Shinkansen facts for kids

The Shinkansen (新幹線), known around the world as the bullet train, is Japan's network of high-speed railway lines. The name Shinkansen means "new trunk line" in Japanese. These amazing trains connect major cities across the country, helping Japan's economy grow.

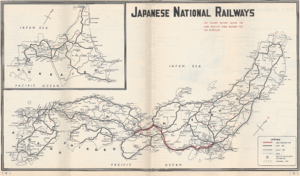

The first Shinkansen line, the Tokaido Shinkansen, opened in 1964. It connected the cities of Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka. Since then, the network has grown to cover most of the main islands of Honshu and Kyushu. It even reaches the northern island of Hokkaido.

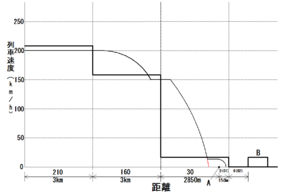

Shinkansen trains are famous for their speed, safety, and for almost always being on time. They can travel at speeds between 260 and 320 km/h (160-200 mph). Test trains have gone even faster, with a special magnetic levitation (maglev) train setting a world record of 603 km/h (375 mph) in 2015!

The original Tokaido Shinkansen line is one of the busiest high-speed railways in the world. It carries millions of passengers every year. During the busiest times, up to 16 trains per hour travel in each direction. Each train can have 16 cars and hold over 1,300 people.

Contents

The Story of the Shinkansen

Japan was the first country in the world to build special railway lines just for high-speed travel. Before the Shinkansen, Japan's trains ran on narrow tracks. These tracks had many curves because of the country's mountains, which meant trains couldn't go very fast. A new, straighter railway with wider tracks was needed for high-speed travel.

Early Ideas

The idea for a "bullet train" started back in the 1930s. The name came from the train's rounded nose, which looked like a bullet, and its incredible speed. Early plans were put on hold because of World War II.

After the war, Japan's economy grew quickly. The main train line between Tokyo and Osaka, the Tōkaidō Main Line, became too crowded. By the mid-1950s, it was clear that a new solution was needed. The government decided to bring back the Shinkansen project.

Building the First Line

Construction on the Tōkaidō Shinkansen began in 1959. It was a huge project that cost a lot of money. The government, along with the World Bank, helped pay for it.

The first Shinkansen line opened on October 1, 1964, just in time for the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. It was a huge success! The trip from Tokyo to Osaka, which used to take almost seven hours, was cut to just four hours. This made it possible for people to take day trips between Japan's two largest cities.

The Network Grows

Because the first line was so successful, more lines were built. The network expanded west to cities like Hiroshima and Fukuoka. Later, lines were built north from Tokyo, connecting more of the country.

Today, the Shinkansen network is run by several private companies that are part of the Japan Railways Group. They continue to develop new and faster trains, keeping the Shinkansen at the cutting edge of railway technology.

Amazing Shinkansen Technology

The Shinkansen uses special technology to travel safely at high speeds. Its success has inspired other countries to build their own high-speed rail networks.

Tracks and Tunnels

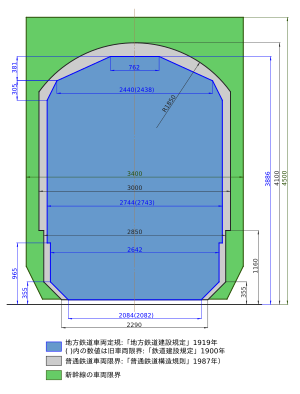

Shinkansen tracks are a different size (standard gauge) than most other train tracks in Japan (narrow gauge). This means Shinkansen trains have their own dedicated lines and don't have to share with slower local trains. The tracks are welded together to create a smooth, continuous rail, which makes the ride comfortable even at high speeds.

The routes are very straight, often using tunnels to go through mountains and viaducts (long bridges) to go over valleys. This avoids sharp curves that would force the train to slow down.

Smart Signal System

Shinkansen trains don't use traditional trackside signals. Instead, they have an Automatic Train Control (ATC) system. This system is built into the train and the track. It automatically controls the train's speed and can apply the brakes if needed, making it very safe. All train movements are managed by a central command center.

Powerful Electric Trains

Shinkansen trains are electric multiple units (EMUs). This means that instead of having one engine pulling the cars, many of the cars have their own electric motors. This allows the train to accelerate and decelerate very quickly.

The train cars are also wider than regular Japanese trains. This allows for more spacious seating, usually with five seats across (3 on one side, 2 on the other) in Standard Class.

Shinkansen Lines and Services

The Shinkansen network is made up of several main lines that connect Japan's biggest cities.

Main Lines

- Tokaido Shinkansen: The original line, connecting Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka.

- San'yō Shinkansen: Continues from Osaka to Fukuoka.

- Tōhoku Shinkansen: The longest line, running from Tokyo north to Aomori.

- Jōetsu Shinkansen: Runs from the Tokyo area to Niigata.

- Hokuriku Shinkansen: Connects Tokyo with Kanazawa and Tsuruga on the coast of the Sea of Japan.

- Kyushu Shinkansen: Runs on the southern island of Kyushu.

- Hokkaido Shinkansen: Connects Aomori to Hakodate on the northern island of Hokkaido.

There are also two Mini-shinkansen lines, the Yamagata Shinkansen and Akita Shinkansen. These lines use upgraded conventional tracks, allowing Shinkansen trains to reach cities that are not on the main high-speed network.

Types of Services

On most lines, there are three types of train services:

- Express: The fastest service, stopping only at the biggest stations.

- Semi-express: Stops at major stations and some smaller ones.

- Local: Stops at every station on the line.

Each service has a unique name. For example, on the Tokaido line, the fastest train is the Nozomi, the semi-express is the Hikari, and the local is the Kodama.

Meet the Shinkansen Trains

Over the years, many different models of Shinkansen trains have been built. Each new series is faster, more comfortable, and more efficient than the last.

Famous Shinkansen Models

- 0 Series: The original "bullet train" from 1964. It was used for over 40 years before being retired in 2008.

- 500 Series: Known for its futuristic, jet-fighter-like design. It was the first train in Japan to operate at 300 km/h (186 mph).

- 700 Series: Famous for its unique "duck-bill" nose, designed to reduce noise when entering tunnels.

- N700 Series: A modern and very common train. An advanced version, the N700S, is one of the newest trains on the network.

- E5 / H5 Series: Used on the Tohoku and Hokkaido lines. These trains have a very long nose and can travel at 320 km/h (200 mph).

- E6 Series: A "mini-shinkansen" train used on the Akita line, famous for its bright red color.

- E7 / W7 Series: A stylish blue and copper train used on the Hokuriku Shinkansen.

Safety and Punctuality

The Shinkansen is famous for being incredibly safe and reliable.

- Safety Record: In over 60 years of operation, carrying billions of passengers, there has never been a passenger death caused by a derailment or collision. This amazing record is thanks to the advanced technology and strict safety rules.

- Earthquake Protection: Japan experiences many earthquakes. The Shinkansen has a special system that detects earthquakes and automatically stops the trains before the strongest shaking arrives.

- Punctuality: The trains are almost never late. In 2016, the average delay for a Shinkansen train was just 24 seconds! The system shuts down every night between midnight and 6:00 AM for maintenance to keep everything running perfectly.

The Future of the Shinkansen

Japan continues to improve and expand its high-speed rail network.

Faster Speeds

Engineers are always working on ways to make the trains faster. The new ALFA-X test train is being used to research technology for future Shinkansen that could travel at 360 km/h (224 mph).

New Lines

- Hokkaido Shinkansen: This line is being extended from Hakodate to Sapporo, the largest city in Hokkaido.

- Chūō Shinkansen: This is a brand-new line being built between Tokyo and Nagoya, and later to Osaka. It will use maglev (magnetic levitation) technology, which allows the train to float above the track. These trains will travel at over 500 km/h (310 mph), cutting the travel time between Tokyo and Nagoya to just 40 minutes.

Shinkansen Around the World

Shinkansen technology has been so successful that other places have adopted it.

- Taiwan: The Taiwan High Speed Rail uses trains based on the Japanese 700 Series Shinkansen.

- China: Some of China's early high-speed trains were based on the E2 Series Shinkansen.

- United Kingdom: The British Rail Class 395 trains, which run on a high-speed line in England, use Shinkansen technology.

- India: A new high-speed line is being built between Mumbai and Ahmedabad using Japan's E5 Series Shinkansen technology.

- United States: A private company plans to build a high-speed line in Texas using the N700 series train.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Shinkansen para niños

In Spanish: Shinkansen para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |