaíso | Agustín Vial Santelices | Patriot |

| Santiago | Joaquín Echeverría y Larraín | Patriot |

| Count of Quinta Alegre Juan Agustín Alcalde Bascuñán | Moderate | |

| Agustín Eyzaguirre Arechavala | Moderate | |

| Francisco Javier de Errázuriz Aldunate | Monarchism | |

| José Miguel Infante | Patriot | |

| José Santiago Portales | Moderate | |

| José Nicolás de la Cerda de Santiago Concha | Moderate | |

| Juan Antonio Ovalle Silva | Moderate | |

| Fray Pedro Manuel Chaparro | Monarchism | |

| Juan José de Goycoolea | Monarchism | |

| Gabriel José Tocornal Jiménez | Moderate | |

| Domingo Díaz de Salcedo y Muñoz | Monarchism | |

| Melipilla | José de Fuenzalida y Villela | Moderate |

| Rancagua | Fernando Errázuriz Aldunate | Monarchism |

| San Fernando | José María Ugarte y Castelblanco | Monarchism |

| José María de Rozas Lima y Melo | Patriot | |

| Curicó | Martín Calvo Encalada | Moderate |

| Talca | Manuel Pérez de Cotapos y Guerrero | Monarchism |

| Mateo Vergara | Monarchism | |

| Linares | Juan Esteban Fernández del Manzano | Patriot |

| Cauquenes | Presbyter Juan Antonio Soto y Aguilar | Monarchism |

| Itata | Manuel de Salas y Corvalán | Patriot |

| Chillán | Antonio Urrutia de Mendiburu | Patriot |

| Pedro Ramón de Arriagada | Patriot | |

| Concepción | Conde La Marquina Andrés Alcázar y Díez de Navarrete | Monarchism |

| Canon Agustín Ramón Urrejola Leclerc | Monarchism | |

| Juan Cerdán Campaña | Monarchism | |

| Rere | Luis de la Cruz y Goyeneche | Patriot |

| Los Ángeles | Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme | Patriot |

| Puchacay | Juan Pablo Fretes | Patriot |

| Osorno | Manuel Fernández Hortelano | Monarchism |

Alternate Deputies

| District | Alternate Deputy |

|---|---|

| Copiapó | José Antonio Astorga |

| Huasco | José Jiménez de Guzmán |

| Coquimbo | |

| Illapel | |

| Petorca | |

| Aconcagua | |

| Los Andes | José Manuel Canto |

| Quillota | Francisco Pérez |

| Valparaíso | |

| Santiago | |

| Miguel Morales Calvo Encalada | |

| José Manuel Lecaros | |

| Lorenzo Fuenzalida Corbalán | |

| José Antonio Astorga | |

| José Agustín Jaraquemada | |

| José Antonio Rosales | |

| Benito Vargas Prado | |

| Antonio Aránguiz Mendieta | |

| Francisco Valdivieso Vargas | |

| Juan Francisco León de la Barra | |

| Manuel Valdés Valdés | |

| Francisco Antonio de la Lastra | |

| Melipilla | José Ignacio Eyzaguirre |

| Rancagua | Isidoro Errázuriz |

| San Fernando | Diego Elizondo Prado |

| Curicó | Diego Valenzuela |

| Talca | Juan de Dios Vial del Río |

| Linares | |

| Cauquenes | Fray Domingo de San Cristóbal |

| Chillán | |

| Itata | Presbyter Joaquín Larraín y Salas |

| Concepción | Luis Urrejola Leclerc |

| Francisco González Palma | |

| Manuel Rioseco | |

| Rere | Presbyter Gabriel Bachiller |

| Los Ángeles | José María Benavente |

| Puchacay | Fray Camilo Henríquez |

| Osorno | Francisco Ramón de Vicuña |

Presidents of Congress

| President | Vice President | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Juan Martínez de Rozas | July 4 | |

| Juan Antonio Ovalle | Martín Blanco Encalada | July 4 - July 20 |

| Martín Calvo Encalada | Agustín Urrejola | July 20 - August 5 |

| Manuel Pérez Cotapos | Juan Cerdán Campaña | August 5 - August 20 |

| Juan Cerdán Campaña | Agustín Eyzaguirre | August 20 - September 20 |

| Joaquín Larraín | Manuel Antonio Recabarren | September 20 - October 19 |

| Juan Pablo Fretes | José María Rozas | October 19 - November 22 |

| Joaquín Echeverría Larraín | Hipólito de Villegas | November 22 - December 2 |

Secretary of Congress

| Secretaries | Period |

|---|---|

| Francisco Ruiz-Tagle Portales (accidental secretary) | July 4 |

| José Francisco de Echaurren

Diego Antonio de Elionzo y Prado |

July 4 - July 30 |

| Diego Antonio de Elionzo y Prado

Agustín de Vial Santelices |

July 30 - August 10 |

| Agustín de Vial Santelices | August 10 - September 12 |

| Agustín de Vial Santelices

Manuel de Salas |

September 12 - November 15 |

| Preceded by Government Junta of Chile (1810) |

National Congress of Government of the Kingdom of Chile July 4, 1811 - December 2, 1811 |

Succeeded by Government Junta of Chile (August 1811) |

See also

In Spanish: Primer Congreso Nacional de Chile para niños

In Spanish: Primer Congreso Nacional de Chile para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |