History of Chile facts for kids

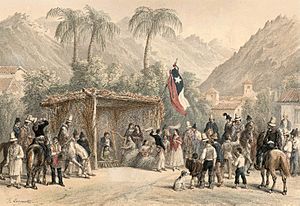

The land of Chile has been home to people for a very long time, at least since 3000 BC. By the 1500s, Spanish explorers and soldiers, called conquistadors, started to take over the area we now know as Chile. It was a Spanish colony from 1540 until 1818, when it became independent after the War of Independence.

Chile's economy grew by exporting different things. First, it was farm products, then a mineral called saltpeter, and later copper. Having lots of natural resources helped the country grow rich. But it also meant Chile depended a lot on these exports, and sometimes it even led to wars with nearby countries. For about 150 years after independence, Chile was mostly ruled by small groups of powerful people.

Later, there were growing problems with the economy and society. More people wanted a say in politics. Also, outside groups tried to influence Chile's politics, especially during the Cold War. This led to big disagreements under Socialist President Salvador Allende. These disagreements resulted in a military takeover in 1973. General Augusto Pinochet then ruled for 17 years. During this time, there were many serious problems with human rights. The economy also changed a lot, focusing more on free markets. In 1990, Chile peacefully returned to democracy and has had democratic governments ever since.

Contents

- Ancient History of Chile (Before 1540)

- European Arrival and Settlement (1540–1810)

- Chile Becomes Independent (1810–1818)

- Chile's Republican Era (1818–1891)

- Parliamentary Era (1891–1925)

- Presidential Era (1925–1973)

- Military Rule (1973–1990)

- Return to Democracy (1990–Present)

- See also

- Images for kids

Ancient History of Chile (Before 1540)

About 10,000 years ago, early Native Americans traveled and settled in the rich valleys and along the coast of what is now Chile. Before the Spanish arrived, Chile was home to many different Native American groups. Scientists think that the first people came to the Americas either by traveling quickly down the Pacific coast or even by crossing the Pacific Ocean. Evidence for this comes from the Monte Verde site, which is thousands of years older than other known early sites.

Even though there were many different groups, we can put them into three main cultural types. The northern people made beautiful crafts and were influenced by older cultures from Peru. The Araucanian culture lived between the Choapa River and Chiloé Island. They mostly farmed. The Patagonian culture included many nomadic tribes who lived by fishing and hunting.

No single, large, powerful civilization ruled all of Chile. The Araucanians were the biggest Native American group in Chile. They were hunters, gatherers, and farmers, living in small family groups and villages. They traded and sometimes fought with other groups. The Araucanians did not have a written language, but they spoke a common language. Those in central Chile were more settled and used irrigation for farming. Those in the south combined farming with hunting. The Mapuche people, meaning "people of the land," were one of the Araucanian groups. They fought fiercely against anyone trying to take their land.

The Inca Empire from Peru briefly expanded into northern Chile. They collected taxes from small groups of fishermen and farmers. But they could not establish a strong presence there. Like the Spanish after them, the Incas faced strong resistance and could not control the southern areas. In 1460 and again in 1491, the Incas built forts in Chile's Central Valley. But they could not settle the region. The Mapuche fought against the Inca ruler Tupac Inca Yupanqui and his army. After a bloody three-day battle, the Inca conquest of Chile ended at the Maule river. This river then became the border between the Inca Empire and the Mapuche lands until the Spanish arrived.

Experts believe that about 1.5 million Araucanian people lived in Chile when the Spanish arrived in the 1530s. A hundred years of European takeover and diseases cut that number by at least half. During the conquest, the Araucanians quickly learned to use horses and European weapons, adding them to their clubs and bows and arrows. They became very good at raiding Spanish settlements. They managed to keep the Spanish and their descendants away until the late 1800s. The bravery of the Araucanians inspired Chileans to see them as the nation's first heroes. However, this did not improve the difficult lives of their descendants.

The Chilean Patagonia, south of the Calle-Calle River in Valdivia, had many tribes. The main group was the Tehuelches. Spanish explorers with Magellan in 1520 thought they were giants. The name Patagonia comes from the word patagón, which Magellan used to describe these native people. It is now believed the Tehuelches were about 1.80 meters (5 feet 11 inches) tall. This was taller than the average Spaniard of that time, who was about 1.55 meters (5 feet 1 inch).

European Arrival and Settlement (1540–1810)

The first European to see Chilean land was Ferdinand Magellan in 1520. He sailed through the Strait of Magellan. However, Diego de Almagro is usually called the "discoverer of Chile." Almagro was a partner of Francisco Pizarro, who conquered Peru. Almagro led an expedition to central Chile in 1537. But he found little gold or silver compared to what the Incas had in Peru. Thinking the people there were poor, he went back to Peru.

After Almagro's trip, Spanish leaders were not very interested in exploring Chile further. But Pedro de Valdivia, a Spanish army captain, saw that the Spanish empire could grow southward. He asked Pizarro for permission to invade and conquer these southern lands. With a few hundred men, he defeated the local people. He founded the city of Santiago de Nueva Extremadura, now Santiago de Chile, on February 12, 1541.

Valdivia found little gold in Chile, but he saw that the land was rich for farming. He continued exploring west of the Andes mountains. He founded more than a dozen towns and set up the first encomiendas, which were systems of forced labor for Native Americans. The strongest resistance to Spanish rule came from the Mapuche people. They fought against European conquest until the 1880s. This long fight is known as the Arauco War. Valdivia died in the Battle of Tucapel, defeated by Lautaro, a young Mapuche war chief. But the European takeover was already well underway.

The Spanish never fully controlled the Mapuche lands. Many attempts to conquer them, both by fighting and by peaceful talks, failed. A big uprising in 1598 pushed all Spanish presence south of the Bío-Bío River away, except for Chiloé. The Bío-Bío River then became the border between Mapuche lands and the Spanish areas. North of this river, cities grew slowly. Chilean lands eventually became an important source of food for the Spanish colony in Peru.

Valdivia became the first governor of the Captaincy General of Chile. He reported to the viceroy of Peru, who in turn reported to the King of Spain. Local towns were managed by councils called Cabildos. Santiago was the most important town and had a Royal Appeals Court from 1609 until the end of Spanish rule. For most of its colonial history, Chile was the least wealthy part of the Spanish Empire. Only in the 1700s did the economy and population start to grow steadily. This was due to reforms by Spain's Bourbon kings and a more stable situation along the border.

Chile Becomes Independent (1810–1818)

The push for independence from Spain began when Napoleon's brother took over the Spanish throne. Chile's War of Independence was part of a bigger movement across Spanish America. Not all Chileans supported independence; some wanted to stay loyal to Spain. What started as a political movement by the wealthy against their colonial rulers turned into a civil war. People who wanted independence, called Criollos, fought against royalist Criollos who supported Spain. This was a war within the upper class, but most soldiers on both sides were ordinary people.

The independence movement officially began on September 18, 1810. On that day, a national council was formed to govern Chile in the name of the Spanish king, who had been removed from power. The movement lasted until 1821, when the Spanish were driven from mainland Chile. Or, some say it lasted until 1826, when the last Spanish troops surrendered. The independence process is usually divided into three parts: Patria Vieja (Old Homeland), Reconquista (Reconquest), and Patria Nueva (New Homeland).

Chile's first attempt at self-rule, the "Patria Vieja" (1810–1814), was led by José Miguel Carrera. He was a young aristocrat and a military man. Carrera ruled with a strong hand, which made many people oppose him. Another early supporter of full independence, Bernardo O'Higgins, led a rival group. This caused a civil war among the Criollos. For O'Higgins and some others, temporary self-rule quickly became a fight for complete independence. But other Criollos stayed loyal to Spain.

Among those who wanted independence, conservatives and liberals argued about how much to use ideas from the French Revolution. After several attempts, Spanish troops from Peru took advantage of the fighting among Chileans. They reconquered Chile in 1814, taking back control after the Battle of Rancagua on October 12. O'Higgins, Carrera, and many other Chilean rebels escaped to Argentina.

The second period was the "Reconquista" (1814–1817). During this time, the Spanish loyalists ruled harshly and punished suspected rebels. This pushed more and more Chileans to join the independence movement. More members of Chile's elite became convinced that full independence was necessary. Manuel Rodríguez Erdoíza became a national symbol of resistance by leading guerrilla attacks against the Spanish.

In Argentina, O'Higgins joined forces with José de San Martín. Their combined army freed Chile with a daring crossing of the Andes mountains in 1817. They defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Chacabuco on February 12, which marked the start of the Patria Nueva. San Martín believed that freeing Chile was an important step to freeing Peru, which he saw as key to defeating the Spanish in the whole region.

Chile officially won its independence when San Martín defeated the last large Spanish force on Chilean soil at the Battle of Maipú on April 5, 1818. San Martín then led his Argentine and Chilean followers north to free Peru. Fighting continued in Chile's southern provinces, where many royalists were, until 1826. Chile officially declared its independence on February 12, 1818. Spain formally recognized Chile's independence in 1840.

Chile's Republican Era (1818–1891)

Building a New Government (1818–1833)

From 1817 to 1823, Bernardo O'Higgins ruled Chile as its supreme director. He was praised for defeating the royalists and starting schools. But civil unrest continued. O'Higgins upset liberals and people from the provinces because he was too strict. He angered conservatives and the church because he tried to reduce the church's power. He also upset landowners with his ideas for changing land ownership. His attempt to create a constitution in 1818 to make his government legal failed. He also struggled to find stable money for the new government. O'Higgins's strong rule led to resistance in the provinces. This growing unhappiness was also seen in the continued opposition from supporters of José Miguel Carrera.

Although many liberals opposed him, O'Higgins also angered the Roman Catholic Church with his liberal beliefs. He kept Catholicism as the official state religion. But he tried to limit the church's political power and encourage religious tolerance. This was to attract Protestant immigrants and traders. Like the church, the wealthy landowners felt threatened by O'Higgins. They disliked his attempts to get rid of noble titles and, more importantly, to end inherited estates.

O'Higgins's opponents also did not like that he used Chile's resources to help San Martín free Peru. O'Higgins insisted on supporting that campaign because he knew that Chile's independence would not be safe until the Spanish were defeated in Peru. However, with growing unhappiness, troops from the northern and southern provinces forced O'Higgins to resign. Upset, O'Higgins left for Peru, where he died in 1842.

After O'Higgins left in 1823, civil conflict continued. The main issues were about the church's power and regional differences. Presidents and constitutions changed quickly in the 1820s. The civil struggle hurt the economy, especially exports. This led conservatives to take control in 1830. Most of Chile's elite believed that the fighting and chaos of the late 1820s were due to the problems with liberalism and federalism. These ideas had been strong for most of that time. The political groups were divided. There were supporters of Bernardo O'Higgins and José Miguel Carrera. There were also liberal Pipiolos and conservative Pelucones. These last two became the main groups. One of the few lasting achievements of the Pipiolos was ending slavery in 1823, long before many other countries in the Americas. A Pipiolo leader from the south, Ramón Freire, was president several times but could not keep his authority.

In August 1828, Chile changed from a short-lived federal system to a single, unified government. It had separate legislative, executive, and judicial branches. By adopting a moderately liberal constitution in 1828, President Pinto upset both the federalists and the liberal groups. He also angered the old wealthy families by ending inherited estates. He caused public outrage with his anti-church views. After his liberal army was defeated at the Battle of Lircay on April 17, 1830, Freire, like O'Higgins, went into exile in Peru.

Conservative Rule (1830–1861)

Even though he was never president, Diego Portales greatly influenced Chilean politics from 1830 to 1837. He set up an "autocratic republic," which meant power was held strongly by the national government. His political plan was supported by merchants, large landowners, foreign investors, the church, and the military. Political and economic stability helped each other. Portales encouraged economic growth through free trade and fixed government finances. Portales believed the Roman Catholic Church was very important for loyalty, order, and stability, just as it had been during colonial times. He canceled liberal reforms that had threatened the church's special rights and properties.

The "Portalian State" was made official by the Chilean Constitution of 1833. This was one of the most lasting constitutions in Latin America, staying in place until 1925. The constitution gave a lot of power to the national government, especially to the president. The president was chosen by a very small group of voters. The president could serve two five-year terms in a row and then choose a successor. Even though Congress had important power over money, the president was more powerful and appointed officials in the provinces. The constitution also created an independent court system, guaranteed inherited estates, and made Catholicism the state religion. In short, it set up a strong, centralized system that looked like a republic.

Portales also achieved his goals by using strong powers, controlling the press, and influencing elections. For the next forty years, Chile's military was kept busy with small fights and defense operations on the southern border.

The first Portalian president was General Joaquín Prieto, who served two terms (1831–1841). President Prieto had four main achievements: putting the 1833 constitution into action, stabilizing government money, defeating challenges to central authority from the provinces, and winning against the Peru-Bolivia Confederation. During Prieto's presidencies and those of his two successors, Chile modernized. They built ports, railroads, and telegraph lines, some with the help of American businessman William Wheelwright. These improvements helped both international trade and business within the country.

Prieto and Portales were worried about the efforts of Bolivian general Andrés de Santa Cruz to unite with Peru against Chile. These worries made old dislikes towards Peru worse. Chile also wanted to be the strongest military and trade power on the Pacific coast of South America. Santa Cruz united Peru and Bolivia in the Peru–Bolivian Confederation in 1836. He wanted to expand control over Argentina and Chile. Portales convinced Congress to declare war on the Confederation. Portales was killed by traitors in 1837. General Manuel Bulnes defeated the Confederation in the Battle of Yungay in 1839.

After his victory, Bulnes was elected president in 1841. He served two terms (1841–1851). His government focused on settling new territories, especially the Strait of Magellan and the Araucanía. The Venezuelan scholar Andrés Bello made important intellectual progress during this time, most notably creating the University of Santiago. But political tensions, including a liberal rebellion, led to the Chilean Civil War of 1851. In the end, the conservatives defeated the liberals.

The last conservative president was Manuel Montt, who also served two terms (1851–1861). But his poor leadership led to a liberal rebellion in 1859. Liberals won in 1861 with the election of José Joaquín Perez as president.

Liberal Rule (1861–1891)

The political changes brought little social change. Chilean society in the 1800s kept its old social structure, which was heavily influenced by family politics and the Roman Catholic Church. A strong presidency eventually developed, but wealthy landowners remained powerful.

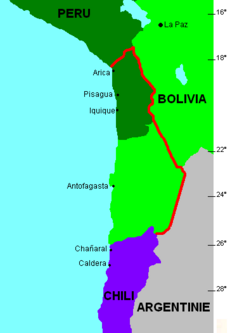

Towards the end of the 1800s, the government in Santiago strengthened its control in the south. It did this by continuously putting down the Mapuche during the Occupation of the Araucanía. In 1881, Chile signed a treaty with Argentina. This treaty confirmed Chile's control over the Strait of Magellan. But it gave up a large part of eastern Patagonia, which Chile had claimed during colonial times. As a result of the War of the Pacific with Peru and Bolivia (1879–1883), Chile gained territory to the north. This new land had valuable nitrate deposits. Using these deposits led to a time of national wealth.

In the 1870s, the church's influence began to lessen slightly. Several laws were passed that gave some of the church's old roles to the state, such as keeping records of births and marriages.

In 1886, José Manuel Balmaceda was elected president. His economic policies were different from the existing liberal ones. He started to act against the constitution and slowly began to set up a dictatorship. Congress decided to remove Balmaceda, but he refused to step down. Jorge Montt, among others, led an armed conflict against Balmaceda. This soon grew into the 1891 Chilean Civil War. Defeated, Balmaceda fled to Argentina's embassy. Jorge Montt became the new president.

Parliamentary Era (1891–1925)

The period called the Parliamentary Republic was not a true parliamentary system. In a true system, the leader is chosen by the lawmakers. However, it was unusual for Latin America, where presidents usually had more power. In Chile, Congress really did have more power than the president, who had a more ceremonial role. Congress also controlled who the president appointed to his cabinet. In turn, wealthy landowners controlled Congress. This was a time of classic political and economic liberalism.

For many years, historians criticized the Parliamentary Republic. They said it was a system full of arguments that only shared out rewards. They also said it stuck to its "hands-off" economic policy while national problems grew. A famous quote from President Ramón Barros Luco (1910–1915) shows this view. He supposedly said about labor unrest: "There are only two kinds of problems: those that solve themselves and those that can't be solved."

Because they depended on Congress, cabinets changed often. However, public administration was more stable than some historians have suggested. Chile also temporarily solved its border disagreements with Argentina. This happened with the Puna de Atacama Lawsuit of 1899, the Boundary treaty of 1881 between Chile and Argentina, and the 1902 General Treaty of Arbitration. But before this, there was an expensive naval arms race between the two countries.

Political power flowed from local election bosses in the provinces up through Congress and the executive branch. These branches gave back favors using money from nitrate sales. Congressmen often won elections by bribing voters in this system, which was based on favors and was corrupt. Many politicians relied on intimidated or loyal peasant voters in the countryside, even though more people were moving to cities. The uninspiring presidents and ineffective governments of this time did little to address Chile's dependence on unstable nitrate exports, rising inflation, and rapid growth of cities.

In recent years, however, especially when thinking about the later rule of Augusto Pinochet, some experts have looked at the Parliamentary Republic (1891–1925) differently. While admitting its problems, they have praised its democratic stability. They have also highlighted its control over the military, its respect for civil liberties, its expansion of voting rights, and its gradual acceptance of new groups into politics, especially reformers. Two young parties became more important: the Democrat Party, which had roots among city workers, and the Radical Party, representing middle-class city dwellers and provincial elites.

By the early 1900s, both parties were winning more and more seats in Congress. The more left-leaning members of the Democrat Party became leaders in labor unions. They broke away to start the Socialist Workers' Party (POS) in 1912. The founder of the POS and its most famous leader, Luis Emilio Recabarren, also founded the Communist Party of Chile (PCCh) in 1922.

Presidential Era (1925–1973)

By the 1920s, the growing middle and working classes were strong enough to elect a reformist president, Arturo Alessandri Palma. Alessandri appealed to those who believed social problems should be fixed. He also appealed to those worried by the drop in nitrate exports during World War I. And he appealed to those tired of presidents being controlled by Congress. Promising "evolution to avoid revolution," he started a new way of campaigning. He spoke directly to large crowds with exciting speeches and charm. After winning a Senate seat in 1915, he was called the "Lion of Tarapacá."

As a Liberal who disagreed with his party, Alessandri gained support from more reform-minded Radicals and Democrats. He formed the "Liberal Alliance." He received strong backing from the middle and working classes, as well as from wealthy families in the provinces. Students and thinkers also supported him. At the same time, he assured landowners that social reforms would only happen in cities.

Alessandri soon found that Congress would block his efforts to lead. Like Balmaceda, he angered lawmakers by appealing directly to voters in the 1924 congressional elections. His reform laws were finally passed under pressure from younger military officers. These officers were tired of the military being ignored, political arguments, social unrest, and rapid inflation.

A double military takeover started a time of great political instability that lasted until 1932. First, right-wing military officers who opposed Alessandri took power in September 1924. Then, reformers who supported the ousted president took charge in January 1925. The "saber noise" incident in September 1924, caused by unhappy young officers, led to Alessandri's exile.

However, fears of conservatives returning to power led to another takeover in January. This ended with a temporary government while waiting for Alessandri's return. This group was led by two colonels, Carlos Ibáñez del Campo and Marmaduke Grove. They brought Alessandri back to the presidency that March. He then put his promised reforms into law by decree. Alessandri took power again in March. A new Constitution with his reforms was approved by a public vote in September 1925.

The new constitution gave more power to the president. Alessandri moved away from the old "hands-off" economic policies. He created a Central Bank and put in place an income tax. However, social unrest was also put down.

The longest-lasting of the ten governments between 1924 and 1932 was that of General Carlos Ibáñez. He briefly held power in 1925 and then again from 1927 to 1931. This was a kind of dictatorship. When constitutional rule returned in 1932, a strong middle-class party, the Radicals, appeared. It became the main force in coalition governments for the next 20 years.

During the time the Radical Party was dominant (1932–1952), the government took a bigger role in the economy. In 1952, voters elected Ibáñez to office again for another 6 years. Jorge Alessandri followed Ibáñez in 1958.

The 1964 election of Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei Montalva by a clear majority started a time of big reforms. Under the slogan "Revolution in Liberty," Frei's government began wide-ranging social and economic programs. These were especially in education, housing, and land reform, including allowing farm workers to form unions. By 1967, however, Frei faced growing opposition. Leftists said his reforms were not enough, and conservatives found them too much. By the end of his term, Frei had achieved many important goals, but he had not fully met his party's big aims.

Allende's Time in Office

In the 1970 presidential election, Senator Salvador Allende Gossens won the most votes in a three-way race. He was a doctor and a member of Chile's Socialist Party. He led the "Popular Unity" (UP) group, which included Socialist, Communist, and other parties.

Allende had two main opponents: Radomiro Tomic from the Christian Democratic party, who also ran a left-leaning campaign, and former president Jorge Alessandri from the right. Allende received 36% of the votes, Alessandri 35%, and Tomic 28%.

Even though the United States government put pressure on Chile, the Chilean Congress followed tradition. They held a runoff vote between Allende and Alessandri, the top two candidates. This vote was usually just a formality, but in 1970, it was very tense. After Allende promised to follow the law, he was chosen by a vote of 153 to 35.

The Popular Unity plan included taking control of U.S. interests in Chile's major copper mines. It also aimed to improve workers' rights, expand Chilean land reform, and organize the economy into state-owned, mixed, and private parts. Its foreign policy focused on "international friendship" and national independence. It also wanted a new government system, including a single-chamber congress. Right after the election, the United States showed its disapproval and placed economic restrictions on Chile.

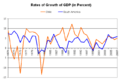

In Allende's first year, the economy showed good short-term results. Industrial growth was 12%, and the country's total economic output (GDP) increased by 8.6%. Inflation went down, and unemployment fell. Allende's government froze prices, increased wages, and reformed taxes. This helped people spend more and spread income more evenly. Public and private projects helped reduce unemployment. Many banks were taken over by the state. Many companies in the copper, coal, iron, nitrate, and steel industries were also taken over by the state or put under state control. Factory output increased sharply, and unemployment fell. However, these good results did not last. By 1972, Chile's currency had very high inflation, reaching 140%. An economic downturn that started in 1967 got worse in 1972. This was made worse by money leaving the country, falling private investment, and people taking money out of banks because of Allende's socialist plans. Production fell, and unemployment rose. The combination of inflation and government price controls led to illegal markets for basic goods like rice, beans, sugar, and flour. These items also became hard to find in stores.

The United States government tried to make Chile's economy struggle. International financial pressure limited economic loans to Chile. At the same time, outside groups funded opposition media, politicians, and organizations. This helped speed up a campaign to cause problems within the country. By 1972, the economic progress of Allende's first year had been reversed, and the economy was in crisis. Political disagreements grew, and large groups of both government supporters and opponents often gathered, sometimes leading to clashes.

By 1973, Chilean society was very divided between strong opponents and strong supporters of Salvador Allende and his government. Military actions and movements, separate from the civilian government, began to appear in the countryside. A failed military takeover attempt happened against Allende in June 1973.

On August 22, 1973, the Chamber of Deputies of Chile stated that Chilean democracy had broken down. They called for "redirecting government activity" to bring back constitutional rule. Less than a month later, on September 11, 1973, the Chilean military removed Allende from power. Allende took his own life to avoid capture as the Presidential Palace was surrounded and bombed. After this, instead of giving power back to the civilian lawmakers, Augusto Pinochet used his role as army commander to take complete control. He set himself up as the head of a military government.

Military Rule (1973–1990)

By early 1973, inflation had risen sharply under Allende's presidency. The struggling economy was further hurt by long and sometimes simultaneous strikes by doctors, teachers, students, truck owners, copper workers, and small business owners. A military takeover overthrew Allende on September 11, 1973. As the armed forces bombed the presidential palace, Allende died. A military government, led by General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, took control of the country.

The first years of this government were marked by serious human rights problems. The military government jailed and executed thousands of Chileans. In October 1973, at least 72 people were killed by a group called the "Caravan of Death." At least a thousand people were executed during Pinochet's first six months in office. At least two thousand more were killed over the next sixteen years, according to a report. At least 29,000 people were imprisoned and tortured. About 30,000 people left the country.

The four-man military government led by General Augusto Pinochet ended civil liberties. It dissolved the national congress, banned union activities, stopped strikes and group bargaining, and reversed the land and economic reforms of the Allende government.

The military government began a major program of making the economy more open and private. They cut taxes on imports and reduced government welfare programs and spending deficits. Economic changes were planned by a group of experts known as the Chicago Boys. Many of them had been trained or influenced by professors from the University of Chicago. Under these new policies, the rate of inflation dropped.

A new constitution was approved by a public vote on September 11, 1980. General Pinochet became president for an 8-year term.

In 1982–1983, Chile faced a severe economic crisis. Unemployment rose sharply, and the financial sector struggled. Many financial institutions faced bankruptcy. In 1982, the two biggest banks were taken over by the state to prevent an even worse credit shortage. In 1983, five more banks were taken over by the state, and two banks had to be supervised by the government. The central bank took over foreign debts.

After the economic crisis, Hernán Büchi became Minister of Finance from 1985 to 1989. He brought in more practical economic policies. He allowed the currency to change freely and put back limits on money moving in and out of the country. He introduced rules for banks and simplified and reduced corporate taxes. Chile continued with privatizations, including public services. It also re-privatized companies that had returned to government control during the 1982–1983 crisis. From 1984 to 1990, Chile's total economic output grew by an average of 5.9% each year, the fastest on the continent. Chile developed a good export economy, including sending fruits and vegetables to the northern hemisphere when they were out of season, which earned high prices.

The military government began to change in the late 1970s. Due to problems with Pinochet, Leigh was removed from the government in 1978 and replaced by General Fernando Matthei. In the late 1980s, the government slowly allowed more freedom for people to gather, speak, and form groups, including trade unions and political parties.

Chile's constitution stated that in 1988, there would be another public vote. Voters would either accept or reject a single candidate proposed by the military government. Pinochet was, as expected, the proposed candidate. But he was denied a second 8-year term by 54.5% of the vote.

Return to Democracy (1990–Present)

Aylwin, Frei, and Lagos Presidencies

Chileans elected a new president and most members of a two-chamber congress on December 14, 1989. Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin, the candidate of a group of 17 political parties called the Concertación, received 55% of the votes. President Aylwin served from 1990 to 1994. This was seen as a time of transition. In February 1991, Aylwin created the National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation. This commission released a report in February 1991 on human rights problems during military rule.

This report documented 2,279 cases of "disappearances" that could be proven and recorded. Of course, the nature of "disappearances" made such investigations very difficult. A similar problem arose years later with another report in 2004. This report documented almost 30,000 victims of torture, based on testimonies from 35,000 people.

In December 1993, Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle, the son of former president Eduardo Frei Montalva, led the Concertación group to victory with 58% of the votes. Frei Ruiz-Tagle was followed in 2000 by Socialist Ricardo Lagos. Lagos won the presidency in a very close runoff election against Joaquín Lavín from the right-wing Alliance for Chile. Lagos won by less than 200,000 votes (51.32%).

In 1998, Pinochet traveled to London for back surgery. But a Spanish judge ordered his arrest there. This gained worldwide attention, not just because of Chile's history, but also because it was one of the first times a former president was arrested based on the idea of "universal jurisdiction." Pinochet tried to defend himself by referring to a law about state immunity. However, the British justice system rejected this argument. Still, the British Home Secretary decided to release him for medical reasons and refused to send him to Spain. After that, Pinochet returned to Chile in March 2000. When he got off the plane in his wheelchair, he stood up and saluted the cheering crowd of supporters. President Ricardo Lagos later said that the retired general's televised arrival had hurt Chile's image, while thousands protested against him.

Bachelet and Piñera Presidencies

The Concertación group continued to be strong in Chilean politics for the next two decades. In January 2006, Chileans elected their first female president, Michelle Bachelet, from the Socialist Party. She took office on March 11, 2006, extending the Concertación group's rule for another four years.

In 2002, Chile signed an agreement with the European Union (including free trade and cultural agreements). In 2003, it signed a big free trade agreement with the United States, and in 2004, with South Korea. Chile hoped for a big increase in imports and exports and to become a regional trade center. Continuing the group's free trade plan, in August 2006, President Bachelet made a free trade agreement with China official. This was the first Chinese free trade agreement with a Latin American country. Similar deals with Japan and India were made official in August 2007. In October 2006, Bachelet made official a trade deal with New Zealand, Singapore, and Brunei. Regionally, she signed free trade agreements with Panama, Peru, and Colombia.

After 20 years, Chile went in a new direction with the win of center-right Sebastián Piñera. He won the Chilean presidential election of 2009–2010, defeating former President Eduardo Frei in the runoff vote.

On February 27, 2010, Chile was hit by a very strong 8.8 magnitude earthquake. It was one of the largest ever recorded at the time. More than 500 people died, mostly from the tsunami that followed. Over a million people lost their homes. The earthquake was also followed by many aftershocks. Early estimates of the damage were between US$15–30 billion, which was about 10 to 15 percent of Chile's total economic output.

Chile gained global recognition for the successful rescue of 33 trapped miners in 2010. On August 5, 2010, the access tunnel collapsed at the San José copper and gold mine in the Atacama Desert. This trapped 33 men 700 meters (about 2,300 feet) underground. The Chilean government organized a rescue effort and found the miners 17 days later. All 33 men were brought to the surface two months later, on October 13, 2010. This effort took almost 24 hours and was shown live on television around the world.

Despite good economic numbers, there was growing social unhappiness. People demanded better and fairer education. This led to massive protests calling for more democratic and fair institutions. Support for Piñera's government fell greatly.

In 2013, Bachelet, a Social Democrat, was elected president again. She aimed to make the big changes society had been asking for in recent years. These included education reform, tax reform, and allowing same-sex civil unions. She also wanted to end the old political system, aiming for more equality and to remove what remained from the dictatorship. In 2015, several corruption scandals became public, hurting the trust in politicians and business leaders.

On December 17, 2017, Sebastián Piñera was elected president of Chile for a second term. He received 36% of the votes, the highest among all 8 candidates. In the second round, Piñera faced Alejandro Guillier, a TV news anchor who represented Bachelet's New Majority group. Piñera won the elections with 54% of the votes.

Social Unrest and New Constitution Efforts

In October 2019, there were violent protests about the cost of living and inequality. This led Piñera to declare a state of emergency. On November 15, most political parties in the National Congress signed an agreement. They decided to call a national vote in April 2020 about creating a new Constitution. But the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the election date. On October 25, 2020, Chileans voted 78.28% in favor of a new constitution, while 21.72% rejected the change. Voter turnout was 51%. A second vote was held on April 11, 2021, to choose 155 Chileans to form the group that would write the new constitution.

On December 19, 2021, leftist candidate Gabriel Boric, a 35-year-old former student protest leader, won Chile's presidential election. He became the country's youngest leader after a very divided election. He defeated right-wing candidate José Antonio Kast. The center-left and center-right political groups that had shared power for the last 32 years ended up in fourth and fifth place in the presidential election.

Gabriel Boric's Presidency (2022- )

On March 11, 2022, Gabriel Boric was sworn in as president, taking over from outgoing President Sebastian Piñera. Out of 24 members of Gabriel Boric's cabinet, 14 are women, making it a female-majority cabinet.

On September 4, 2022, voters strongly rejected the new constitution in a public vote. This constitution had been proposed by the constitutional convention and strongly supported by President Boric. Before the proposed constitution was rejected, polls showed that the idea of "plurinationalism" (recognizing multiple nations within Chile) was particularly divisive.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Chile para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Chile para niños

- Arauco War

- Chincha Islands War

- COVID-19 pandemic in Chile

- Economic history of Chile

- List of presidents of Chile

- Miracle of Chile

- Occupation of the Araucanía

- Politics of Chile

- Timeline of Chilean history

- U.S. intervention in Chile

- War of the Confederation

- War of the Pacific

General:

- History of the Americas

- History of Latin America

- History of South America

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

Images for kids